What it takes to motivate a community, and have people from different backgrounds and with different interests decide to work on a shared problem, is hard to know in advance.

In some places, it’s a response to a crisis or emergency. In others, it’s the effect of an individual or group with appealing or appealing ideas. In others, it’s the result of a deliberate process of community self-examination and planning. In still others it could be a combination of all these forces and more.

Here is an example from Washington, D.C. — a place that is usually in the news as the setting for national politics and government, but which is also a community where nearly 700,000 people live. In an article for The Atlantic three years ago, I laid out the connection between local politics in Washington, and what Deb Fallows and I had been learning about in other parts of the country:

Starting in 2013, my wife, Deb, and I traveled around the country to report on local-improvement narratives, which always seemed to begin with “I wondered why my town didn’t do _______, so I decided to get involved.” We’d long been active at our kids’ schools and with their sports teams. But we wondered why our town—Washington, D.C.—wasn’t doing something about the leaf-blower menace, given that an obvious solution was at hand. We joined a small neighborhood group—barely 10 people at its peak—to try to get a regulatory or legislative change, using noise, not pollution, as the rationale.

Yes, the object of that local effort was the use of gas-powered leaf blowers within the nation’s capital. As the first piece explained, what might seem like a fringe issue had in fact become a serious environmental and public-health concern. The primitive gas-powered “two-stroke” engines that powered these devices were so much dirtier than modern car or truck engines that authorities in California warned that their smog-producing emissions were becoming greater than the tens of millions of cars in the state, combined. Their carcinogenic fumes and damaging noise were harmful most of all to the work crews who stood in their immediate wake for hours per day.

That Atlantic story three years ago explained the civic-engagement saga that led to unanimous passage by the D.C. City Council of a phase-out of gas blowers, and a shift to battery-powered equipment, in the summer of 2018. A followup post last fall explained how the issue had changed from “fringe” concern to the forefront of local environmental efforts in a growing number of communities.

Now it is 2022, and the law has gone into effect. In a new post, first published on Substack but adapted because of its relevance here, I tried to draw some of the lessons of the local D.C. experience for other communities.

Here is an adapated version of that post:

Working Together, in Washington DC.

Daily news tells us about how law-making gets done, or doesn’t, in the divided terrain of Washington, D.C.

This is the story of how citizens worked together toward a common goal in Washington. The setting is not the District as a seat of national government but rather as the place where some 700,000 people actually live, pay taxes, and vote. The story involves a change on the local level with significant, positive implications for other parts of the country and beyond.

This change is the District’s ban, many years in the making and effective this past January 1, on the sale or use of gas-powered leaf blowers. These devices are the most polluting form of machinery still in legal use. But as of this month, their sale or use is no longer legal within the District’s 68 square miles.

I believe that ten years from now, the same will be true of most cities across the United States. The change will be gradual, then sudden—like the use of seatbelts in cars, or restrictions on second-hand smoke and then smoking itself. The change will be inevitable because:

- The pollution and public-health damage done by this machinery is so extreme;

- The less-damaging alternatives are appearing so fast; and

- The environmental-justice issues are so stark.

I’ll say a word more about each of these, which were also laid out in detail in this previous post. But I want to get to the lessons of what the District has done, and how people here have done it.

Why D.C. Acted—a Summary

You can find the detailed rationale for the District’s policy in this previous post and in the many references below, including the testimony the Council considered. [Here are more references: this 2019 article by me in The Atlantic; this explanatory post from our community website, Quiet Clean DC; this testimony to the D.C. City Council, before their unanimous vote in favor of the ban; and this statement on why the greatest damage from this machinery is inflicted on the crews who operate them, many of whom are low-wage, in many cases immigrants, and generally not covered by generous health-insurance plans.]

The arguments boiled down to:

- Extreme emissions. Gas-powered two-stroke engines inefficiently burn a slurry of gas and oil, and send out of much of the byproduct as toxic fumes. They are vastly more polluting than cars, trucks, or practically anything else. Using them is like heating your house with a bonfire in the living room. They also do great collateral damage to topsoil and wildlife habitat, including the eggs and cocoons of butterflies and fireflies.

- Noise damage to the users, and noise nuisance to the neighborhood. As explained here, the distinct low-frequency sound-profile of gas-powered blowers can lastingly harm the hearing of the work crews, and penetrates walls and windows in surrounding structures.

- Technological obsolescence. Two-stroke engines are the technology not just of yesterday but of a century-plus ago, and are so dirty they’re being phased out around the world. Batteries are the technology of today, tomorrow, and thereafter.

- Rapidly appearing alternatives. If Ford and GM can offer multi-ton pickup trucks that run on battery power, then blower-makers can do the same with ten-pound devices.

How D.C. Acted—the Ingredients

This has been a very long process. As explained in my Atlantic article, we started holding neighborhood meetings on this topic more than eight years ago. Over the next few years, our colleagues made presentations and held discussions in every part of the (highly diverse) District. We met City Council members and their staffers. We went to neighborhood meetings and spoke at hearings.

