The public library system in Brownsville, Texas, has a long history of inventing and then reinventing itself to be of, by, and for the people. The library story began modestly at the end of the 19th century, with the personal collection of Irish-born U.S. Army Captain William Kelly, who had settled in Brownsville and become a renowned businessman, proponent of Brownsville’s first public schools, and a civic activist. His daughter Geraldine recollected later in the Brownsville Herald, “He had a very fine library, which he used continually and loved.”

In 1912, a group of Brownsville’s intellectual and high-minded women calling themselves the Learners Club started the town’s first subscription library. (Other women’s clubs have been promoters of early libraries: In 1905, the women’s club of Dodge City, Kansas, inspired some of its prominent citizens to ask Andrew Carnegie if he would support building one of his libraries in Dodge City. He did.)

A decade and a half later, the Learners Club and the city teamed up to transform the Brownsville subscription library into a public library in a larger space. It moved a few more times over the next decades, before partnering with Texas Southmost College and locating the public library on its campus. There they stayed until 1991.

Then, with the city’s support, the Brownsville public library pivoted toward its modern era.

Jerry Hedgecock, who has been with Brownsville libraries since 1993 and is now the director of the Public Information Services Department in Brownsville, described to me how the library was able to start back in the 1990s, in effect from scratch, with the driving mission to make the library a go-to destination for the residents of Brownsville. They erected a new building and ushered in new ideas and new programs.

After some early years, which Hedgecock described as, “to be honest, very boring,” they prepared to change emphasis so as to offer more services. It was all about being relevant to the community, he said: “What do the people want? What do we want?”

Library plans were farsighted; they were creative and intended to reflect the culture of the town and region; and they were executed efficiently and also patiently, adding projects piecemeal, year by year. With a line item in the municipal budget supporting them ($4.8 million in 2019), a library foundation that contributes to capital projects, and the still vital Learners Club and a Friends group pitching in, the library evolved.

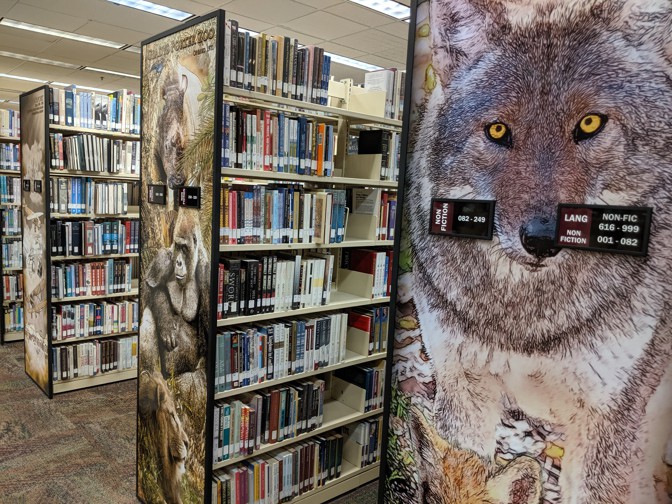

One year, old wallpaper was removed. Another year, end panels with blown-up photos of important images of the region were affixed to the rows of bookshelves. To be both efficient and personalized, the library created a graphics department to make their own artwork, with double wins of being less expensive and more Brownsville-personal than what was available from generic catalogs.

The library currently owns and makes available to users 259 computers, as online access is critical to this community. But the library’s leaders expect that as more people become able to afford their own computers, the need will ratchet down, and the library will switch some of the computer space to suit different needs.

As with every other library I visited, use of space was a top concern. (This is despite the common impression that libraries must have lots of extra space, as some reduce their holdings of physical books.) Even in Texas, where the size and scale of everything from ranches to libraries feels vast, Hedgecock says that space in the library is tight, and they pay close attention to how they use every nook and cranny.

The “maker space” holds eight 3D printers, and there are plans for laser cutters and more.

Maybe they’ll build a tool bank, suggested Hedgecock, an area that would be stocked with devices and equipment to meet the expanding skill sets of their population. Being nimble and responsive to the population and their changing needs is critical. “Without new services,” Hedgecock said, “we won’t be relevant to the community. We can’t be complacent.”

The library took over the local-government access television channel, whose studio is housed inside the building. The public was delighted, but became distracted enough by its presence that the station is now out of sight behind unmarked closed doors. There are plans to relocate the station to a newly created municipal department. I found this recording from the station of a live event presented by Texas Monthly in Brownsville this July. This magazine, where my husband, Jim, worked in its founding days in the 1970s, when we were living in Austin while I did my graduate studies at the University of Texas, takes its show on the road around Texas for live 90-minute performances of music, video, reading, and storytelling, curated by the editors. You’ll do yourself a favor to watch this one, where writer Wes Ferguson reads about his return to Brownsville.

I visited the library on an early voting day for the city election, and the place was buzzing. People were wandering in and out, having lunch at the library’s cafeteria, checking books in and out, sitting at tables reading newspapers or at computers working.

What surprised me most in the Brownsville library was the teen space. It’s called Space 14s. You get it. We’ve all heard about the children’s areas—the reading readiness, the story hours and preschool activities. From what I’ve seen, most public libraries are sophisticated with the preschoolers by now, and for many libraries, making themselves relevant to teenagers is the next step.

Brownsville is ahead of the curve on this one. Several librarians around the country told me that teens are the hardest group to attract to the library. Brownsville took this challenge head-on and worked with the Library Interiors of Texas to design its two-story teen space in the library. The themes of outer space, diversity, and technology dominate wall murals everywhere you look. Colorful, comfortable seating around workstations, at tables, and in big chairs invites hanging around. The spotlighting and the upper-level overlook struck me as opening space to easily scope out everyone and everything happening, which is how I think of preferred teenage behavior.

Hedgecock described the public opening of the new teen space, Space 14s. The crowd gathered. A curtain was drawn in front of the space and lights were down. The curtain opened; lights were brought up. As Hedgecock relives the moment when people first laid eyes on the new teen space, “It was the first time I’ve heard an audible gasp from the public at a library.”

I asked about the Brownsville library as a “second responder,” as I had heard about other libraries that had stepped up to serve their people after the riots in Ferguson, or Hurricane Sandy in New Jersey, or the shootings in Orlando. Brownsville had its own story: During the recession, one family where both parents lost jobs and couldn’t afford to run their air conditioning (which is a big deal during the summers in Brownsville), came to the library and asked if they could spend their days inside. “Of course,” was the answer. After the father got another job, and the family was able to run their air conditioners again, they sent a thank you note to the library for helping them when it mattered.

I heard another second-responder story when I visited the second, smaller, neighborhood library in Brownsville, the Southmost Library. Librarians there told me about the kids who are bused in from the nearby migrant-detention center to watch movies, eat popcorn, and drink lemonade. Jim and I were not able to go inside a detention center, but it takes no leap of imagination to guess how the kids value this field trip to the public library.