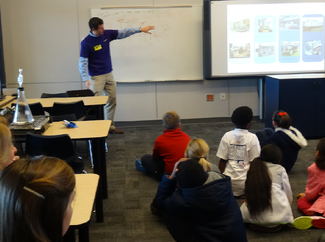

It was the monthly “engineering week” when I visited the A.J. Whittenberg Elementary School of Engineering in Greenville, South Carolina, in January. Volunteers from one of the several local big-name companies in town were teaching special lessons. This week, employees from General Electric, some in purple t-shirts, were teaching about hydro, wind, and solar power sources.

One volunteer was boiling water in a glass beaker, which produced steam, which drove a pinwheel to spin. Another was demonstrating the evolution of light bulbs, measuring the amount of heat the bulbs produced, and engaging fourth graders in a discussion of what it meant to a bulb that much of its energy was spent on producing heat instead of light.

Whittenberg is a public school that sits smack in the middle of an area that Lynn Mann, the school’s director of programs, described to me as a highly distressed area of Greenville, with high poverty, unemployment, crime, and single parent households.

The school also sits smack in the middle of the engineering mecca that Greenville has become. GE, Michelin, and BMW, which have strong manufacturing and research presence in the area, engage in so many ways with the town, including this elementary school. In fact the list of partners for the school numbers more than 2 dozen, including Fluor, Hubbell Lighting, Duke Energy, Furman and Clemson, among others, making it a classic example of the public-private ventures we saw throughout Greenville.

After a 40-year hiatus when not a single new public school was built in Greenville, it didn’t take long for Whittenberg to take off.* Ms. Mann told me that in first year, few people had gotten wind of the school, and they had to hire high school kids to canvass the neighborhood, introducing the school to parents and encouraging them to enroll their youngsters. (Families who live within a 1.5 mile radius of the school can enroll as its neighborhood school; others must apply. Today, about 1/3 of the 400+ students are from the neighborhood; 2/3 are from other parts of Greenville.)

By the second year, word was out, and parents camped out in front of the school for a week before registration for the first-come-first-served spots. It was so popular that the local Lowe’s home store offered discounts to parents for their camping supplies. Then it spun so out of control that the school switched to a lottery system for the out-of-neighborhood spots. Now, Ms. Mann told me, Greenville realtors advertise the in-town location as an advantage when listing houses in the Whittenberg district.

Here are some of the sights and insights from my morning at the school:

Unexpected sights: The walls of the fourth and fifth grade corridor are bare, except for digital screens. In fact, almost everything in the fourth and fifth grade is digital. It makes for a paperless environment, where all the schoolwork is done on tablets, students enter their work into folders, teachers use a stylus to comment on work, and parents are encouraged to open the folders and monitor the entirety of their children’s work.

How do the students handle this system? They are masters. They start keyboarding in kindergarten, with unplugged keyboards. By second grade they have each been issued an iPad. And they learn Power Point, not my favorite application but one certainly encouraged by the engineering community. The school does teach to print out block letters, and the students are graded on penmanship throughout their years. However – and this news comes as a Praise-the-Lord moment for me, a mother of boys – cursive writing is not taught! How much struggle, I reflected, our boys could have avoided without the hours they spent on cursive in elementary school.

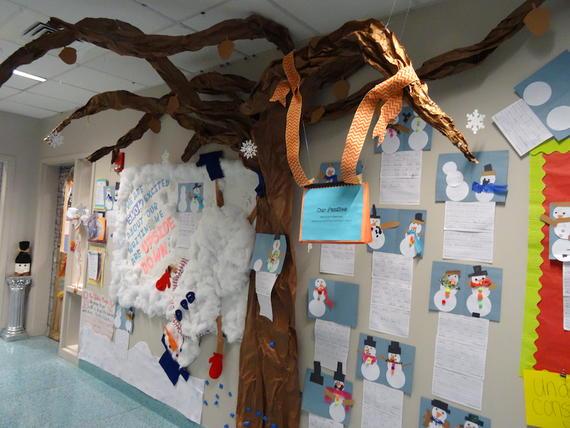

On the other hand, there is no shortage of art in the rest of the school. Corridor walls are bursting with 3-D extravaganzas. Children have created all manner of décor. There are paper trees growing out of walls, fluffy snowmen popping out, suspended robots and all manner of things that protrude and hang and dangle.

In the main hall, there is a column of pop-out paper cutting, in honor of a visit to Greenville by pop-up children’s book writer and illustrator Matthew Reinhart. Each classroom I entered was a creative heaven— sculptures hanging from ceilings, bursts of color everywhere, busy work stations, clusters of buzzing activity, books, furniture, photos, and one empty “thinking chair.”

This year, one production is the Wizard of Oz. First graders at Whittenberg study the production in every aspect. Lucky for the school, the productions for the last several years have included a “flying element”, which fits nicely into engineering lessons. This year, the first graders learned about what it takes to get the wicked witch up in the air. They broke into teams to design their own rope and pulley system to get a witch to fly. They walked the Swamp Rabbit Trail to the Center to learn about how the lighting works, how the orchestra pit operates, how the stages and scenery are set up. The winning design team got to attend a performance at the theater. They all learned the songs in the musical; they read the book; they made their own pop-up books of the story.

Extracurriculur manna from heaven. There is so much here that it left me breathless: The kids go to the Kroc Center for sports and after school programs of all sorts. They built an organic garden out behind the school, including a greenhouse constructed of recycled plastic bottles. This year, they’ll launch a cotton project, to grow and harvest cotton, tying that into the history of textile mills here in The Upstate of South Carolina. The school is part of a Culinary Creations program. I was delighted to learn that they have done away with teaching nutrition via the tedious food pyramid; here, the kids learn to identify green, yellow, and red foods – Go, Slow, and Whoa – to help them learn about proteins, veggie, low sugar fruit; carbs, high sugar fruit; cookies and cakes. They bake their own bread and make their own homemade soup on site. Some 57% of students are on free or reduced-price lunch.

Environmental service is a schoolwide effort. First graders compost. Second graders collect recycling waste from rooms every Thursday, sort and count it and rate the owners of the recycling bins. You get plusses for volume of recycled material and demerits for – heaven forbid – candy wrappers. Third graders measure air quality and post signs outside promoting a no-idling campaign for cars. Fourth graders study water quality and present power points (!) about it to the other classes. (A curious aside: at least 4 people in Greenville told me the city boasts the “Best tasting water in North America.” I’m not sure where this comes from. But the water was good enough to take away the stigma of choosing tap water over bottled water at high-end restaurants.) Fifth graders learn how to do home energy audits.

I asked about foreign language teaching and was expecting to hear about some fancy new program for Chinese or an activity-rich effort for Latin. But no. When the school consulted the engineering gurus about foreign language, they responded that the world’s engineers all spoke English and recommended instead that the school teach English as well as they possibly could. This, and the goal to master Power Point by second grade, may be the only two issues where I would part ways with A.J. Whittenberg Elementary School of Engineering.

The future? A new public middle school for engineering is opening next to the CU-ICAR (Clemson University International Center for Automotive Research) campus in Greenville next year. A public high school for engineering is in the planning stage.

If you’d like to see the spirt of the place, please, take a look at this video.

Photos by Deborah Fallows.

* correction: In fact other schools had been built in Greenville during the past 40 years. But a school had been promised to this inner city community for 40 years. See here.