Brownsville is the southernmost U.S. border town with Mexico, down at the very tip of the map of Texas. Across the Rio Grande is Matamoros. Some 20 miles to the east is the Gulf of Mexico. If you drive 60 miles to the north and west along the Old Military Highway to McAllen, you’ll see stretches of border wall, irregular in their size and design. It was very hot when we were in Brownsville last month. It reminded me of Nanjing, one of the so-called furnaces of China, where the soles of your sneakers sink into soft tarmac of the roads.

Elon Musk has built his SpaceX site on the road from Brownsville to the coast. It is an assembly site for now, in a clearing that looks like half moonscape, half desert, with giant, surreal, bright, silvery sections of rocket being welded together. The plan is for rockets to launch from here one day. Just beyond SpaceX, the Boca Chica road fades to sandy coastal beach. It feels like the edge of the Earth.

Border patrol agents cruise the highways and roads around Brownsville. One afternoon, as I was driving the highway north from downtown, a silent ambulance cruised by, with a border patrol SUV, caked with dust and dried mud, right on its tail. I realized that I didn’t have a clue of all that was really going on in Brownsville.

Some things about Brownsville are easy to see. The buildings of the downtown—many tattered now, featuring discount goods for the cross-border shopping market from Matamoros—still have great bones, as the architects say, and are waiting for their second chance. Brownsville was too poor to raze those buildings when businesses went dark, an obvious advantage now. (As we have seen elsewhere.)

A hip pizza and wine bar called Dodici opened recently in the old Fernandez building downtown. One of the owners is Trey Mendez, a lawyer who was just elected mayor in a run-off contest while we were visiting. The Market Square area is newly renovated, as part of a downtown-revival program under the mayor for the previous eight years, Tony Martinez. Brownsville has an outsize number of museums, including the Brownsville Museum, which is a real gem. The Mitte Cultural District boasts “something for everyone” with its zoo, pool, pavilions, playhouse, and much more. RJ Mitte (who played Walter White’s son in Breaking Bad) is of that Mitte family and is carrying on the family philanthropic efforts of his grandfather. Other buildings are works in progress. More are still pipe dreams.

Of course, you cannot miss the border wall. The wall near downtown‘s Gateway International Bridge has been there for about 10 years, long enough that the landscaping and vegetation along its river pathway and Alice Wilson Hope Park on the U.S. side have grown in to looking normal.

On our first evening in Brownsville, when the heat of the day had subsided a little, Jim and I decided to walk across the International Bridge into Matamoros. How could we not? We had no chance of entering the detention centers that have become so notorious in Rio Grande Valley and elsewhere along the border. We wanted to have at least a look at the routine daily flow north and south.

Our crossing was entirely simple and uneventful, of course, just like it is for residents of both Brownsville and Matamoros who cross the bridge daily for school, jobs, shopping, dinners out, or visiting friends and family. (Brownsville’s population is roughly 95% Hispanic, and many people have longstanding ties across the border. The inter-connectedness of the two cities’ lives is the central theme of an acclaimed recent novel set in Brownsville: Where We Come From, by Oscar Cásares. When we were in town, then-Mayor Tony Martinez gave us a copy of the book.) Along with a small handful of people also making the trip on foot, we deposited four quarters in the turnstile and pushed our way through to Mexico.

I looked up and down the river, assessing it with my swimmer’s eye, thinking how surprisingly narrow and benign it seemed, maybe 50 yards wide. The river was dark and muddy, not in the least inviting, even in the heat. The Rio Grande appeared to have no current. But of course we all know that surface appearances can deceive, as they most certainly did in the horrific episode when Oscar Alberto Martinez Ramirez, of El Salvador, and his two-year-old daughter, Valeria, drowned trying to cross it not far from this spot, a few days after we were there.

Brownsville residents, who have lived all their lives as part of a binational community extended on both sides of the river, have a different sense of the border from those for whom it’s an abstraction. “We don’t think of it as a border,” we heard from so many people that we stopped counting. “We think of it as a river.” I realized that it was just the way those of us who live on the border between Washington D.C. and Virginia think of the Potomac.

