In this month’s magazine and in some previous posts plus a Marketplace segment with Kai Ryssdal, I’ve emphasized the importance of civic “stories.” These are the shared public understandings, some closer to historical accuracy than others, that convey a community’s sense of what makes it unusual, what successes and struggles have brought it to today, and what options are best for tomorrow.

To call these understandings stories, or even myths, doesn’t mean that they are fictitious by either accident or design. Instead it emphasizes the importance of their narrative shape: past, present, future; cause and character leading to effect.

At every level of human existence — individual, family, community, nation — the idea of causation and sequence matters. Every American knows examples that deal with our national ideals, myth, or American dream. Since Japan has been in the news recently, I’ll mention two academic studies of its national self-concept: Carol Gluck’s Japan’s Modern Myths and the similar-sounding but quite different Japan’s Modern Myth by Roy Andrew Miller, both worth reading.

An important aspect of any such narrative is the turning point. This is the moment of decision when things go right or wrong. To use the Eastport example: the handful of people who have stuck it out there believe that they are in the middle of such a turning point: either they will invent new businesses for the town or they will see it wither away.

In upcoming items I’ll have more to say about the how and why of turning points for Burlington, Vermont (when battling young mayor Bernie Sanders took charge) and Sioux Falls, South Dakota (when the state decided to turn itself into a financial processing center. And for a 2013 update on some of its financial strategies, see this.) But for now let’s go back to Redlands, California, and the importance of how it understands its past.

