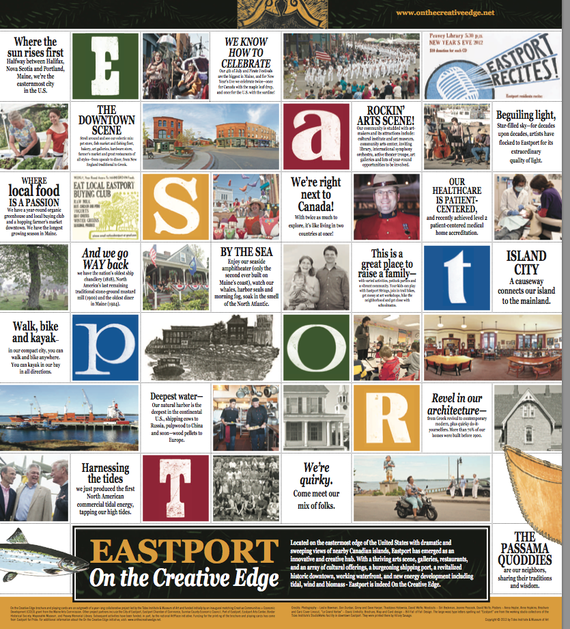

If you’ve been following the reports here by Deborah and Jim Fallows in their American Futures series, you know that the small city of Eastport, Maine, a town that has faced hard times in the past, is a place with lots of good things going on. Most recently, we’ve learned from Deb about the positive, “yes-we-can” attitude that has become widespread there, reaching into (and being reinforced by) the language people use. And from Jim, we’ve heard about efforts to build harbor traffic for the deep-water port there and an ambitious, large-scale project to harness the hydro-kinetic power of ocean tides and river currents.

Now let’s look in on another bold venture in Eastport, this one of much smaller scale and different orientation, but no less important in the way it’s helping to revitalize this coastal community. This is the story of how an art museum — The Tides Institute & Museum of Art — got started there in the past decade, and what it’s come to mean in the life of this small community of 1,300 people.

Hugh French, an Eastport native, and his wife, Kristin McKinlay, were living in Portland, Maine, in 2002 when they decided — in the great American spirit of mobility — to move. Where, they weren’t exactly sure.