Beyond these impressions of Brownsville, there are data points that are more quantifiable. This is where the public health issues come to the forefront, and they are stark. (My thanks to The Atlantic’s Faith Hill for help collecting this data.)

Some 51 percent of the adult population in the area are obese; an additional 34 percent of are overweight.

Of children 8—17 years, 54 percent are obese, compared with about 33 percent nationally. Joseph McCormick, until just recently the dean of the Brownsville campus of UTHealth School of Public Health wrote in an email: “These children have higher BMI, higher waist to hip ratios, higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures, higher triglycerides and LDL (bad cholesterol) lower HDL (good cholesterol); They had higher insulin resistance (a precursor to diabetes, and elevated liver enzymes suggestive of fatty liver disease, a very common problem in our population in adults.”

Some 27 percent of adults have diabetes, about three times the national level. About one third of those with diabetes didn’t know they had it before being tested.

Only 42 percent of Brownsville’s population have some kind of health care insurance.

For more positive comparative news, life expectancy in Cameron County, which includes Brownsville, is about 80 years, four years longer than the national average.

And Texas has one of the country’s lowest rates of deaths from opioid-involved drug overdose, 5.1 for every 100,000 people, compared with the national average of 14.6.

Brownsville is a poor town; nearly 31 percent of the residents live in poverty; 38 percent of children. The median income is $35,000. Some 87 percent of school children in Cameron County qualify for free and reduced lunch.

* * *

I had lunch one day to talk about these statistics with Rose Zavaletta Gowen, a medical doctor who grew up in Brownsville, trained in Dallas, and returned to practice medicine. She soon turned to public health advocacy and added a new role as an elected city commissioner. Gowen frames her thinking, advocacy, passion, and action plans for her hometown this way: “We traditionally think we need economic development and education, and we’ll get to health later or afterwards.” She adds, “but later may be too late and putting it off hinders progress in economic development and education as well.”

Rose Gowen is part of Brownsville’s Community Advisory Board (CAB) , a network of more than 200 Brownsville residents and individuals from health care, education, business and community groups, and the UTHealth campus, which, with its newly-appointed dean of the campus, Belinda Reininger, has been key in founding and support of the CAB. All together they are pushing toward building a healthier population and lifestyle, in a very Brownsville-specific way.

Every community we have visited for our American Futures project and our subsequent book, Our Towns, has focused on the “local” as their guide and frame for plans and actions. In Brownsville, that eye on local seemed to us as compelling and powerful as in any other community we have seen, and maybe even more so. Sometimes local means a focus on physical assets, or geography, or demographics, or industry. In Brownsville, as we listened to citizens talk, local seemed to be mainly about culture.

The culture of Brownsville was the backdrop to their master plan for health and wellness—and many other town issues. “We are fighters. We stand by our family. We are proud. We may be poor, but we do not think of ourselves as just poor. We think of ourselves as blessed to have our families, customs, and region surrounding us.” And Rose Gowen adds in talking about outsiders’ impressions of Brownsville, “You don’t hear that on the news.”

Those traits translated into action. Brownsville is not looking or waiting for top down solutions and proclamations. Members of its community decided to: Make local-government regulations that support their goals. Get smart about seeking funding, from the government, foundations, and non-profits. Not let rebuffs from big funding stop them; take it step by step, and find corners to improve. Educate the public and brand the message: “Health and Wellness.” Become a model for success.

This kind of positive, panoramic, inclusive approach is one we’ve seen in niche initiatives and big plans in many of the towns we’ve visited. Libraries in Bend, Oregon. Arts and Entrepreneurship in Fresno. Education in Greenville. Downtowns and main streets everywhere. Workforce training and new industry in Mississippi’s Golden Triangle. The entire town of Eastport, Maine.

