Search for the town of Keene, New York on Google Maps, and you’ll see it appears small. Search “Keene, New York population” and you’ll find that only about a thousand people call the quiet Adirondack mountain village home.

Yet, Keene has attracted visitors in droves since the 1800s because of its picturesque landscape in the heart of the “High Peaks Region,” with Lake Placid to its west and Mount Marcy, New York’s highest mountain, to its south. Even America’s wealthiest families, like the Vanderbilts and the Rockefellers, built summer escapes there. Skiing, hiking, kayaking, rock-climbing – you name the outdoor activity, Keene has built a big reputation for it.

Like so many others, longtime visitor Jery Huntley fell in love with Keene’s natural beauty. But for Huntley, Keene’s charm was more than its soaring mountains and winding rivers. Keene’s history as a vacation destination since the Gilded Age gave way to a rich cultural heritage that fascinated her. When she eventually bought her own cabin there after 35 years of visiting, Huntley began to wonder how this history might be best captured. The local population is aging or moving away, and although the Adirondacks themselves weren’t in danger of being forgotten, the same couldn’t be said of the town’s history.

There are those who retire to actually slow down, and there are those, like Huntley, who might leave their day jobs but continue finding plenty of projects to fill their time.

Arriving to Keene newly retired, Huntley continued wrestling with her concern of how to preserve Keene’s history for generations to come. She saw the value in recording this history for its own sake, but her priority in capturing the town’s stories was for the community to hear and engage with them somehow.

