It might be the mural painters in Ajo, Arizona, or Charleston, West Virginia; or the public-art sculptors of Greenville, South Carolina, Rapid City, South Dakota, or Holland, Michigan; or the politically active artists, in San Bernardino, California, or Laramie, Wyoming. Sometimes they brought a sense of the town’s history or a fresh look at its culture. Sometimes they used their trade and artistic gift to make statements and move political action.

Most artists were working at the edge. They seemed somehow different from the rest of us who color inside the lines. That is part of why I wanted to return during the pandemic to artists I have met and known, to see how they are taking in this terrible new life and how they are responding through their craft and work. What were they saying and what were they doing?

I talked first by phone with Richelle Gribble, whom I had first met during her artist-in-residency in Eastport, Maine. Richelle is a serial artist-in-residence, having traveled for weeks or months at a time to places from the Arctic Circle to Wyoming to Berkeley. She is at home near LA now, working out of her kitchen. Her workspace, the counter and a pullout table next to it, competes with normal kitchen activities, and the result, Richelle described, is a mixture of paint tubes and tomatoes.

Richelle works on both big pieces and little pieces, which is convenient now. In Eastport, she had a two-room storefront studio, where she could lay out collections of local flora and fauna, and compose really big pieces. Townspeople strolling the sidewalks would regularly stop by the studio to see what she was up to, which was a feature of her residency. Now the only person who drops into her workspace is her partner, who, she says, spends his days on calls and zooms.

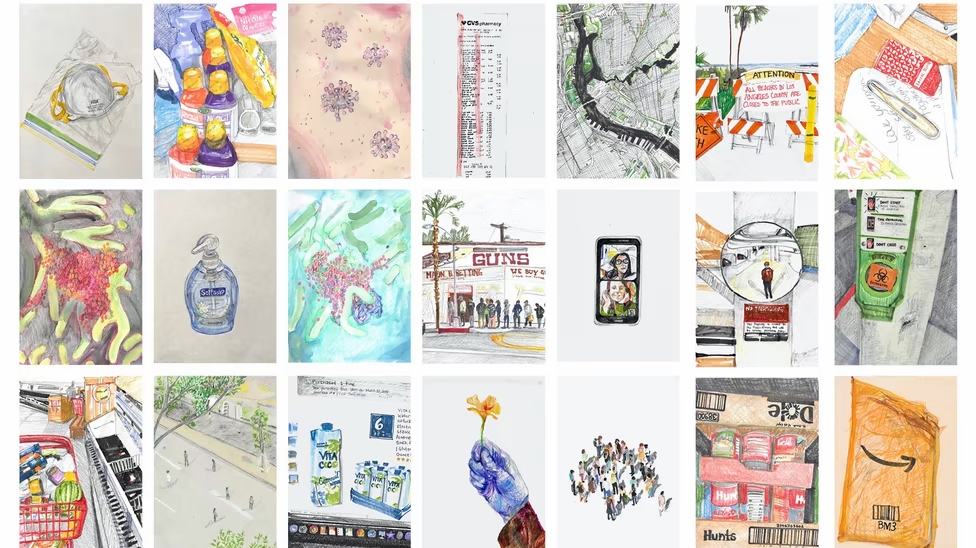

When I first met Richelle, her muse was everything around Eastport: the shoreline, the wildlife, and the nature around her. Now, she says, she is attuned to life closer in. In a project she calls Quarantine Life, she posts online a daily drawing of something she has just noticed, or experienced, or heard about, or felt. You’ll see shopping receipts, a discarded face mask on the sidewalk, sweet potatoes that are growing sprouts, a coronavirus rendering, and the well-organized, color-coded inside of her closet. Her goal is to track the days, she said, and her stack of drawings is growing taller and taller.

She is also participating in a global crowd-sourced project that includes not only artists, but others who are journalists, physicians, ecologists, songwriters, CEOs, astronauts, and more. It’s called Great Pause Project.

The plan is ambitious: Anyone in the world is invited to share written responses and photos on an online platform, to document and archive the pandemic experience. The hope is to learn lessons and gain insights that might otherwise be lost, and to create a tangible, collaborative record to craft the story of this time.

Richelle describes one of the crowd-sourced initiatives, the Window Effect, where people contribute photographs taken from their windows. The impressions evoke everything from weather checks to glimpses through prison bars to effective shields against the virus to daydreaming. And another, the COVID-19 Photo Diary is a photograph collection a bit farther beyond the glass windows, out into the neighborhoods.

Great Pause Project also includes a crowd-sourced written survey, called the echo-location survey, which will build a record about life during the pandemic: People answer questions about how they are feeling, how they have changed, what they notice about their environment, how they see the future, and what lessons they take from living this experience.