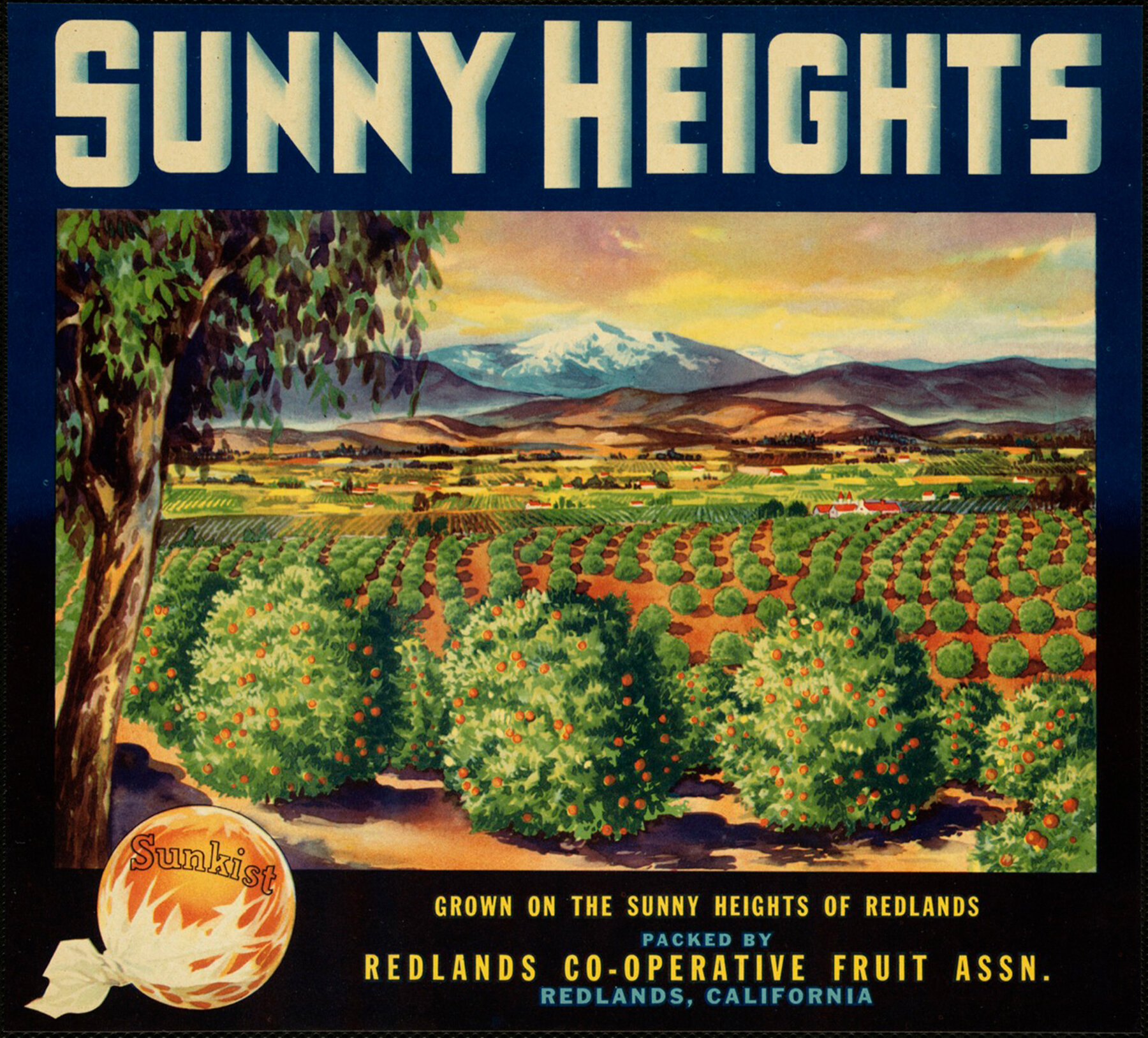

Like many other Sunbelt areas, this part of California grew during several nationwide migration surges: the late 1800s, when people came from the East and the Midwest for warmer climates, cheaper land, and better growing conditions (Redlands was incorporated in 1888); the teens and 1920s, when the citrus-growing industry dominated this part of inland Southern California and Redlands was connected to Los Angeles, 70 miles away, by the “Red Car” electric railroad; the Dust Bowl and Depression era; and of course the post-WWII California Dream era, when millions of people (including my parents, from Pennsylvania) came for the fresh start in the sun.

That’s the common Sunbelt/California story. “In the 1880s cities were growing everywhere around here,” Nathan Gonzales, the city’s archivist, told us. “The railroads had rate wars, and land was going on the cheap.” He said it was a remarkable confluence of technologies that came together to produce this Southern California boom. “Think of what had to happen at the same time: railroads all the way to the west coast, and ice-making equipment to preserve fruit for cross-country shipment, and grading and packing equipment to handle large volumes of fruit.”

The different version understood in Redlands is that it looks, feels, and acts different from a lot of other LA Basin sprawl-suburbs because:

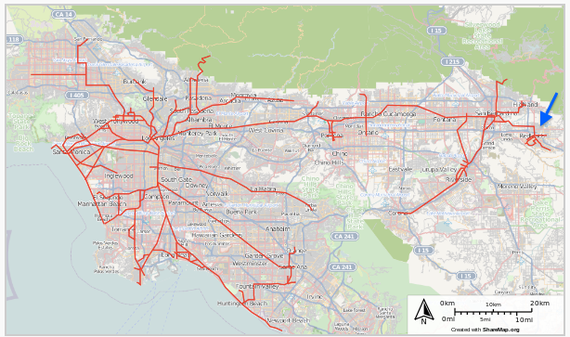

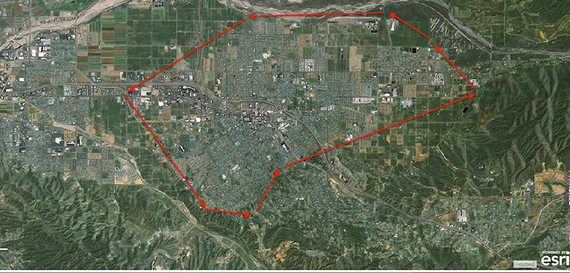

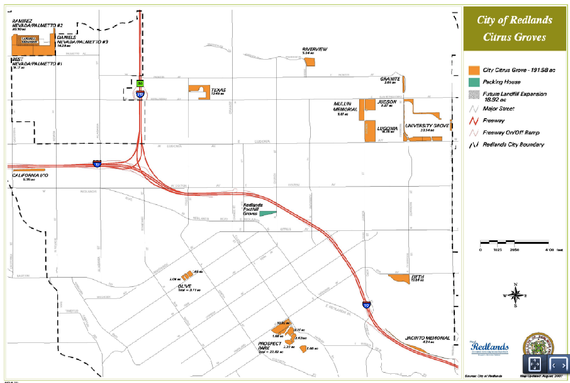

- It is still physically separate — the last city in the LA/San Bernardino basin before sizable mountains on the east, a usually dry river bed (“the wash”) and more mountains on the north, canyon land on the south, and a not-yet-entirely sprawl-developed buffer to the west. The map above aerial view below give the main idea. (The red lines are not the actual city limits but for practical purposes are its extent.)