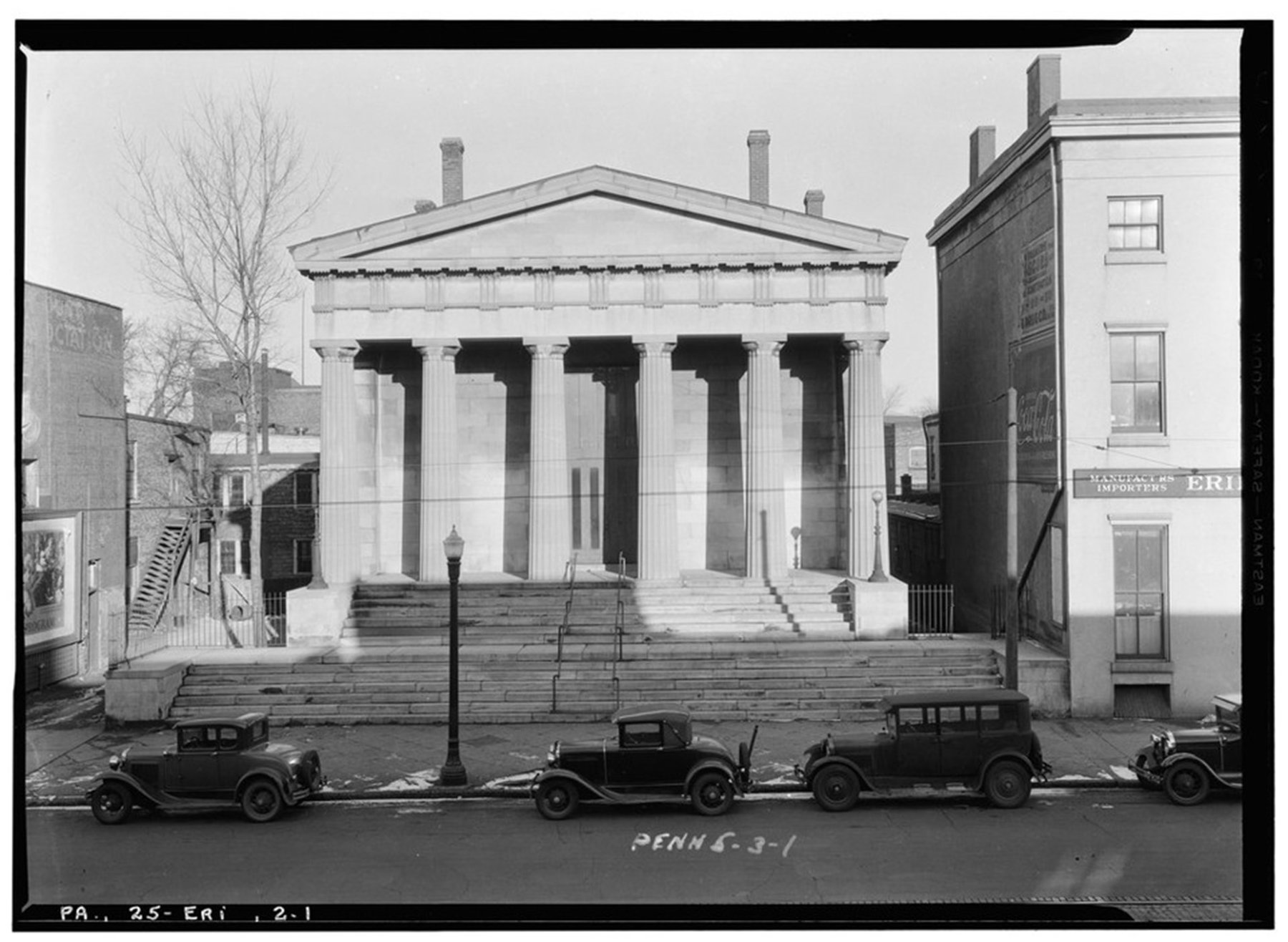

But on a visit back to Hugh’s hometown, they saw an old, dilapidated building for sale, the former home of the Eastport Savings Bank, and decided, virtually on the spot, to buy it and create an art museum there.

Laughing at the memory, McKinlay told me: “We went through the building. It was in dire shape, and yet we came out saying to each other, ‘We have to do this.'” Laughing harder, she said, “It was somewhat a matter of putting the cart before the horse.” What she meant was that they hadn’t previously made a conscious decision to move back to Eastport, much less looked for or purchased a home there, but they bought the building anyway, planning to create a museum. Their thinking, I realized as McKinlay explained to me the origin of the Tides Institute, was akin to Ray Kinsella’s inspiration in the 1989 film Field of Dreams: “If you build it, they will come.”

They saw something in that run-down building: hope — and a future. “We realized there was a need here for the kind of cultural institution that could help revitalize the town,” French said. “We knew that Eastport needed a cultural anchor; that was the genesis of the concept. Of course, we knew it would be hard: the town has a small population, there’s little money here, and there’s no big urban center nearby.” But they went ahead anyway, believing in the project — and in the town. “We wouldn’t have done it if we didn’t feel Eastport was already moving in a positive direction,” McKinlay said.

They started out, McKinlay told me, by “putting up a website first. We did that even before we moved from Portland to Eastport. We wanted to elicit responses from people up here about what was needed. So, having a website made it useful to gather ideas about collections, research resources, and so on. Also, potential funders were able to look at it.”

They chose the name with deliberation: rejecting Eastport or Passamaquoddy in favor of Tides, thinking it to be less limiting geographically, but still suggestive of the area and the community’s aspirations for connection to the world beyond. (“Tides connect everywhere,” French noted.) And they chose Institutebecause they felt it implied the kind of innovative institution they were hoping to create, with an educational mission and “an open-ended institutional capacity.” French explained, “We didn’t want to needlessly box ourselves in.”

Thanks to family heritage, French already had a collection of objects on which to build — paintings, historical photos, oral histories, and the like — much of this, cultural material about the sardine canneries that once dominated the economic life of Eastport. But they knew that building a museum meant they’d have to add substantially to their collection.

Helping to make that happen was the French family name, well known in town. McKinlay explained: “It’s been crucial to our success to have a known quantity in town doing this. Previously, there wasn’t an institution here that people knew and trusted, so people who had artwork, documents, or other valuable things to donate sent their items elsewhere – to other museums around the state or beyond, to the archives of their alma maters, etc. But because people knew Hugh, knew the Frenches, they were willing to give us their items of value. So, things started coming in.”

