All stories about local-journalism struggles are alike. Each story of local-journalism renewal involves discoveries and innovations of its own. This is an account of a surprising and instructive story of local-journalism revival in the sparsely populated farmland of eastern South Dakota. It starts with the demise of two newspapers, the De Smet News and the Lake Preston Times. It ends — or, continues — with the birth of a new publication, the Kingsbury Journal.

For more than a century, from before the time South Dakota became a state, two small farming communities in the “Glacial Lakes” region of the Dakotas each had a newspaper. The titles and ownership structures changed over the decades, but by the onset of the pandemic era last year, both the De Smet News and the Lake Preston Times were owned and edited by Dale Blegen, who had been running the papers for more than 40 years. De Smet has a population of just over 1,000; Lake Preston is somewhat smaller. They’re both in rural Kingsbury County, which has about 5,300 people total.

(Does the name De Smet ring a bell? That may be because it was one of the home cities of Laura Ingalls Wilder, and the setting of some of her Little House books. The city now features an Ingalls town house, prairie homestead, annual pageant, and other commemorations.)

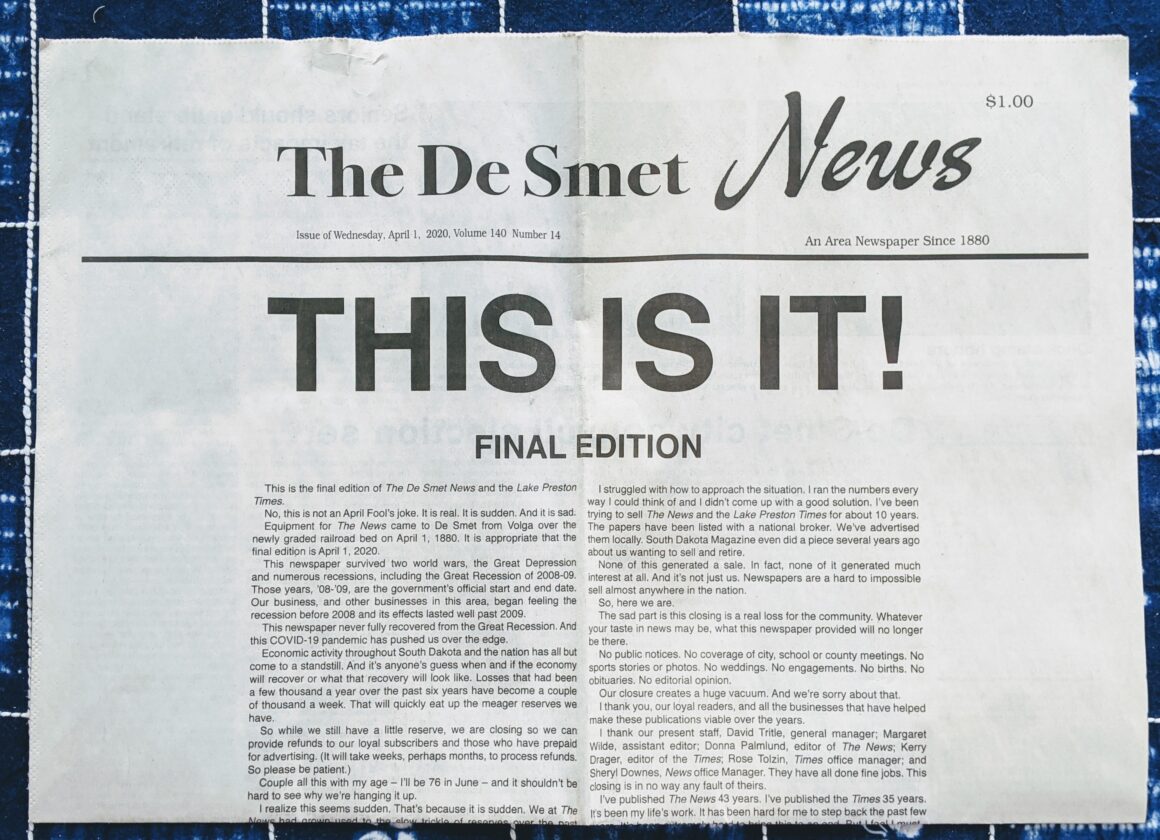

But when advertising suddenly evaporated last year for publications large and small across the country, and local businesses closed down in South Dakota as elsewhere, Dale Blegen announced that the end had come for his publications. In a banner headline for the April 1, 2020 editions of both papers, he declared: THIS IS IT. The sub-head was, FINAL EDITION. Here is the way that issue looked:

Part of this was human cycles-of-life. Blegen was only the third person to run the papers since their founding in the 1880s. He started in his early 30s and had reached his late 70s. Putting the weekly papers out had become a treadmill. An issue would come out on a Wednesday–and pretty soon, it was Wednesday again.