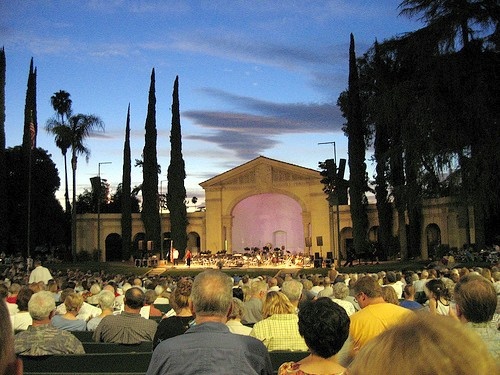

- It remembers its founders who made long-term investments in the city’s physical and natural heritage. The easiest way to explain this is by analogy with Central Park in New York. If Central Park didn’t exist, you couldn’t create it now — and all sane people give thanks to their 19th century New York forebears who had the vision to make it happen. Redlands is by comparison a tiny place, but people there have a similar view of the forebears who created: Prospect Park, a substantial undeveloped area in the middle of a residential zone; or the Redlands Bowl, set up in the 1920s as a free outdoor concert amphitheater for a town that was just getting going; or the Smiley Library, created by twin-brother Quakers from New York, Alfred and Albert Smiley; or the University chapel; or many others other aspects of the city beautiful.

- Its economy was originally based on oranges, and as the groves have given way to development it has responded in two ways: by preserving as many as it can, as a public good, and by pushing the heritage in every other way.

I said that this civic story involved turning points, so what were they? In the prevailing public narrative they included both good examples to learn from, and bad ones to be avoided.

Positive: The foresight of the 19th century founders, who provided the fledgling city with water (in a way I’ll describe another day), parks, a library, schools, broad avenues, big trees. Moral: Infrastructure and “civic culture” are part of each generation’s duty to uphold.

Positive: free public concert and lecture series over the past century, at the university and the Redlands Bowl. Moral: A town needs to be more than shopping malls.

Positive: “Measure O,” the first tax-raising initiative passed in California after Prop 13, in which the city voted an extra levy upon itself to buy and preserve open spaces, including parks, wildland, and — significantly — orange groves. It now owns some 16 groves totaling more than 200 acres through the city, including some in the visible center of town. About 2,500 acres of citrus groves remain in production locally.

Moral: Public steps in the public interest.

Positive: Slower-growth housing initiatives over the past generation, which spared Redlands much of the sub-prime devastation that affected many nearby cities. “We had only about 500 permits per year,” the young mayor of Redlands, Pete Aguilar, told us. “That meant that the huge 2003-2008 boom in housing, which led to disasters in so many other places, didn’t happen here. We’re not like these other cities that had such a large stock of new housing, which turned into the problem.” Moral: let’s take the long view.

And there were some negative lessons too, which we’ll go into further another time. But in summary:

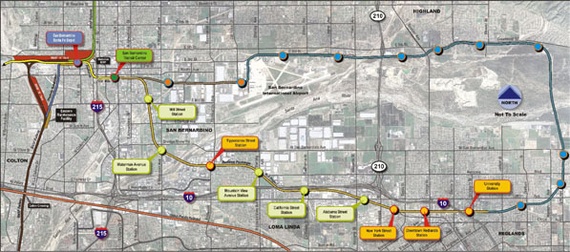

Negative: The tragedy of the railroads. A century ago, they connected Southern California; then they gave way to cars. This is a drama on a bigger scale than Redlands alone, but the city is playing its part by investing in a new rail connection to Los Angeles and the rest of the area. Moral: Bring mass transit back.

Negative: The disaster of the mall. A city trying to redevelop its downtown has a huge 70s-brutalist abandoned structure right in the middle of the shopping area. Moral: Don’t do this again. (Plus, it’s owned by out-of-town interests.)

Negative: the tragedy of Smiley Heights. The one “public” area of the city that was not preserved was a hillside area once owned by the Smiley brothers and now called Smiley Heights. It looked this way a century ago, and now is covered by McMansions. Moral: You have only one chance to keep scenic areas from being subdivided.

Negative: the “doughnut hole.” This is too complicated to explain but involves the anomalous growth of a huge big-box mall area, which drains money from local merchants but from which the city derives no tax revenue. Moral: You can’t be simply “anti-growth” but need to think carefully about phased development.

And the overall moral for now: it’s a big, complicated country, and the stories we tell ourselves matter more than we think. More to come.