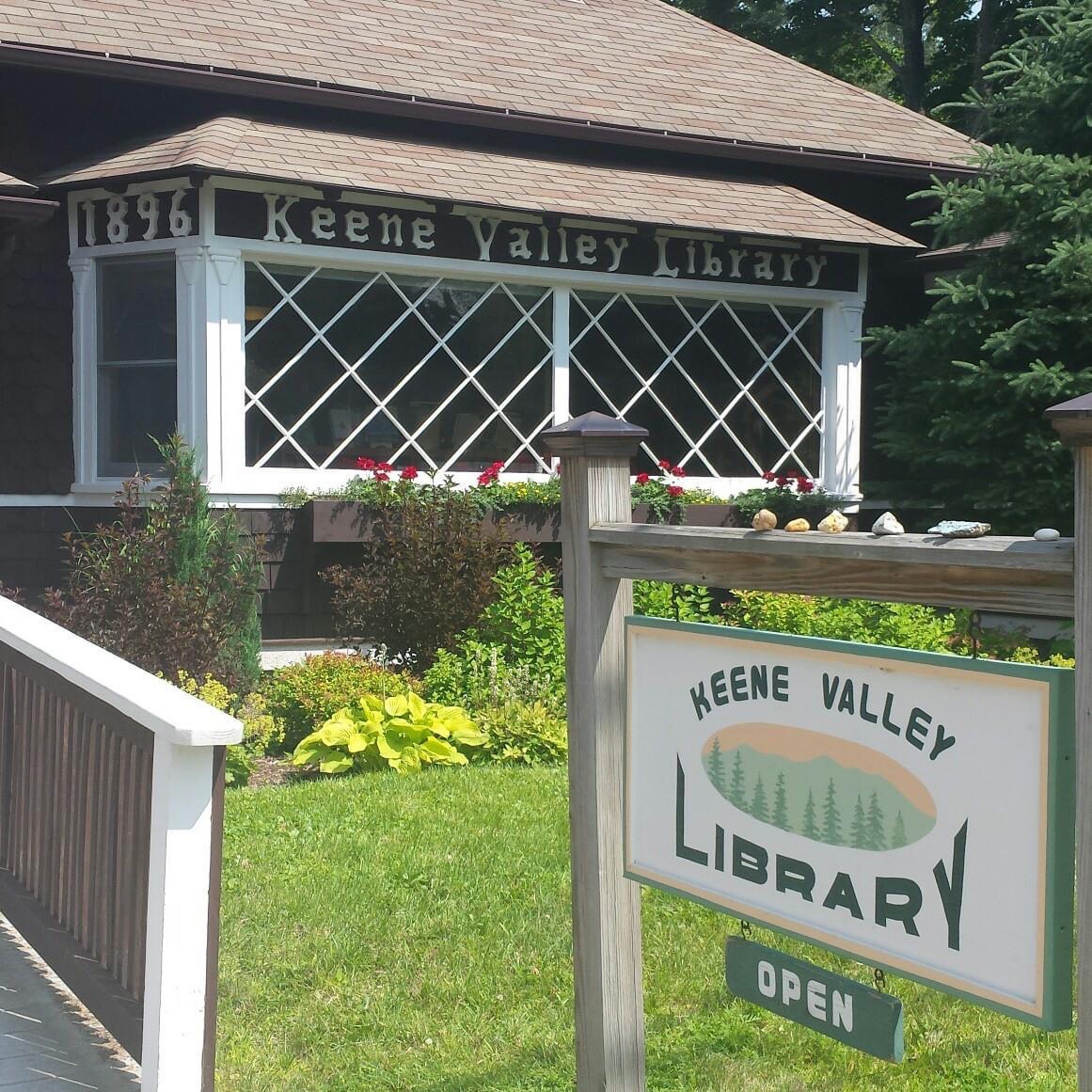

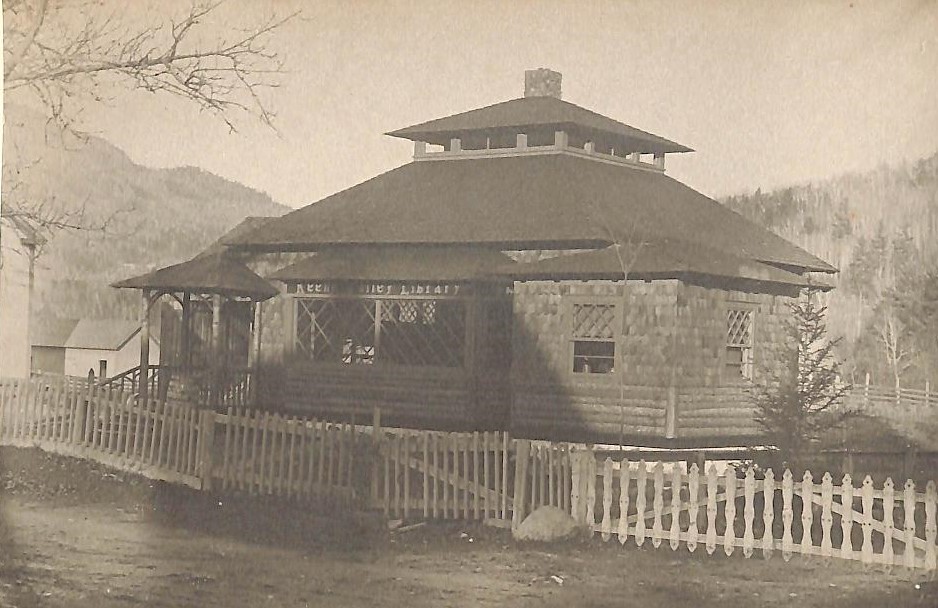

As a librarian and teacher early in her career, Huntley knew that libraries had long been in the business of maintaining town histories. So she teamed up with the Keene Valley Library in 2019 to dream up Adirondack Community Story Project, an online platform that houses 3-5-minute-long stories of Keene, told by Keene residents, for Keene.

Photo courtesy of the Keene Valley Library.

“The project was intended to meet the needs of the community, which were to record the stories of the past and present, because it has a unique cultural heritage, and bring them to the kids so they become active citizens in the community,” Huntley said.

Adirondack Community Story Project was successfully sharing Keene’s stories with the community before the days of COVID-19. But when social distancing measures and freezing mountain temperatures kept Keene residents indoors and separated from their neighbors, the stories began connecting residents in even more profound ways.

One resident described the impact of the stories to Huntley, telling her:

“On cold winter evenings in our harsh Adirondack climate, I often felt sad, so I’d listen to stories on the Adirondack Community website and hear about people in this community helping each other through multiple disasters and challenges. The stories warmed my heart and helped me get through two COVID winters.”

It didn’t take long for Huntley to realize that if the Adirondack Community Story Project could work in Keene, it could work elsewhere. She called on more than four decades of experience in the nation’s capital, where she learned to scale projects nationally, first as a legislative assistant to high-ranking politicians, and then as President and CEO of the Vinyl Siding Institute trade association.