But the larger forces were of course the business pressures over the past generation on journalism in general, and local print publications in particular. Local merchants had other places to advertise; customers had other ways to spend their time; people had grown accustomed to the idea that news, like network TV programs, should come to them “for free.”

As mentioned in a previous post, immediately after the THIS IS IT! journalistic shutdown, a local business owner and entrepreneur named Tim Aughenbaugh produced a YouTube video about the threat that their communities would become a “news desert.” Aughenbaugh had grown up on a farm in the area, had worked with a number of tech-oriented companies, and had headed the nonprofit De Smet Development Corporation for many years. His video distilled the predicament local papers were in, and proposed a way out for his community.

Here’s the video again (below), a remarkably comprehensive survey of local journalism as a whole–remarkable in that it was produced not at some journalism school or research center but by a group of local small-town citizens figuring out in real time what they could do after they became a “news desert” when their papers disappeared.

So far the story is familiar. The surprise is what came after that, in two aspects. They are: what the communities realized, and what they did.

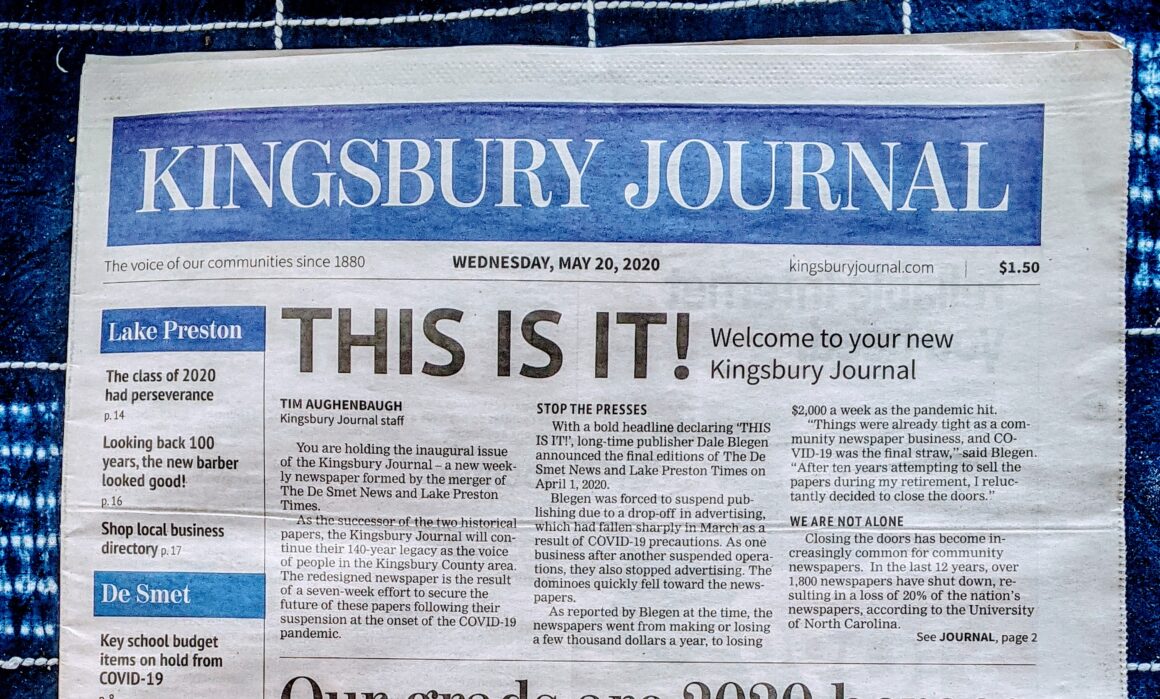

What they realized was a very specific sense of how much they stood to lose if the local papers permanently went away. What they did was come up with an unconventional approach to sustaining a new, printed alternative that would span the communities, the Kingsbury Journal.

