Introduction: Today the New York Times has a storyby me about the reporting trip my husband and I have been taking to smaller communities across the country that have been coping with economic, political, or environmental challenges. In many towns I have found interesting and impressive schools to learn about, often at odds with the prevailing narrative of public schools failing across the board.

Some previous examples: the Sustainability Academy in Burlington, Vermont; the Grove School in Redlands California; the Shead School in Eastport, Maine; several English immersion schools in Sioux Falls, South Dakota; the Governor’s School for the Arts and Humanities in Greenville, South Carolina; the A.J. Whittenberg Elementary School for Engineering, also in Greenville; and (by my husband) the Camden County High School near St. Marys, Georgia. This report is about one more of these schools, in Columbus, Mississippi.

One warm and misty May morning in Columbus, Mississippi, the lobby of the classroom building at the Mississippi School for Mathematics and Science (MSMS) was full of teen-agers milling about, waiting for morning classes to begin.

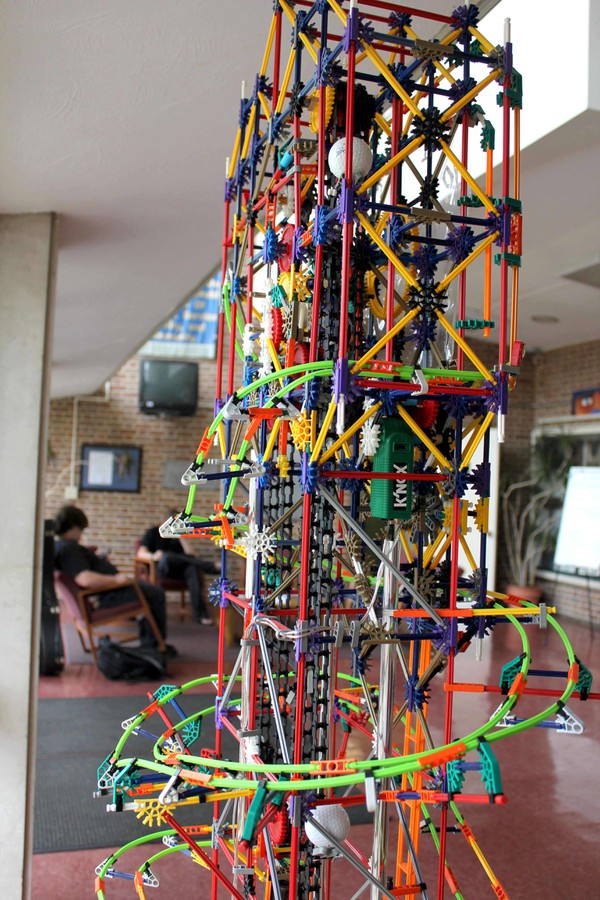

In one corner of the glassy space was a grandfather clock, probably about 8 feet tall, constructed by one of the students out of brightly colored plastic pieces. (Right.) On the hour, a little white ball would roll down a chute, tripping levers to ring a small chime. Upstairs in one of the science rooms was a 3-D printer, a rough-and-ready contraption that, with a little more luck, is approaching the final stages of actually printing something. Another of the students, a senior, had made it himself. I recognized several other students whom I had seen performing in an after-school stage production, one dressed as Eco-Man in blue and green tights, cape, and mask.

MSMS is a public boarding school in Columbus, occupying a few of the more modest buildings on the grounds of the elegant Mississippi University for Women, is called “The W”. The men who have enrolled at The W since it became co-ed, say they always have a time explaining themselves to those not in the know.

/media/img/posts/2014/05/MSMS4/original.png)

Columbus is a small town of about 25,000 people midway down the state, near the border with Alabama. Many of the buildings on the main streets are under renovation, and some of the antebellum homes are still occupied by the families who built them. The 228 students at MSMS this year, all juniors and seniors, come from all over the state to spend their last two years of high school studying accelerated sciences, math, and computer courses, as well as a rich selection of arts and humanities.

When I visited MSMS recently, I asked some of the students what they liked about their school and how it was different from the schools they came from.

A black girl from a nearby town, even smaller than Columbus, said that her high school was all black, and she appreciated being in a diverse environment. A white girl from a larger town in the south of the state said that her school, a private school, had been all white, and she appreciated being in a diverse environment. “My roommate is from India,” she said, “I had never met someone from India before.” A black boy from Columbus said his high school had been somewhat mixed, but it was really all about football. He said he appreciated being in a place where football didn’t dominate everything. And they all talked about opportunity, opportunity, opportunity.

At MSMS, 27 percent of the students are black; 18 percent are Asian; 11 percent are mixed; 44 percent are white. Students find their way here from all over Mississippi, from big towns like Hattiesburg and small ones you can barely find on a map. The admissions recruiters fan out all over the state, working particularly hard in the impoverished delta region. While I heard that sometimes their reception is enthusiastic, other times—when there can be dismay at draining some of the best and brightest from a school or when there is a perception that their own school isn’t good enough—the reception is less welcoming.

Selling the school to Mississippi parents—even a school that regularly sends state champion teams to national science fairs and scoops up half the writing awards in the state—can sometimes be hard. Several students told me that their moms were scared, or nervous, or didn’t want them to go away. And the students themselves said they had to abandon extracurriculars that were important to them at home, but weren’t available at MSMS. But those were always a warm-up to their feelings now: “I am so happy to be here. I have so many opportunities. I am so fortunate.”