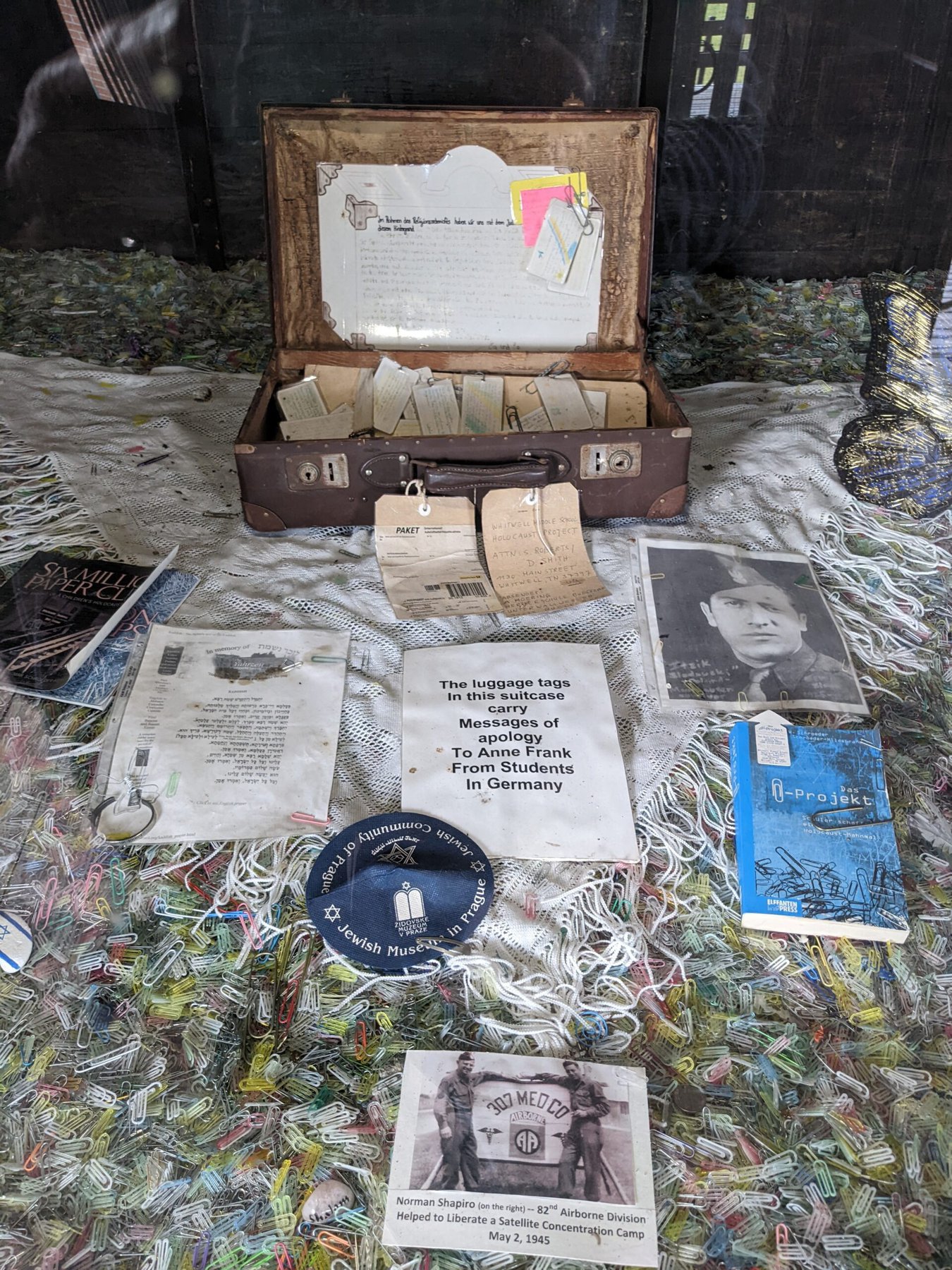

The museum’s collections cover different time periods and places, but are regional in many respects. Included among the kinds of items in the permanent collection are Native-American basketry, hand-painted ceramics, boat models, portraits of ships, and photographs from the sardine canneries. The total museum space is allocated roughly evenly between the permanent collection and special exhibits.

Once their extensive reconstruction of the building was completed, French and McKinlay started doing exhibits right away. That helped to build the collection, too. “People would come in to see exhibits and say ‘Oh, I have something you might want to add to your collection.'”