What they realized: “People thought about the things they would miss,” Mary Rockino, a contributor to the paper who lives in nearby Lake Preston, told us last month. During a several-day visit to De Smet, Deb Fallows and I talked with her and other members of the paid and volunteer staff of the reborn Kingsbury Journal, in the downtown building that had previously been home of the De Smet News.

“You can’t have a town without a paper,” Rockino said. One of her colleagues said, “It was practical things. People said they missed graduations, births, deaths, weddings. They needed a place to go to know what was happening with Covid.”

“We all experienced those seven weeks. We know what it’s like not to have a paper,” Tim Aughenbaugh told me. “You would hear that someone had died, and you didn’t know because you hadn’t seen the obituary. In this neck of the woods, there’s no television or radio station in town that covers our local news, and businesses were saying they had no way to get the word out about whether they were open, and what their safety rules were.”

“A newspaper is certainly about the present,” he said. “You open it up, and you learn what’s happening right now.” But Aughenbaugh–who before the pandemic had been involved with local journalism only as a reader and advertiser–said he had become increasingly aware that a newspaper was something more–that a journalistic presence helped a community shape itself, and connected its past to its future.

The past was most evident in highly popular “Fifty Years Ago” or “Days Gone By”-type features, recording high-school sports exploits, business openings and closings, other events that shaped the look and consciousness of the town. “But I began to realize that without a paper, not only is it harder to keep up with what’s going on now, but you can’t get a good handle on the future of your community, either” Aughenbaugh said. “A community needs a forum to tee up topics for discussion, get a sense of people’s views, debate ideas and discuss the path forward.”

“There was just a hunger for news,” Matt Kees told me. Kees had grown up in the area, moved away for education and technology work, then moved back with his wife, to raise their children here; he works remotely as a software product manager from his farm outside town.

I relay these observations knowing how ordinary they may sound. The power of hearing them in person, in this tiny community, was that they came from people most of whom previously had little or nothing to do with the journalism business, and suddenly felt its lack.

What they did: People in the national-security business often talk about a “whole of government” or “whole of nation” response to various threats. The people of this part of South Dakota–some multi-generation residents, some new arrivals from other parts of the country, some returnees after growing up there and moving away–launched what I think of as a “whole of community” or “whole of town” response to the disappearance of their newspapers.

Essentially, everyone pitched in, to do everything, about a business almost none of them was experienced in, and that all of them decided to take responsibility for. So far it has worked, or at least survived in viable-enough condition to deserve attention elsewhere. (For two South Dakota-based reports on the startup stage of the effort, see this, from Cory Alan Heidelberger of Dakota Free Press; and this, from Bart Pfankuch, in South Dakota News Watch. For a more recent look, see this, from Ariana Schumacher of KELO TV in Sioux Falls.)

One major decision was to combine two little publications into one county-wide journal. “That seems so simple and obvious now, but it was a big step at the time,” Matt Kees said. Small and adjoining as they were, separated only by seven miles, the two towns had longstanding rivalries and differences. Each would have preferred to keep its own publication. “The fact that they’d disappeared made this an easier decision,” Aughenbaugh said. As people in both towns worked on a new countywide effort, they also sought–and received–advice from Bill Ostendorf and Lynn Rognsvoog of Creative Circle Media, a consulting firm in Rhode Island whose mission is advising local publications on how to survive Covid and the larger economic plagues besetting them.

As for a business structure: the former owner and editor, Dale Blegen, sold the small newspaper building in each town to the respective local development corporations (which are nonprofit civic organizations). Then he threw in ownership of the papers themselves. The new paper’s operators took out loans totaling $20,000 from the development corporations–$15,000 from De Smet, $5,000 from Lake Preston–to get them through initial operating losses. But in fact the new paper has been cash-flow-positive from the start, so it never drew on those reserve funds and recently returned the entire $20,000.

The staffing structure of the paper is even more distinctive. It involved enlisting people from both communities, and other nearby settlements, in an effort to report, write, distribute, and sustain the paper. The clearest way to illustrate this might be with thumbnail bios of those who have joined in. The names and details might not mean much to people outside the region, but the range of activities and backgrounds should be suggestive:

- The mayor of De Smet, Gary Wolkow, drives a 100-mile round trip to a printing company in Madison, S.D., each Wednesday morning, to pick up the 1,600-plus copies of the paper and get them them to the post office, retail outlets, nursing homes, and other sites in four small cities. He is listed on the masthead simply as “distribution.”

