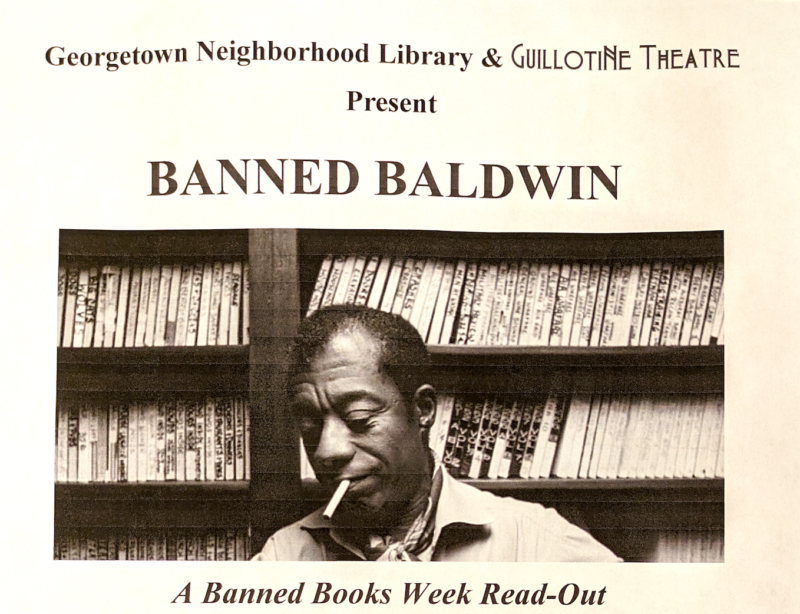

Through the coming year, the public library system here in Washington DC is hosting a Centennial Celebration of the life and works of James Baldwin, born on August 2, 1924. This week, libraries in DC are having events as part the nationally designated Banned Books Week. One of our local libraries opened the week with a reading from James Baldwin’s works.

I had heard about banned books readings at other libraries across the country and decided to see one for myself.

The Georgetown neighborhood library in Washington is in a classic, elegant Georgian-style building, on an intersection where commercial meets residential. It’s a toney locale, but each time you go inside, the diverse collection of customers reminds you that this is a public library first, and located in Georgetown second. During the winter, when the library had to close for emergencies, I read a sign posted on the door listing places where people who they knew spent their days there, might go to seek shelter from the cold.

I had no idea what to expect from the book reading. Here is what I found.

I joined a few dozen people in the library’s basement common room, a space I knew well from community yoga practices. It was a tribute to Baldwin and probably also to national struggles over book-banning, I thought, that on a perfect Indian-summer Sunday afternoon, so many souls chose to sit in a basement, on stackable chairs, under fluorescent lights, and listen to other people read out loud.

At a few long folding tables, eight people–about half of them Black, half white, half women, half men–sat ready to read from a selection of Baldwin books that had been subject to bans. These included novels, nonfiction, and an unpublished work that was the basis for the documentary, I Am Not Your Negro.

Then the magic started. It turned out that these were not just anyone reading the selections. These were actors from DC’s Guillotine Theatre, whose mission is to “bring classic literature—and plays about classic literature—out of the library and onto the stage.”

Well, on this day, the library was their stage. In this windowless room, standing at a portable podium, the readers easily transported rapt listeners up from the basement into a mental space as grand as the theaters at the Kennedy Center, a walkable distance away.

Patricia Williams Dugueye, whom you can see at her IMDb site here, read passages from Baldwin’s autobiographical novel Go Tell it on the Mountain, of a young Florence recalling her mother’s stories about the rape of a 16-year-old neighborhood Black girl.

Dugueye startled me right out of my seat she when cried out interjections from Baldwin’s text and burst into a capella song. I thought immediately of Barack Obama launching seamlessly into Amazing Grace during the memorial following the massacre at the Mother Emanuel AME church in Charleston in 2015.

The several readings – no, performances – ended with one by James Lewis, whose IMDb site you can see here. It was easy to imagine that James Baldwin himself would have selected James Lewis to read. Lewis is an imposing man with a stentorian but measured voice. He read very brief but stunning selections from I Am Not Your Negro.

After the reading, I asked James Lewis and Catherine Aselford, the artistic director of the Guillotine Theatre and veteran organizer of this and many such read-outs, what these readings meant, what were their impacts, especially as an answer to the publicity of current vitriolic book challenges and demonstrations. Did read-outs offer balance in the ecosphere of book banning? Counterpoint to point?

Lewis said what we all knew and witnessed, that this was kind of preaching to the choir, and if only those on the other side could come and listen..it might, probably not, but might change some minds.

I would add a few things that such readings might mean:

- Announcing for the record, that while some people are attacking books, others are celebrating them. The action of read-outs amplifies the voice of the choir that Lewis says he’s preaching to.

- Saying words out loud can have consequences. Some words actually do carry official power. When officiates say: I hereby pronounce you.. When juries say: We find the defendant.. When authorities in a government say: We proclaim this day.. or We declare a state of emergency..

While a public reading does not carry authority, it can carry a powerful message, if not sometimes even consequences. - The cost of not performing these readings, of not speaking out loud would create a profound silence.

This is what I learned when banned books were read out loud.