Finally in 2018, the City Council unanimously passed the phase-out mandate. It allowed a three-and-half year transition period, which took us until January 1 of this year.

The Atlantic piece I wrote nearly three years ago was after the Council’s action but obviously before this year’s enactment. In the piece I said that the lessons were the ones I’ve quoted below. I think they still apply to civic efforts elsewhere, with a few updates [noted in brackets]. The article said:

—Showing up matters. Our group met in person every two or three weeks over more than three and a half years. Perhaps our most indefatigable member, a lawyer, made presentations at dozens of ANC [Advisory Neighborhood Commission] meetings. [These were in every part of the District, which made a difference.]

—Having facts also matters—yes, even in today’s America. At the beginning of the process, it felt as if 99 percent of the press coverage and online commentary was in the sneering “First World problem!” vein. That has changed…. Reflexive sneering is down to about 5 percent among people who have made time to hear the facts. Noise, they have come to understand, is the secondhand smoke of this era. [And, as shown here, the tone of the press has dramatically changed. Last fall the New York Times gave most of its editorial page to an item titled “Let’s Kill All the Leaf Blowers.” You can see many other examples here.]

—Technological momentum and timing matter…Nearly everyone in the industry knows that 10 years from now, practically all leaf blowers will be battery-powered. One of our arguments was that we were simply accelerating the inevitable. [And in the three years since I wrote this article, the performance/price ratio of batteries has rapidly improved.]—Having a champion matters. At a “meet the council member” session on a rainy Saturday morning in the fall of 2015, [our DC Council member] Mary Cheh said she’d stay with the bill—if she could rely on us to keep showing up. We did our part, and she did hers—she stayed with it to the end…

The final lesson is: Don’t get hung up on the conventional wisdom—it’s only wise until it isn’t. Everyone says nothing gets done in Washington. This one time, everyone was wrong.

What D.C. Did Since Then—Implementation

Getting the D.C. law passed, unanimously, was a success of legislation. But all of us realized that it was at least as important to have the law be a success in implementation, and execution.

The classic cautionary example was that of Los Angeles. It passed a ban on gas-powered blowers back in the 1990s. But because battery alternatives weren’t really practical then, the ban might as well not exist. It would have been like an electric-car mandate, a generation before any such cars were on the road. (The whole state of California recently passed a ban on the sale—but not use—of gas-powered blowers, effective in 2024.)

The implementation process in D.C. is just beginning. But we understood that there were three main keys to putting the new policy into effect:

- Getting the word out, so it didn’t come as a total surprise;

- Easing the financial burden of transition, especially for small operators;

- Having a reasonable enforcement system.

We’re less than three weeks into this process. But so far, I will say that D.C. and its city government, often a convenient butt-of-jokes for politicians from the rest of the country, have set an impressive example of how to meet these targets. Other communities could learn from it.