- The paper’s editor, photographer, and full-time paid reporter, Mike Siefker, is a former volunteer fire fighter, paramedic, and registered nurse who moved to the area from Texas and has taught himself the one-man-band skills called upon at a small paper.

- Tim Aughenbaugh’s aunt, Rita Anderson, grew up in De Smet, worked for many years in Colorado, and returned as economic-development director for the De Smet Development Corporation. She writes regularly for the paper.

- Billi Aughenbaugh, who is married to Tim’s son, grew up in Lake Preston and worked on the high school paper there. She runs a social-media business and now is a contractor for the paper, responsible for, among other things, its “pagination” (final layout).

- Penny Warne, a retired English teacher from De Smet, is a volunteer copy editor. (She described why she decided to volunteer, in an interview with Mike Siefker, here.)

- James Jesser, a a special-ed teacher and greenhouse owner, has written news from his town of Iroquois, and is one of several regional contributors.

- Ann Lesch, whose family runs the Ingalls Homestead tourism business, volunteers for business administration and financial duties for the new paper.

- Matt Kees, in addition to his own software work and his role as president of the De Smet Development Corporation, writes about golf and youth baseball for the paper, and helps with its IT, all as a volunteer.

That’s only the beginning of the list. A woman who had been a sales director for a major national newspaper moved to the area, where she had family ties, and agreed to help the Journal. So did another woman, with long experience in print-and-digital ad sales in California, who had come to South Dakota during the pandemic. In all the paid staff numbers one full-time reporter and editor; two part-time workers; and a salesperson paid on commission. The rest are volunteers–as you see on the masthead below:

Years ago, on our first visit to the similar-sized city of Eastport, Maine, Deb Fallows wrote about the phenomenon of everyone, doing everything, to keep the community going. The newspaper editor was also the ticket-taker at community-theater productions. The barista also ran a clinic. Something similar is true of the Kingsbury Journal and its local, mainly volunteer staff.

Having spent virtually all my working life (so far!) in the reporting-and-editing business, I was touched by two of the discoveries that this volunteer army of civilian journalists had made. The first was how hard this process is. “I used to take it for granted that the paper would just appear in the mailbox,” Tim Aughenbaugh said. “Now I know it’s like a minor miracle to publish one — and as soon as you finish an issue on Wednesday morning, the next Wednesday is already coming at you.”

The other discovery that the new Kingsbury team of unexpected journalists shared, when we met a dozen of them at the newspaper’s office, is how satisfying and enjoyable (albeit exhausting) the whole process has been for them. People from every walk of life enjoy having a say, sharing what they’ve learned, becoming known in their town. This principle is familiar from sports-talk radio — “let’s hear from Joey, in Queens” — and from curated reader-mail features. (As opposed to the downward spiral of unmoderated comment sections.) The people of Kingsbury County have put the same impulse to work in creating a newspaper.

“People like to have a chance to have their voice,” Matt Kees said. “I think an important element in long-term success is including that community voice.”

Local residents have started columns on cooking, on wildlife, on sports, on history. “The volunteer nature of our model is actually a nice way to deal with complaints. We just say: Ok, we’d be happy for you to join us–why don’t you write about it?,” Aughenbaugh said.” Contributors and columnists have enjoyed developing a following, and hearing from their neighbors and people on the street.

Is this viable in the long term? That is more than anyone can now say. Tim Aughenbaugh told me that advertising for the new paper has returned to roughly the level of the two previous papers combined. What media people call “penetration”–how aware people are of your publication–must be phenomenal. Those 1,600+ weekly issues got to a county of only 5,000 people. Subscription rates are $65 per year in nearby counties, $75 elsewhere. The paper has an actively updated website.

What it means: Is the new Kingsbury Journal “the” model for restoring local journalism across the country? Obviously not. It is barely a year and a half into its new existence; that existence depends on community ties and efforts that might be harder to create elsewhere; its story might look different a year from now, or a decade. The volunteers we spoke with at the paper’s office said they thought the enterprise had moved from the initial all-nighter startup mode, to a sustainable cruising speed. But again, they’re 60 weeks in, and Wednesday keeps coming.

So this is not “the” model. But it is “a” model — like so many others we have discussed. With each example of success, people elsewhere can think: perhaps a version of this approach could work for us.

Perhaps nothing can solve the problems of local journalism. But perhaps everything will.