“I saw the impact in the community and how much the people appreciated it. Then I got my Washington, D.C. frame of mind back and said, ‘we could do this all over the country.’”

Enter OurStoryBridge: a storytelling model, based on the Adirondack Community Story Project, which towns across America can use to capture and share the stories of their town. OurStoryBridge even makes it easy for towns to bring their stories to the youngest generation through the Teacher’s Guide, which organizes stories from across the country into categories based on subject. You can read more about all the resources available for towns wanting to run an OurStoryBridge process here.

When OurStoryBridge launched in September of 2020, over 400 people tuned in online to hear the announcement. Shortly after, three communities outside of Keene — Igiugig, Alaska; Tremonton, Utah; and Lake Placid, New York — began their own OurStoryBridge projects, which you can see on their project websites here, here, and here. Most recently, the Steger and South Chicago Heights community in Illinois has started its own project, which you can see here. Since launching, the OurStoryBridge model has yielded 300 stories in total.

Igiugig Village, in southwest Alaska, is in the early stages of its project. The 70 residents, called Igyararmiut (the people of Igiugig), are of Yup’ik, Aleut, and Athabascan heritage. They practice subsistence living through hunting, fishing, and gathering food. The tribal villagers named their OurStoryBridge Project “Niraqutaq Qallemcinek,” which means, “Bridge of Stories” in their Yup’ik language.

AJ Gooden was a librarian and schoolteacher in Igiugig when the community began its OurStoryBridge project. While not Yup’ik herself, Gooden says the community has welcomed her and that now Igiugig feels like home to her. She has since relocated to Kansas but continues to manage the Niraqutaq Qallemcinek from afar, with support from Igiugig’s governing Tribal Council. (OurStoryBridge projects require an organizational sponsor, which can be any organization from a library to historical society, from non-profit to for-profit)

“I knew OurStoryBridge was right up Igiugig’s alley because storytelling is culturally important,” Gooden said. “Traditionally, the people of Igiugig do a lot of singing and dancing to tell their stories to preserve knowledge from ancient people down to the present day. There has been a lot of disruption to that process over the past hundred years.”

Gooden is collaborating with local teachers to bring stories from the Niraqutaq Qallemcinek into Igiugig’s preschool, elementary, and high-school classrooms, which serve around 25 students. Those teachers are now helping to collect stories, and Gooden says she hopes to one day have all 70 Igyararmiut voices, including the children, represented in the Niraqutaq Qallemcinek.

Gooden also has plans to translate the stories, which were told in English, into Yup’ik, and the Igiugig Tribal Council has recently received federal funding to support this effort. Preserving oral histories in Yup’ik is a way to safeguard and teach the tribal language to future generations. According to Gooden, this is “all part of the Village’s mission to revive, preserve, and honor local knowledge.” In fact, Igiugig is one of many places where efforts are being made to prevent indigenous languages from becoming extinct.

The educational implications of OurStoryBridge projects go beyond Igiugig. In Keene Central School, social studies teacher Brad Hurlburt serves as the liaison for the Adirondack Community Story Project, and he uses the OurStoryBridge Teacher’s Guide to facilitate learning opportunities for the next generation.

“Assigning stories collected through OurStoryBridge is an interesting way to introduce topics in the classroom, whether it’s an economic recession, natural disaster, or war,” he said. “They are available as primary source documents for research and writing projects as well.”

What’s more, “the stories are inherently engaging. It’s tapping into one of the oldest forms of human communications in a format that’s very palatable,” Hurlburt said. “You don’t have to have a huge attention span. In a 3-to-5-minute setting, you get a really captivating perspective on topics that are real histories.”

He hopes that as stories are added to the OurStoryBridge canon, students from across the country can draw connections between what they learn in the classroom and what they experience outside it.

While she might be retired, Huntley is no closer to slowing down than when she first launched the Adirondack Community Story Project. She continues to volunteer her time to bring the OurStoryBridge model into more communities across the country.

“This is a community building exercise,” she said. “We are connected by our stories, and it’s important to share them, especially with our kids.”

From current residents to future generations, from Alaska to New York, Chicago to Utah, OurStoryBridge is helping towns uncover and share their rich cultural heritage, no matter how large or small they might appear on a map.

Residents interested in exploring how OurStoryBridge might help span their town’s past to its present to inform residents well into the future can learn more thanks to the free resources available here.