A century and a half ago, a widow in South Carolina’s “Upcountry” wished to have a town built on the plantation her husband owned. His family name was Walker, so she thought “Walkerville” would be fitting. She also wished for people to settle in, or at least visit, the would-be town. So, she offered the Chester and Cheraw Railroad a spit of land to lay a line, which they did. The Walkers’ daughter had married a doctor, who owned a large lawn next to the railroad tracks. His family name was Fort. So remarkable, and memorable, that upon approach, the conductor would holler “Everybody off for Fort’s Lawn!”

That name stuck, the railroads expanded, and the town of Fort Lawn was established in 1887.

The rise of the town that some 900 people call home today began in the early 1950s with the boom of South Carolina’s textile industry. Consequently, its decline came with the industry’s bust in the area in the early 2000s.

But in 2017, a new, different kind of rise began in Fort Lawn. Buoyed before by a swell of economic development, today’s Fort Lawn is being lifted by community development. To see it for ourselves, my fiancée and Our Towns colleague, Michelle Ellia, and I headed to Main Street, Fort Lawn during a reporting trip through the Carolinas last summer.

A Community Center at the Center of a Community’s Progress

Fort Lawn’s Main Street is not the metonym “main street” one might imagine in small-town, rural America. Rather than rows of storefronts tucked behind sidewalks with ample parking in front where residents come to eat, to recreate, to be somewhere other than home that helps give a sense of the town’s identity, houses line each side of the road. But past the houses, near the very end of Main Street, you’ll find, as we did, the place where townsfolk congregate – the heart of the community’s revival, the many-piston engine driving today’s progress: the Fort Lawn Community Center.

The building, once a schoolhouse, had sat vacant for decades until a group of residents gathered to develop plans for a renovation in the 1990s. By 2001, the Center opened with a wish list of events and programming that could happen there, including in education, health and wellness, recreation, and the arts.

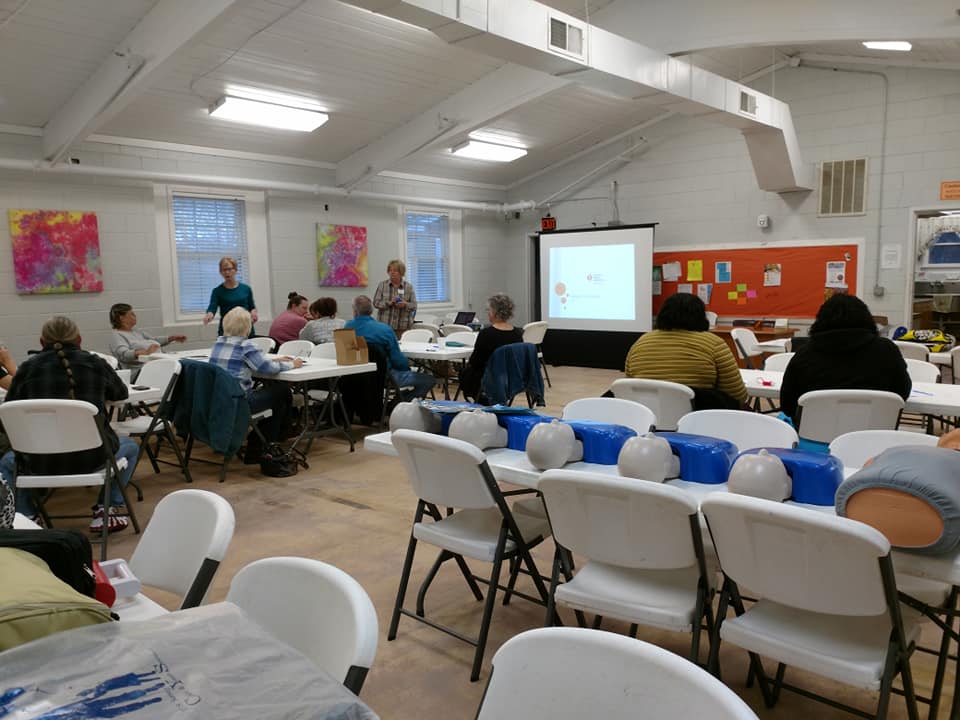

Fast-forward to January 2017. Another renewal effort had begun in earnest. Two critical parties collaborated: Three dozen residents throughout the region, and the leadership at the Arras Foundation, a nearby health legacy foundation in service to the health and wellness of area residents.

