Today’s Los Angeles Times has a big take-out by Joe Mozingo, with photos by Francine Orr and extensive online graphics, about the ongoing woes of San Bernardino, California. The city’s problems, as we’ve set out in previous installments, have been a heartbreaking vicious-cycle combination of economic misfortune worsened by political dysfunction. Over the past generation, San Bernardino has lost every one of its traditional big sources of blue-collar employment: a steel mill, a railroad yard, the commerce related to a major Interstate (before it was relocated 15 miles west), and then an enormous Air Force base.

We’ve been to other cities that have endured nearly comparable business-loss blows and have found ways to adapt and recover. What made San Bernardino’s problems so much worse was its uniquely paralyzed form of city government, which had a classic “failed-state” effect.

As the city’s people grew poorer, their dwindling resources were increasingly funneled to a small class of politically favored interest groups. In San Bernardino’s case, those were mainly the police and fire-fighter unions—nearly all of whose members lived in other, “nicer” cities and who became among the best-paid public employees in the state even as the city was becoming the most impoverished. The L.A. Times piece points out that as median household income in the city was sinking below $40,000, median pay for firefighters was rising above $150,000.

I’ll leave the structural problems there for the moment. For more, please do read the L.A. Times feature, which includes accounts of many of the city’s left-behinds; or follow the city-in-crisis reporting of Ryan Hagen in the San Bernardino Sun; or see the city’s official Plan of Adjustment for pulling itself out of bankruptcy; or see the 2014 analysis by the consulting firm Management Partners about the roots of the city’s problems and an earlier Vision Statement, or this analysis from George Mason University. Plus our articles “What It’s Like When Your City Goes Broke,” “Today a Bankrupt City Votes on Its Next Steps,” “Steps in Civic Life,” and the first half of this post, on why the real divide in California is not north versus south but rather coastal California versus the inland areas.

I mentioned several posts ago that San Bernardino’s problems are so well chronicled that from this point on we’re going to focus on people who are trying to do something about them. Thus we’ve told the stories of “Generation Now,” a young-people’s organization trying to make San Bernardino’s residents feel like citizens; the AVID program at a local which school, which “saves lives one at a time“; crusading former mayor Pat Morris; and current school board president Mike Gallo, an aerospace entrepreneur who now dedicates his considerable energies to improving life prospects for the mainly poor, mainly non-white students in his adopted city’s public schools.

Today’s installment: a look at Dr. Bill Clarke and the multi-tier educational program of which he is part. This program is designed to retrain adults in the area who have been left out of the work force (most residents of San Bernardino are on some form of public assistance), and to prepare younger ones to get and hold high-paying jobs.

Bill Clarke grew up in Boomer-era Southern California in a non-college family. “My dad told me that I had to get a degree, and that I should get a job I really loved,” Clarke told me last month. “I was fortunate enough to do both.” From the mid-1970s through the late 1980s he worked for General Dynamics in Pomona, as a manager and trainer in their advanced-automation divisions. In the late 1980s, while beginning work on a doctorate in educational management, he switched to the staff of the local community college, San Bernardino Valley College, where he headed their training departments for advanced manufacturing and welding. And through all those years, 1974 through 2008, he spent the mornings teaching at Fontana High School in their manufacturing-skills courses.

These were the years when, with some ups and downs, Southern California was still generally booming, and the skills Clarke taught prepared students for higher-wage factory and construction jobs. But also during those years, “vocational education” and trade schools were falling out of public fashion, because of the conceit that white collar positions automatically meant brighter prospects and better pay. (Why do I call it a “conceit”? The past decade has brought a reminder that skilled technical positions—in maintenance and repair of advanced machinery, in healthcare fields or other laboratory work, in agricultural or food technology, in logistics and construction—are the era’s fastest-growing “good” jobs.)

By 2010, San Bernardino Valley College had decided to phase out the machine shop Clarke and been running, and he was ready to retire from his teaching role there as he had earlier retired from the Fontana public schools. By that time he had become friends with Mike Gallo, the aerospace entrepreneur whose Kelly Space & Technology is the city’s leading tech firm. “Mike said, ‘Why don’t you bring your equipment over to my place and teach here?'” Clarke told me. “I said, I don’t want to teach any more. And then he said, ‘Well, what if we started your own school?'”

The result (skipping past some other details) is Technical Employment Training Inc. (TET), a non-profit, 501(c)(3) trade school for adults that now operates in a building at the former Norton Air Force Base, now San Bernardino International Airport. Gallo is its CEO; Clarke is its president; and its ambition is to train the city’s now-unemployed adults for middle-wage jobs available in the area’s hospitals, warehouses, factories, and construction sites.

• A “comprehensive, immersive training environment,” in which students work in a machine shop six hours a day, five days a week, for six months.

• Nationally recognized credentials and certificates at the end of the program, so that their training is officially recognized and is transportable.

• A realistic, on-the-job training environment, in which students produce real products on real machinery and thus can go to employers with real-world experience.

• Placement connections with local employers, of whom the region’s fastest-growing at the moment are in health-care and logistics. (San Bernardino, as I’ll explain in one more installment, figures that its main comparative advantage is as a warehouse site for the huge Southern California economy.)