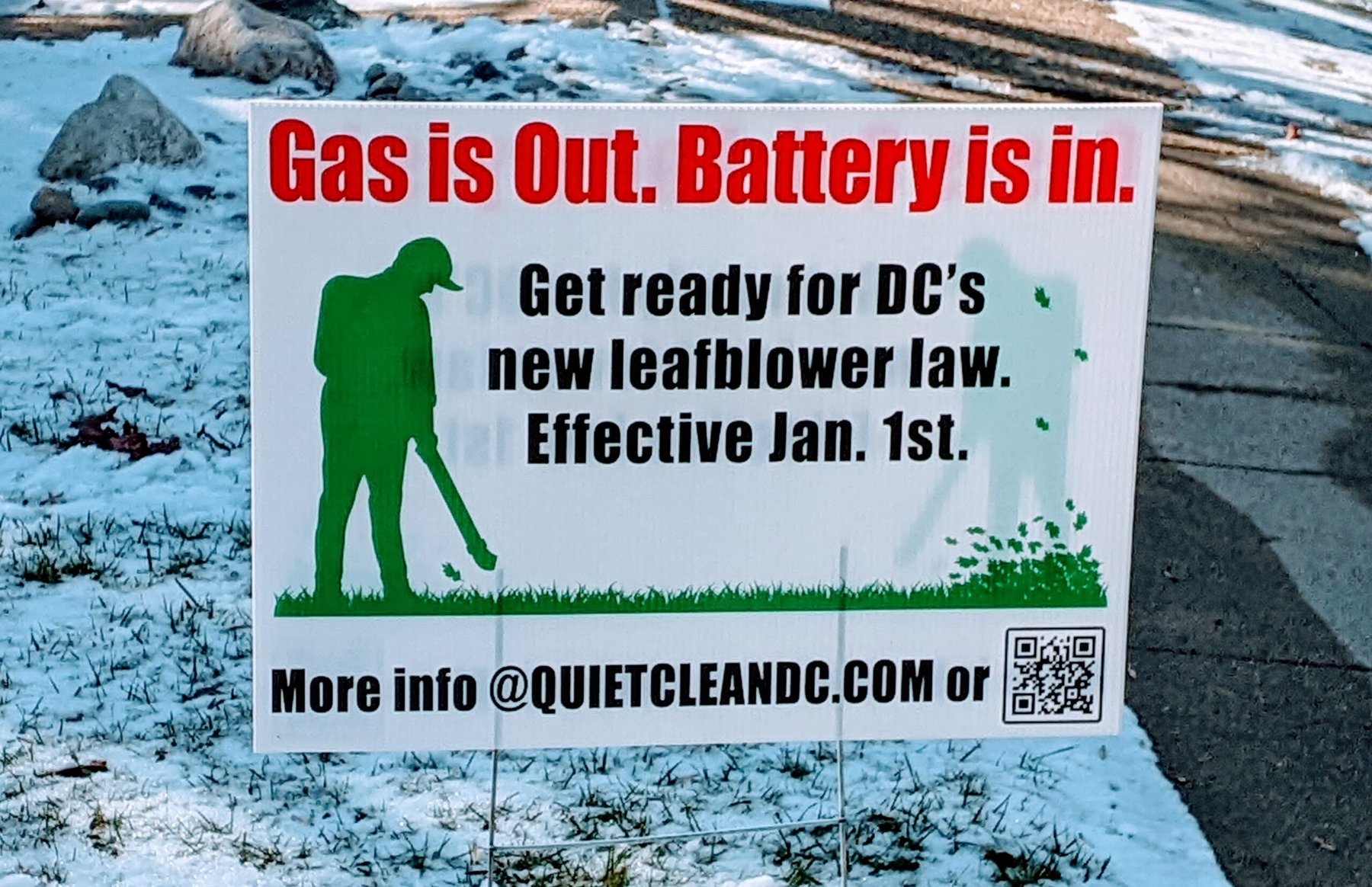

- On getting the word out, over the past six months, most members of the City Council have included reminders of the upcoming law in their newsletters and public statements. The District’s Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs (DCRA), which will oversee the law, has sent out repeated reminders to landscaping companies. You can see the announcement on the DCRA site here. And a sample message if you scroll down here. Members of our volunteer group printed up and distributed yard signs like the one you see above.

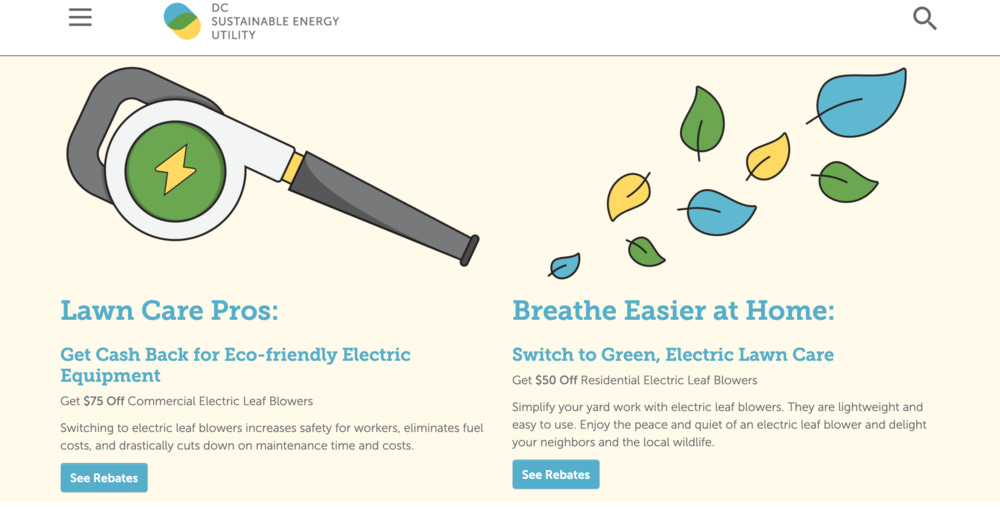

- On providing financial help, the District’s innovative Sustainable Energy Utility (DCSEU) created a rebate-and-subsidy program, to help speed the shift to battery-powered equipment. A local bank also announced a zero-percent financing program for small and startup businesses making the change.

- On enforcement, the DCRA wisely avoided the impractical whack-a-mole of imagining that inspectors would prowl neighborhoods in search of illegal blowers. Instead it has provided an online citizen-complaint form, similar to those it had previously established for violations of other noise and nuisance regulations. According to the new law, any use of a gas-powered blower is now illegal in the District. So a photo or recording of one in use is prima-facie evidence of violating the law.

When spring comes ….

Will implementation be smooth and friction-free? Of course not. Some people won’t know about the law. Others will ignore it. Some will think it’s a terrible idea. The next big reality test will be this spring.

But I will say that so far this year, I have heard exactly one blower operating, for about ten minutes total. It’s the dead of winter, but that’s far different from previous levels, which were hours per day at all times of year. The big companies, which are still operating during the winter, know that the rules have changed. We’ve seen some with battery equipment on their trucks.

And I will take any bet that ten years from now, this will be the standard practice in most American cities. The battery alternatives are just too attractive; the needless damage and nuisance are just too great. And between then and now, I think the often-maligned civic structure of the District of Columbia can be studied for the way it engineered this change.