The Foundation had learned about Community Heart & Soul, a resident-driven process to help guide community development. The Arras team committed funding to bring Community Heart & Soul to both Fort Lawn and nearby Kershaw. (Community Heart & Soul is a partner and supporter of Our Towns reporting.) The process formally launched in March 2018, led out of the Fort Lawn Community Center, and included the entire 29714 ZIP code, a population of about 3,300.

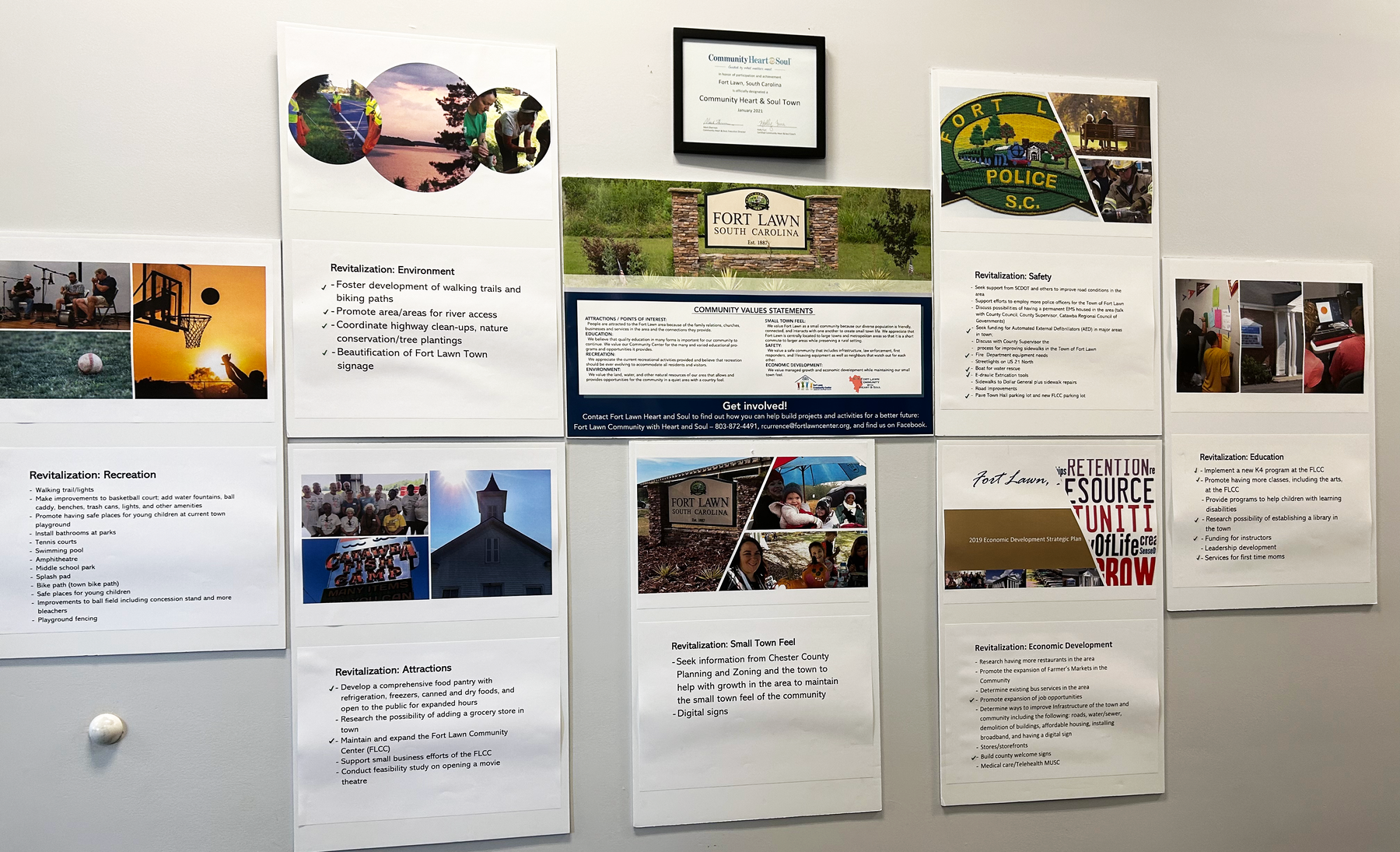

The group of volunteers surveyed some 640 residents in-person – at community events, at the town hall, at festivals, in church parking lots – virtually anywhere they could amass an audience, including over 1,200 interviews over the phone or via Zoom, to learn what mattered most to residents. What they heard yielded the community’s “Value Statements,” a blueprint of what work to continue, what to develop, and what to aspire to.

Turning Talk to Action

Michelle and I first met Mick Harrington in front of the Community Center. Mick greeted us with a handshake and a hello and, likely after we detected the absence of a South Carolina drawl, quickly shared he wasn’t from around there.

Mick had moved to Fort Lawn from California in 1999, and eight years later made his way to the Community Center, where he volunteers, and joined the Heart & Soul team. “I retired in 2016, and after a year of sitting on the couch, I needed something to do,” he told us. “As Libby (the executive director of the Fort Lawn Community Center) would put it, I lived in a silo – I was just pretty much in my own neighborhood, my little world. So, I came down here and saw the ‘volunteers needed’ sign, and walked in the door. It was the best blessing.”

Knowing Libby Sweatt-Lambert, the silo-busting, frenetically-yet-coolly-always-on-the-move leader is critical to knowing the story of the town’s renaissance.

Libby had built a career across the Carolinas working in the human services field. Energetic and persistent, Libby had served in a role for 12 years where her predecessors lasted just two. But at 50, just six weeks into retirement, she’d grown restless.

That eventually led her, about 10 years ago, to the Community Center, where, on a warm, late-August morning last year, Libby guided us through the center complex.

