Most of this coming week we will be in northeastern Montana on the American Prairie Reserve, which is an ongoing, ambitious project aimed at returning as much as three million acres of grassland to its historic status as the most fertile and abundant habitat for wildlife in the territory that is now the United States. Tonight, on the solstice (and other holidays), we’re at an en-route stop at the Great Northern Bed and Breakfast in Chester, Montana, a very small town about which there will be more to say.

More from these sites in due course. Today’s installment is the first of several on the also-ongoing economic turnaround of Central Oregon—in particular the parts of Deschutes and Crook counties that include the cities of Bend, Redmond, and Prineville.

Their regional story is both plainer and more complicated than others we’ve seen through in our travels. It’s plain in that it is one more “decline of a natural-resources economy” saga. In that way it’s similar to what happened when the sardine-canning industry disappeared from Eastport, Maine; or when coal and chemical businesses declined around Charleston, West Virginia; or when the enormous copper mine that was the main economic reason-for-being of Ajo, Arizona, was shut down. Or what could conceivably happen to California’s Central Valley if the historic drought goes on.

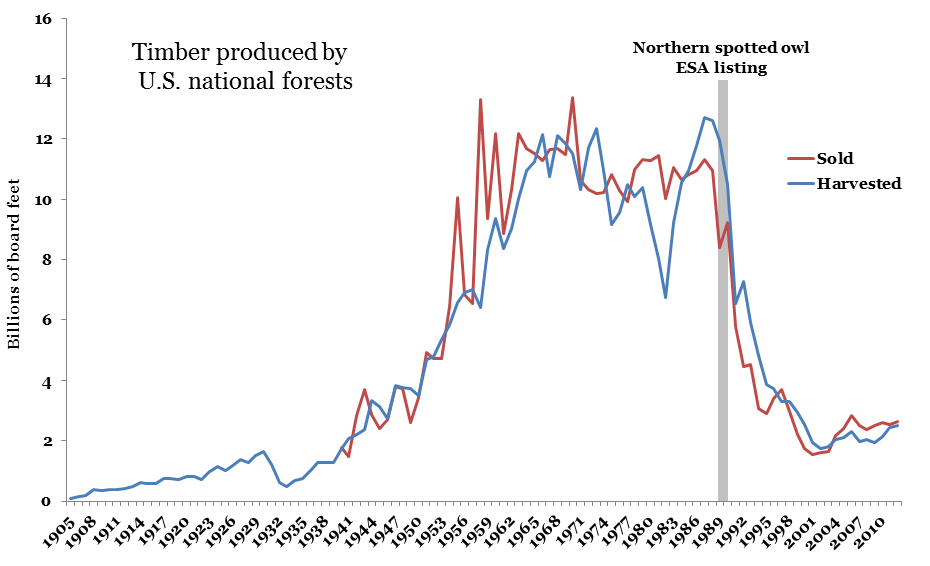

In central Oregon, the crucial natural resource was of course trees—timber from both privately owned tracts and, significantly, the national forests managed by the Forest Service and other federal lands run by the Bureau of Land Management. Loggers were in the forests, lumber workers were in the sawmills, truckers were behind the wheel of big rigs taking logs and boards to their destinations, and construction workers were on the job around the country putting wood products to use.

Traditional Extractive Industries in Decline

For reasons we’ll get into another time, it could not last. The trees ran out; the Forest Service changed its rules; the Endangered Species Act kicked in; and because of other factors the timber/lumber industry that had built the communities, created great fortunes, and employed most of the working people in Bend, Prineville, and elsewhere would not regain its former scale.

That’s the (depressingly) familiar part of the story, though with some interesting twists about long-term management of the national forests which will get to in a later installment. In its modern history, even Bend — now the largest, most prosperous, and most stylish of the cities in the area — had two episodes of severe downturn. One was in the 1980s, when it became clear that the timber industry really was gone and was not coming back.

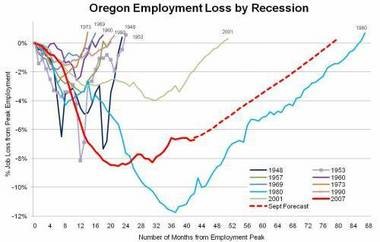

For America as a whole, the job losses after the Great Crash in 2008 were more severe than anything since the 1930s. It was different in Oregon, where the prolonged downturn of the 1980s was even worse. The chart below shows how much Oregon was an outlier. For most of the country, the post-2008 recession differed from others in that so many jobs vanished, and that they took so long to return. But for Oregon the job losses had been even greater, and the recovery even slower, in the early 1980s. The red line below shows the post-2008 employment damage in Oregon. The light blue line shows what the state suffered 25 years earlier, as the timber industry went away.

This is not to minimize the impact of the post-2008 crash in Bend and its environs. This was one of several (mainly Sunbelt) areas of the country that had been riding a construction-borne boom. When that boom ended, unemployment was as bad in Bend as in any Rust Belt trouble-spot you could name, reaching nearly 16 percent in 2009. A New York Times feature in 2009presented Bend, in economic “freefall,” as a “succinct symbol for the economic perils of ‘lifestyle destinations’ in the so-called New West, recreation-heavy communities where jobs have been heavily tilted toward construction and services and where many of the new residents were self-made exiles from California cashing in on their overpriced real estate.”