/media/img/posts/2014/05/MSMS5/original.png)

I set out to visit some of the classes. A dozen or so students in the robotics class were testing the robots they built for an upcoming national competition. There were 3 robot missions: search-and-rescue; a mock sumo-wrestling match; and a bell lift, where the robot scooped up a bell and delivered it to a destination.

There were 8 boys and one girl in the robotics class. This was surprising to me, especially considering the (also surprising) fact that the MSMS enrollment is 57 percent girls and 43 percent boys. I heard various interpretations of these two gender discrepancies. Two that made sense to me were first, that robotics class is primarily about programming, and boys prefer programming while girls prefer making apps. And second, the culture of football in Mississippi is so strong that it is difficult to draw boys away in the middle of their high school years to even a school as good as MSMS, which does not have a football program.

/media/img/posts/2014/05/columbialead/original.png)

The humanities classes at MSMS were described as the school’s “secret weapon,” by Wade Leonard, the school’s public relations coordinator and an MSMS graduate himself. I would agree. In Thomas Easterling’s English class, they were reading a Bharati Mukherjee short story. The class, busy being teenagers, was in high spirits. “Curb your enthusiasm!” Easterling had to call out at one point. There were about 7 girls and twice as many boys in the class. Most of the students were taking notes on laptops; one was multitasking his laptop with his phone. An Indian girl in the class was quietly correcting pronunciation of Indian names. They were rapt at the life story of Mukherjee, and—adolescents that they are—were comfortable and attentive in a discussion of self discovery. Easterling drew them in to talking about whether immigrant status accelerated self discovery. “Abso-stinking-lutely!” was one hearty response that pretty much revealed the energy and engagement of the class.

/media/img/posts/2014/05/MSMS9/original.png)

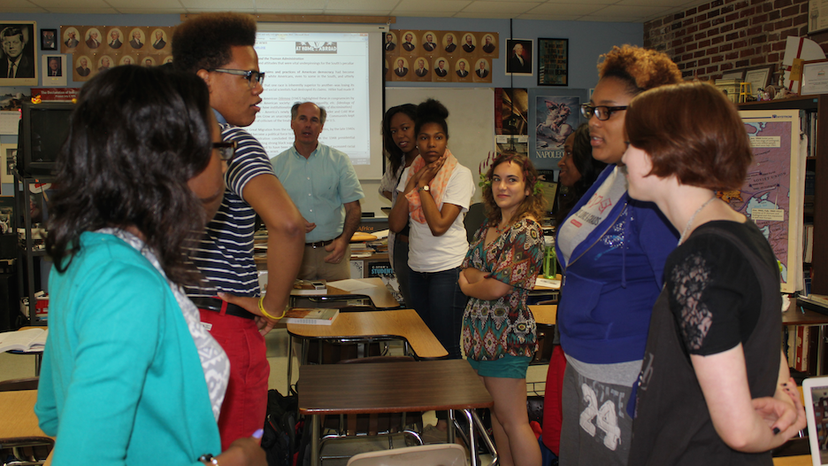

History teacher Chuck Yarborough was having a busy week. He was teaching his African-American history class, which he choreographed like a stage production—a short bit of a video, a discussion of not only the civil rights history of the times, but making it real and relevant to these Mississippi kids, whose own lives and those of their parents and grandparents were wholly involved. Then he had the students up and moving, debating sides of the question of blacks fighting in the WWII military. He organized a community-wide performance in the town’s black cemetery commemorating the May 8 Mississippi Emancipation Day. There is no way his students could wind up his class, I believe, without a deep sense of the history of race in their own lives and communities.

MSMS was founded in 1987, shortly after the administration of the educationally progressive Governor William Winter, who introduced sweeping reforms in 1982, including among other things, mandating kindergarten for all students and compulsory attendance until age 16. It was the fourth such specialized secondary school for math and science to be established in the US. Despite its veteran status, MSMS remains modestly funded, primarily by state funds, with some additional foundation and private support. It is not nearly as fancy or well-endowed as, for example, the impressive Governor’s School for Arts and Humanities in Greenville SC, which I wrote about here. So far, it seems to make up in heart what it lacks in funding. The administration fights for more and is bittersweetly aware that there “nothing wrong that money can’t fix” about the school.

So where is it headed? How big can the dreams of the teachers, the staff, and the students of MSMS be?

From what I saw, they can all be big, very big. The faculty must have something close to their dream jobs already. They report better than average teacher salaries, advanced degrees (all have at least a masters degree), long tenures, professional development opportunities, and students selected for their work ethic. The administration and staff use words like mission and passion and a vision for improving not only the lives of each and every student, but reaching far into the state of Mississippi. The state of Mississippi seems to outline the frame of most conversations I had at MSMS; it is heavy with its history and ongoing struggles, yet it is beloved as Home.

And the students’ big dreams? Here is one, from the same young man who is building his own 3-D printer (and who, incidentally, won a scholarship from the Gates Millennium Scholars Program, which will give him a ride through Harvey Mudd). He said he would like to get cheap 3-D printers to resource-deprived third world countries, which could help them make what they need to realize the products they imagine. And then he wants to return to this part of Mississippi to build his own engineering company, which would also help address the education problems in Mississippi. “I am very blessed. I’ll never forget where I am from. I see the struggle,” he says, also adding that it is about more than football.

No one is discouraging students like this from their big dreams. In that Mississippi is doing something very right.

/media/img/posts/2014/05/MSMS12/original.png)