I realize that most multi-point plans sound platitudinous. But TET’s approach resembles strategies we’ve seen work elsewhere: for instance, the one at East Mississippi Community College. Nearly 400 local people have completed the full program program at TET, Clarke said: “And we have put most of our graduates back to work in the high-tech manufacturing world. There are thousands of these high-tech jobs out there. We cannot train people fast enough for them.”

TET is designed for adults who have already run into problems in the modern working world. Meanwhile Gallo (as president of the school board), Clarke, and their allies are launching a parallel effort to prepare the city’s school children to be ahead of the game.

Bill Clarke took me to see what this meant, in practice, at two public schools that would normally be classified as “troubled” or “have-not” in political discussions. As we drove up to Captain Leland Norton Elementary School (“Home of the Aviators”), we passed three police cars on patrol. There and at nearby Indian Springs High School (“Home of the Coyotes,” where a large team of security officers was biking around the campus), virtually all students arrive with financial, educational, linguistic, and other family-background challenges.

But these are the places where the San Bernardino school system has made a commitment to training students for skilled-technical jobs. (For similar efforts we’ve seen elsewhere, check Deb Fallows’s story about the “Elementary School for Engineering” in South Carolina, John Tierney’s on the Maine Maritime Academy, and mine about the “Career Technical Academies” at Camden County High School in Georgia. Plus see this NYT article on a related effort in New York.)

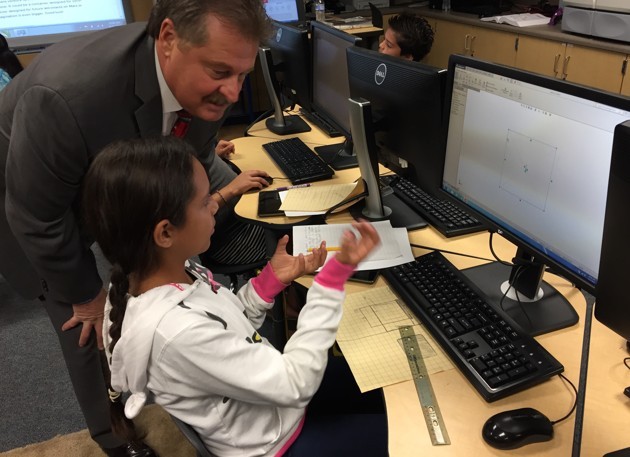

In elementary school, this means lots of training in digital tools. Mike Gallo sent me a picture of a Norton third-grader showing him the SolidWorks 3-D design program:

Gallo added in an email:

This is the EXACT same program my rocket scientists use to develop the latest rocket test systems for NASA’s space shuttle replacement vehicle.

This is the student engagement environment and culture of high expectations that our students are now able to experience. This will transform San Bernardino and provide them with the passport to prosperity!

At Norton I also saw a news broadcast entirely planned, reported, produced, and narrated by teacher Beverly Sayson’s grade-school students. Among other tools they used the green-screen in this studio:

Sayson also showed off some of the toys, precision parts, blocks, and so on that the students had made with the 3-D printers in their classroom.

Let me take a moment again to say that these are students from poor and poorly educated families, in a chronically low-ranked school system, where they are being engaged rather than warehoused or ignored.

At Indian Springs High School, Clarke showed me a fully outfitted machine-tool work shop, in which students are trained and then certified for highly-skilled trades. The photo at the top of this page was a recognition of one 14-year old for completing a high-level machine-tool course.

We’ve built our elementary school lab, and middle school, and high school, so that soon students here will have a genuine pathway,” Clarke told me. “By 2017, all 17,000 students in all San Bernardino schools will leave one of our nine high schools with real-world credential in a growth-demand sector.” These sectors, according to Clarke, include healthcare and medical technology (strong in the region), logistics and transportation (ditto), and manufacturing. This model—giving all students a “normal” education, but also equipping them with technical skills—is one we’ve seen in action elsewhere and have come to respect.

Can any of this happen? Are the odds too stiff? I don’t know. By itself will it solve San Bernardino’s problems? Certainly not.

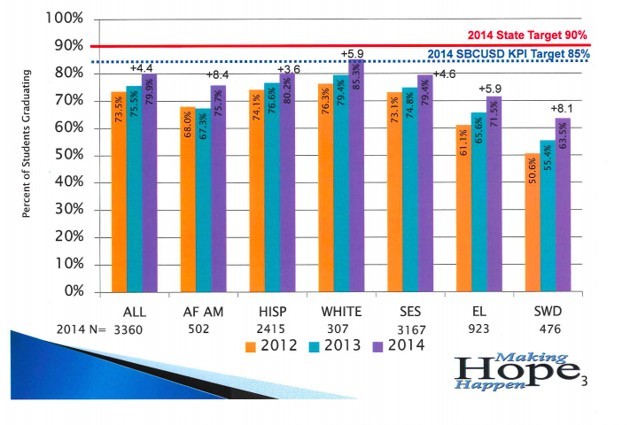

But after spending time with people like these and in their classrooms and with their students, I do know two things. One is that the school system is now moving forward rather than back, as suggested by the charts below. The other is that in a famously “failed city” with a long-struggling school system, people are working hard to give others a better chance.