***

Six years later, everything about Bend looks flush. The real-estate vacancy rate is said to be around one percent; the city has two thriving-looking downtowns: the traditional-style one, on Bond and Wall Streets, with mainly local outlets and an ever-growing array of craft-brew operations, anchored by the 27-year-old Deschutes Brewery; and the restored Old Mill District, with a 16-screen movie theater and hotels and national-brand outlets and a river-walk recreation area where the millponds used to be.

The main local concern of the moment seems to be managing the pace of growth — both in the short term, so as to avoid a repeat of the previous real-estate bubble-and-bust, and in the longer run, to avoid a prospect that was always described to us as “becoming another Aspen.” By this they (obviously!) mean no disrespect to Aspen’s role as a music, cultural, and intellectual center, notably including The Atlantic’s own Aspen Ideas Festival that begins a week from now. Instead they were using a mountain-west shorthand of what could also be called “another Hamptons” or “another Nantucket,” a place so successful in attracting moneyed residents that the people who work for them can’t afford to live anywhere nearby.

The situation is notably different 35 miles away in Prineville. It was once a prominent city in the region, but lost out when the major railroad was routed through Bend rather than Prineville a century ago. It has had its ups and downs since then and now it is pinning significant hopes on hosting two enormous data centers, for Facebook and for Apple. (Plus an innovative approach to forestry.) Redmond, in between Bend and Prineville, has its own path, which includes an emerging role as an aerospace-technology center.

The different approaches these communities are taking, in what for all of them was once a timber-dominated region, and the reasons behind the differences, are interesting in themselves, as we’ll hope to explain in the next series of posts. But let me introduce them by mentioning one real anomaly of the region, and of how people are trying to progress.

The anomaly is: There’s no research university, or even a four-year degree-granting university, in Bend, Prineville, Redmond, or elsewhere in Central Oregon.

This is an anomaly because where you have tech-based hopes for economic growth, you almost always have a research university. The Golden Triangle of Mississippi has its challenges (and successes), but it also has Mississippi State. Sioux Falls, South Dakota has a raft of private and public institutions. The Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton triangle of Pennsylvania has been buoyed by Lehigh, Muhlenberg, and others. Greenville, South Carolina has nearby Clemson and in-town Bob Jones. And this is before we even get to Columbus, Ohio with Ohio State or Pittsburgh with Carnegie-Mellon and Pitt.

It is an anomaly that people in central Oregon are hyper-aware of, and it is part of a years-long local push to expand a branch of Oregon State University Cascades into a standalone four-year school in Bend. The proposed location for the new campus is the subject of lawsuits and local controversy (you can get an introduction from the Bend Bulletin here), but most people we spoke with expected that sooner or later the school will be built.

So how has the region gotten along without a university? In significant part through an unusually active and ambitious community college, whose vice-president told us that it was “university-esque.”

As we’ve described in reports from Maine to Mississippi to California, we’re continually re-impressed by the role of community colleges (and allied “career technical” schools) in helping cities attract and spawn industries, and in preparing students for high-wage, high-skill technical jobs.

Central Oregon Community College, or COCC, has its main campus in Bend and branches in Redmond, Prineville, and elsewhere in the region. Like other community colleges, it emphasizes an extra chance for people who couldn’t afford a four-year college—or weren’t ready for it, or were busy with children, or had other things going on in their lives. It is also like them in working closely with regional employers and entrepreneurs. Two years ago, for instance, the FAA approved sites in Oregon for tests of new UAV/drone systems. Matt McCoy, the COCC vice president for administration (and the man who said “university-esque”), told us that within a year the college had a UAV-technology program planned, staffed, and running. The healthcare industry is a major employer in Bend, and COCC has opened new health-technology programs. Its branch campus in Redmond specializes in advanced-technology manufacturing systems.

But COCC was also different from other community colleges we’ve seen, in ways that show the malleability of this educational model — and indicate how an institution responds when it’s bearing normal community college responsibilities and stretching to do more as well. Comments we heard:

• COCC is the oldest community college in Oregon, founded in 1949, and one that has been exceptionally stable. It has had only five presidents in its 65-plus years of existence. Faculty and staff, once recruited, tend to stay.

• It has exceptional support from its community, including financial support. A local family donated the spectacular tract of land on Awbrey Butte where the main campus is now located. Since 1955, local donors have supported a COCC Foundation, which gives out more than $1 million a year in scholarships. Usually four-year schools crowd out community colleges for “naming gifts,” the large-scale contributions for buildings or scholarships named for the donor. COCC has done well with them. In 2009, during the worst of the recession, voters approved a big new bond for COCC. The resulting construction put hundreds of local people to work.

• COCC has created what looks like a campus, even though like most community colleges it is mainly a commuter school. (A new 330-bed dormitoryis opening this fall, part of a movement of community colleges to attract some out-of-region students by offering dorm space.)

“When we say we are a ‘community college,’ we really mean that we are for and of this community,” McCoy, who has been at the college for 17 years, told us. “We feel an obligation to help it towards a future of equitable, balanced growth.” Yes, you can hear this sort of thing anywhere. But as in several other communities that had a productive and respectful relationship with their community colleges, we got the feeling in Bend that this was more than just talk.

Why does this story matter outside central Oregon? It’s one more reminder of the ongoing but under-publicized adaptability of grizzled American institutions. Next up: more on the varied paths these three timber-zone cities are taking in the post-timber era.