Just inside the main building, a poster of Fort Lawn’s Community Heart & Soul Value Statements – the results of the stories gathered during the Heart & Soul process – greets visitors. The Statements focus on: Attractions/Points of Interest; Economic Development; Education; Environment; Recreation; Small-Town Feel; and Safety.

At first glance, one might wonder: What town doesn’t care about education? About safety? About…?

But the process helps residents of any town move from the general to the specific. Throughout the 29714 ZIP code, residents declared: “We believe that quality education in many forms is important for our community to continue. We value our Community Center for the many and varied educational programs and opportunities it provides.”

With school districts consolidating over the years, residents identified the pulse of education palpitating locally in the Community Center.

The process also helps guide the how, turning ideas to action items. In this case: Implement a new K4 program; promote having more classes, including the arts; and provide services for first-time moms – all at the Fort Lawn Community Center.

Across the seven areas the community chose to focus on, residents identified 51 actionable goals. Some goals call for research or feasibility studies. Others are more in the spirit of ‘Let’s do this! And soon!’. They range from the practical (install playground fencing), to the more ambitious (have an amphitheater! a pool!), to vital (“Develop a comprehensive food pantry with refrigeration, freezers, canned and dry foods, and open to the public for expanded hours;” and, “Seek funding for Automated External Defibrillators [AEDs] in major areas in town”).

When we visited in August, we saw a food pantry replete with dry goods stacked on shelves and a refrigerator and freezer packed with perishables. When I recently re-connected with Libby, she told me that just days before our call she’d submitted a grant request to help expand their efforts to become “the food hub for the county.” Just that morning dozens of pallets of goods had already arrived, and had already been distributed to assistance providers in nearby communities, including Great Falls, a town less than 10 miles to the south that’s recently begun the Heart & Soul process.

