Several times this year, I have made cryptic mention of a new reporting project I was excited to undertake.

It’s called “American Futures,” we’re unveiling it today, and over the next few days I will be doing a series of posts to lay out the rationale, the ambitions, the practicalities, and the challenges. Then, early next week, my wife and I will head off for the next stages of reporting.

The short way of describing this project is to say that it’s a version of the classic American road trip, conducted by air. The longer version involves this background:

- As a boy, like many American children, I loved and learned from road trips, and never tired of them. From as early as I can remember, I’ve been excited by the adventure of seeing what was around the next corner — and how the the place we were headed was different

- from the place we had left, and how the people and landscape changed in between. My parents must have gone crazy, driving three children below age 5 coast-to-coast in a station wagon, and then back the other way in a passenger train. We were engrossed. With my high school friend Greg, I spent a long time on a Pacific Coast road trip. With my brother Tom, a journey through the 1960s-era American south.

- Through our married life, my wife and I have also stayed on the road — in Africa, in Texas and the Pacific Northwest, through Southeast Asia and Japan, recently in China.

- In my reporting life, I’ve gotten most enjoyment and education from climbing on a bus, a train, a boat, a plane, and being surprised by what I found when I got off. When I worked for Texas Monthly in the 1970s, I kept a highway map of Texas on the office wall and saw how much of the state’s roadways I could cover. Alpine, Van Horn, Eagle Pass, Alvin, West, Marfa, Gonzales — there were surprises in each place.

- Wherever we’ve lived, I’ve been aware of the big-city-centrism of the news, and how many things you didn’t know enough even to wonder about until you’d left the capital. In China this is how we got to Changsha, Zhuhai, Xizhou, Yinchuan, Yellow Sheep River, rural Gansu and Sichuan, and other places we found deeply rewarding. I’ve missed doing enough of the same thing at home.

- As a reader, I think I’ve memorized the chronicles of discovering America by traversing its territory. Travels With Charley when I was a kid, then the Dickens / Parkman classics in college, through Blue Highways and Flight of Passage. And just this week, Democracy in America in toto. (Whew!)

Some 13 years ago, my wife and I bought a small propeller plane. Since then we have traveled across the country many times — east to west, north to south. So far we’ve landed in 47 of the Lower 48 states. Mississippi, your time will come. Youlearn odd things through this kind of travel. For instance, America-by-air, from a low enough altitude to notice the details, abounds in three things you’re not as conscious of from the ground: windmills, quarries, and prisons. (It’s easy to spot prisons from the air. And every visitor to America, from at least Dickens onward, has remarked on their abundance.) And on each trip, we’ve spent time in places we would never otherwise have visited and perhaps not known about — Red Oak, Iowa; Scottsbluff, Nebraska; Twin Falls, Idaho. Each time we have felt as if we had learned things about the realities, good and bad, of American life, that we wouldn’t have known without traveling.

That’s the preface to, and premise for, this project. It is an attempt to tell parts of America’s story that are underrepresented in most news accounts, and where — in our experience — much of the adaptation to America’s next stage of economic, demographic, and social history is taking place. My wife and I have come back from every one of these cross-the-country trips wanting to tell our friends, You won’t believe what we just saw! It was so interesting…. And usually, so encouraging. We want to learn about, and tell, similar stories in a more systematic way.

Three organizations are closely involved as partners in this project. One, of course, is The Atlantic, where I have worked for most of my career and where both print and online reports of our travel will appear. Another is Marketplace from American Public Media, hosted by Kai Ryssdal (also a pilot), which specializes in exploring America’s changing economic realities. And the third is the technology company Esri — less well-known by the general public than the first two, but if anything more dominant and influential in its own realm — which is a pioneer and worldwide leader in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software. For this project we’re using it both to identify and assess types of cities to visit, and to display theresults through Esri’s brand-new “geo-blogging” software.

The most crucial partnership, of course, is between me and my wife Deborah Fallows. She is known to the world as a linguist and author of, most recently, Dreaming in Chinese and this popular Atlantic article. She’ll be known through this project for her reports on the practicalities of travel, language-and-life variations across the country, and other themes.