* * *

Through its many initiatives, the Brownsville Wellness Coalition is all about healthy food and healthy bodies.The Community Gardens program teaches gardening classes and distributes free transplants and compost. Five gardens hold nearly 200 beds.

People can buy produce from the weekly Farmer’s Market with cash or with vouchers from the federally subsidized programs like SNAP, WIC and the Farm Fresh Voucher program, especially important in this low-income town. Plans are underway through a coalition of funders to renovate an old town cannery, the Gutierrez Warehouse, into a permanent home for the Farmer’s Market. When finished, the Quonset hut plans also call for accommodating a food bank and a “kitchen incubator” with a commercial kitchen for small food businesses. And for those who can’t get to the Farmer’s Market, the Fresco Mobile Market food trucks may come to them.

The Happy Kitchen/La Cocina Alegre holds classes on nutrition, food preparation, and healthy eating.

And for the bodies, The Wellness Coalition sponsors a walking group program, the Walking Club, with motivational support and progress tracking.

An annual Challenge program organized by the city and the UTHealth School of Public Health and drawing help from local gyms, nutritionists, trainers, and other experts encourages not only weight loss, but also sustainable lifestyle changes toward better health. Nearly 7500 people participated in the 3-month program this year.

The monthly CycloBia, closes some Brownsville streets to cars and opens them to the 10,000 participating residents to walk, bike, skateboard, skate, and run.

And for the timid, who may be the most reluctant to begin, the UTHealth School of Public Health has prepared online resources, Tu Salud Ci Cuenta, where people can tiptoe into exercise and healthy eating and weight loss privately and solo. I found the stories poignant, and brave, and ended up rooting for them.

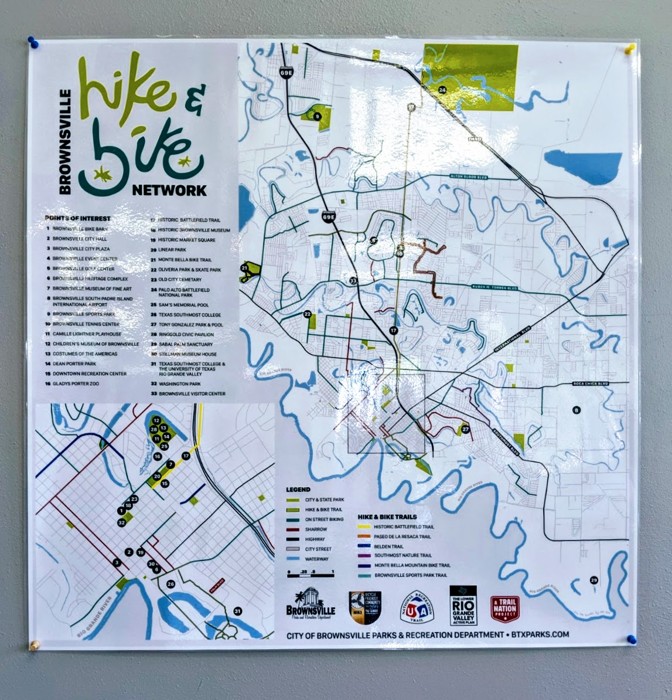

Brownsville is also part of a multi-use trail program (Bikes! Paddling! Hiking!) throughout the lower Rio Grande Valley, which will link several towns, beaches, preserves, waterways, and cultural sites over 400 plus miles, incorporating as well a dream of tourism potential.

Is any of this working? According to Joseph McCormick, the rates of obesity and diabetes have dropped about 3–4 percent in Brownsville in about the last five years.

Trails through downtown Brownsville already gives lots of folks options for daily commutes to school or work or, as in our case, a visit to 1848 Barbecue, a slow-cook BBQ named for the year Brownsville was founded. As one who spent about five years living in Austin, and got my graduate degree from the University of Texas, I feel that my Texas bona fides and palate entitle me to shout out to Abraham Avila, the chef of 1848. Yeah, lots of calories, but sitting right on a hike and bike trail, you can worry about working it off later. It’s worth it.