‘What was their greatest concern around safety?‘

During that August trip, we followed suggestions of area residents, including having lunch at the Wagon Wheel. People we talked to before arriving told us we had to go there, had to have the fried squash, and would not leave hungry. So we did, and did (delicious!) and did not (stuffed!). Tables were only empty when being bussed, and residents streamed through steadily to greet Libby, then introduce themselves to us. The police chief (one of just two officers the town has). A pastor (who’s also an auctioneer). Friends (Hello! Are you coming to the game tonight?). Colleagues (how’s the planning for the Fall Festival coming?). And the restaurant’s second-generation owner (who immigrated with her parents from Greece in the 1970s).

Earlier along our tour, we had discussed safety – one of the areas of interest the Heart & Soul process highlighted. We’d learned about a pilot study for a citizen police academy that Community Center volunteers participated in, and residents’ increased involvement in neighborhood watches, among other initiatives.

“But what was their greatest concern around safety?” I asked at the lunch table.

“We do not have an ambulance stationed in this entire ZIP code,” Libby told me.

She explained that a 911 call made in the area most often dispatches an ambulance from Chester, nearly 20 miles to the west. Two Community Center volunteers at our table shared that they had lost loved ones before an ambulance arrived. Would fewer miles to go, fewer minutes to count before receiving a response made a difference? We don’t know. But that it is about a half-hour drive from Chester to Fort Lawn remains front of mind.

As a stop-gap measure, Libby secured funding from South Carolina’s Capital Project Sales Tax, or “Penny Tax” for AEDs, which she now has in both buildings at the Fort Lawn Community Center, and several more have been installed in other high-traffic buildings through the area. Her entire staff, along with two dozen residents, have all received training on how to use them, and how to perform CPR.

Progress is evident in the 29714 ZIP code

Back at the Fort Lawn Community Center in August 2022, Michelle and I saw 11 green checkmarks on the poster of goals indicating what residents had accomplished since they transitioned from generating ideas to taking action in late-2020. Now in February 2023, there are 18. Folks in Fort Lawn admit there’s still a lot left to do, but from the food pantry to the AEDs, from organized litter clean-ups to improved access to the river, the momentum continues to build.

“Our county council members will call and say, ‘Hey, Libby, who’s somebody that worked on Heart & Soul that might be good for this committee?’ It’s great that county council members have recognized the value of this program.”

She added that there had been some attempts before that “didn’t pan out.”

“We had a whole lot of naysayers. But folks are now recognizing, ‘Hey! This is this is a good thing that happened with this Heart & Soul project!’,” adding that now whether a call for assistance comes from local government or a fellow resident in need, “people come through.”

Seeing the ‘there’ there

Before we visited Fort Lawn, some warned us that there was no there there – shorthand for the absence of that Americana Main Street core. There may not be rows of retail running along Main Street, but we did find a lot of activity and energy, with most of it flowing through and out of the 10,000 square feet of the Community Center.

Like:

– The South Carolina First Steps Pre-K and kindergarten (the only one in the area, which increased its enrollment from 12 to 15 since we visited with ambitions to admit 20 kids soon).

– Senior meals (serving nearly 20 a day, Mondays through Fridays).

– Art classes through the Art of Community Rural South Carolina project.

– A physical therapy business leasing space (so that residents don’t have to commute to receive services).

– Assistance offered to residents in need of help with housing and utility costs.

– The homelessness prevention program (for which Libby told me she had just teamed up with Mike Vaughn, a member of the Great Falls Heart & Soul Team, to conduct a Point-In-Time Count).

And like, and like, and like.

I’d caught up recently, too, with Noel Nunnery, a quiet 20-something-wearer-of-many-hats-at-the-Community-Center (actual job title: administrative assistant) we’d met when we were there. I asked the Fort Lawn native what she thought to be the most encouraging thing and the most challenging thing at the moment based on her five years of experience with the Community Center.

“Encouraging? Growth – all the programs we’ve been adding to the center,” she told me. “Challenging? Maybe not having enough space. Our closets are slammed full.”

I asked what the center’s plans are. Both she and Libby told me to stay tuned. I plan to, and would bet the next I find myself on Fort Lawn’s Main Street, I’d find even more there there than I found before.