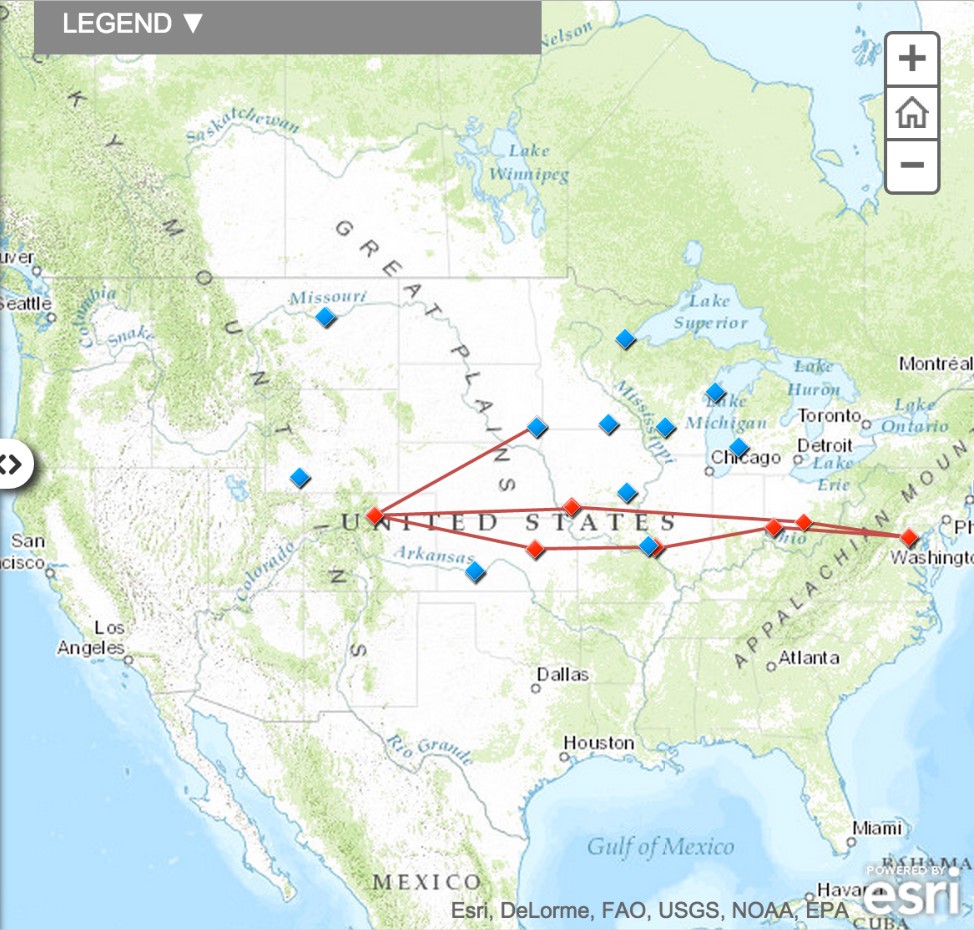

That’s enough for right now. In the next installment, I’ll say more about the kinds of cities we are planning to visit, and how we’ve chosen them; what’s novel and revelatory about Esri’s technology; how we’ll be working with Marketplace; and, yes, how we think about safety in small airplanes. For the moment, I leave you with one straightforward map, and one video.

The map above shows the work we’ve done so far. The red indicates the path of a “proof of concept” trip we made in our plane last month to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, a city about which you will be hearing a lot more. The blue diamonds mark the cities and small towns that we are lining up for the first “American Futures” swing, through August and early September, starting in a few days. More about them in the next few installments. We’ll be doing this region by region, and initially we are heavy on the upper Midwest and northern Plains areas, because of so many interesting and under-reported developments there. We have another 70 or 80 cities sized up, and I’ll discuss the criteria we have in mind.

This video was from the mammoth Esri User Conference earlier this month in San Diego, in which I presented to the map-conscious attendees an argument of how we would put geography to work in this effort. It’s introduced by Jack Dangermond, the founder and CEO of Esri — and, by good fortune (as you’ll see in the first half-minute of the clip — at first it will seem that I’m introducing this in humblebrag mode, but keep watching), someone with whom I grew up in Redlands, California, where his company is now based.

Thanks for reading and listening; we hope you find this as interesting as we expect it to be; and if you’re a small-town person, we hope to see you and hear your stories sometime soon.