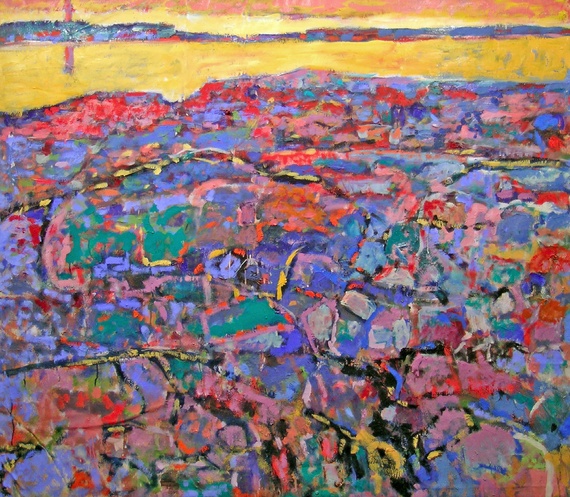

One of their recent exhibits showed the work of Andrea Dezso, a well-known artist who happened to come through Eastport, saw the museum, and approached French and McKinlay, saying, “I’d love to work with you.” So, she put together an exhibit based on her research on the area. Some of her work was her take on the imagination of a child working in the sardine canneries, one piece of which is shown below.

Another exhibit, this past summer, featured the installation of a separate structure on the plaza in front of the museum, containing a large camera obscura. McKinlay said that the exhibit, called Vorti-Scope, was “terrifically engaging to people of all ages.” (This video shows Vorti-Scope when it was installed in Fredericton, New Brunswick.)

When the Tides Institute first opened, it was one of the few places in Eastport open on Sundays. Sometimes the fledgling museum had only one or two people come in over the course of a Sunday – or nobody at all. Now, on Sundays in the summer, it’s not uncommon for as many as 150 people to come through.

Apart from building their collection and attracting an audience, another constant worry for French and McKinlay has been financing. But they’ve had some encouraging success on that score, too. For example, they applied for funding from ArtPlace, which is a collaboration of national foundations, banks, and the National Endowment for the Arts, aiming to promote public interest in the arts, encourage “creative place-making,” and support efforts to transform communities that are making strategic investments in the arts.

When French and McKinlay applied for an ArtPlace grant a couple years ago, theirs was one of approximately 2,200 initial applications, out of which 200 were invited to make final applications. Only 47 grants ultimately were awarded – one of those (for $250,000) to the Tides Institute. “We’re the only institution in Maine ever to get money from them,” French told me, attributing that success to the attractiveness of the idea behind one of the Tides Institute’s missions, “to build connectedness and engage people in the community, including across the border in Canada.”

The ArtPlace grant helped subsidize the restoration of another old (1887), rundown building nearby that French and McKinlay acquired. This second space, now renovated, houses their StudioWorks facility, providing studio space, with print-making equipment, a letterpress, and assorted digital resources. The building also serves as home to an artist-in-residence program that has grown rapidly in popularity, receiving 70 to 80 applications for the four sequential residencies available this past summer. The program is attracting the attention of artists, in part because it provides recipients with a stipend, along with free housing in an attractive space a block away.

The artist-in-residency program is dear to McKinlay and French because it helps meet their purpose of engaging the community. They want people to see artists at work in a studio, and they ask the artists to do work that people can participate in. Similarly, they run an educational program that, in addition to bringing school kids into the museum on field trips, also sends artists into the local schools to talk to kids about what artists do and to show some work. “We want kids to know that becoming an artist is one potential path ahead,” said McKinlay.

In the spirit of trying to strengthen the bonds of community, another important venture of the Tides Institute is its New Year’s Eve Celebration, which started about six years ago. French told me, “We commissioned an artist to create an 8-foot sardine that gets lowered from the roof of the museum at midnight, like the crystal ball at Times Square. It’s a very popular event. Hundreds of people come out for it.”

Looking back on what they’ve accomplished, French and McKinlay are proud of seeing their two buildings restored and happy to see how their efforts are contributing to the growing vitality of this small city. They’re gratified, too, French said, at how the Tides Institute & Art Museum has “encouraged cooperation and exchange among communities here on both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border.”

Not only would they do it all again, despite the formidable challenges they’ve faced, but they’d offer encouragement to others considering starting new ventures in the arts. As McKinlay put it. “I’d say to them, You can do it. You can be creative. You canbe innovative. Yes, it’s true: you have to be a little crazy. And you have to be willing to make some sacrifices and take some risks. But there’s a great opportunity to make a difference, especially in small towns.”

French and McKinlay are the first to say that they didn’t do all this on their own. “This is a tight community. People here work together,” McKinlay told me. “But I think it’s true everywhere that people will try to be helpful when they see something coming along that promises to be beneficial to the whole community. That’s certainly what we’ve found. So, my message to people would be: Take that gamble.”

[All photos provided by the Tides Institute and Museum of Art.]