Richelle has long explored the idea of interconnectedness in the world through her art. She sees the pandemic era as a chance to have a broader reach by working very collaboratively with others. “If I share art just within my own circle” she says, “my art reaches a few people.” But if it becomes part of something bigger, she explains, “Others will say: Oh yeah, that’s what a global pause felt like or that’s what the COVID experience was.”

I talked with Barbara Liotta, who is an artist in Washington, DC and for the record, a longtime friend. For decades now, she and I have talked about everything: children, husbands, families, her art, my writing, travel, swimming, books, and lots other things. I’ve traipsed around rock quarries with her to source stones for her sculptures, watched her suspend a 57-foot net panel over the side of an 11-story building, and celebrated her openings. She has visited us on our faraway journeys, flown in our little plane, gone to my author events and had parties for them. We prop each other up. So naturally, I turned to Barbara to help me see her artist’s sense of life during this time.

Barbara has a studio behind her house; it used to be a garage, with a concrete floor and high enough ceiling to hang her work. At the beginning, she told me, the lockdown made her feel like a character in a 1940s British movie. We should “buck up and take care of each other and confront this thing by being good community members,” she said. While most of us were cleaning out attics or basements, she was sorting and arranging her enormous collection of formidable, heavy shards, chunks, and slabs. Serendipitously, she came across what she described as “beautiful, gold, sun-drenched granites” and she created a series of warm sun pieces to will in a different mood.

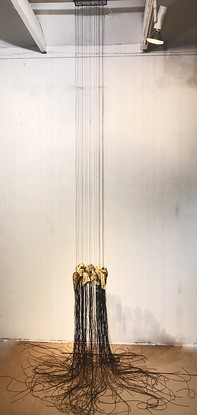

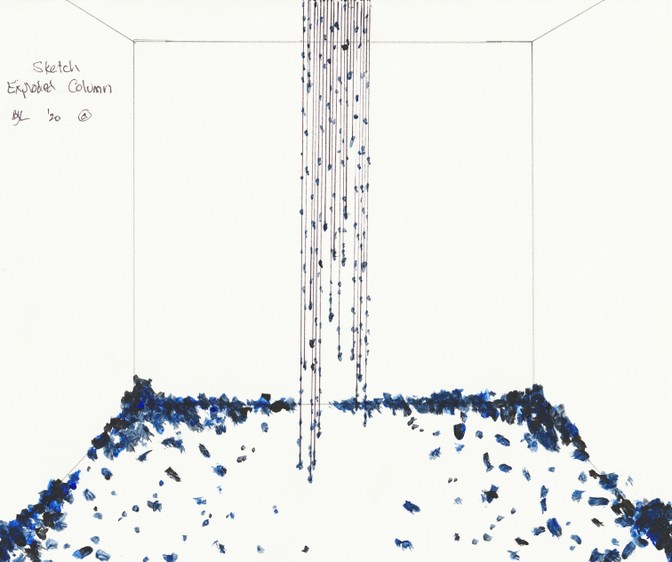

Weeks passed, and as the pandemic with its tragic and awful state came to dominate everything, her work reflected the change. She told me. “As an artist, I can’t not address it, but the immensity of the shift requires that I let it sink in and allow my vision to mature.” The result? “I’ve been drawing and proposing a very dark, dark piece of exploded columns and shattered rock.”

Like for the rest of us, who seek some lightness or humor anywhere these days, one bright moment came on a video call with her son, an emergency room doctor in San Diego, and his new wife, as she was directing them how to install a small hanging sculpture she had shipped them. “A little farther back, off to the right, now left a bit,” she narrated the smart-phone enabled installation process. I saw this as a simple, lighthearted moment. Barbara saw an interpretation: “Art means civilization means hope,” she wrote me, “like an equation.”

Like many other artists and many of the rest of us, her work has been sidelined from the public. An exhibit at the Gallery at MASS MoCA hangs inside for no one to see it. A symposium was cancelled. Future events are falling by the wayside. While many artists have shifted online—musicians, singers, actors, performing artists—Barbara says that option doesn’t work for her. Her art is three-dimensional, and being present helps experience it. “The trouble with my work now is that it needs a venue,” she concluded, with the pain of the sculptor’s version of If a tree falls in the forest …. “It is my work, but my work is not going anywhere. It doesn’t count if no one sees it.”

I also talked with Andrew Simonet, who cofounded and directed Headlong Dance Theater in Philadelphia for 20 years. He left that role seven years ago and pivoted to write young adult novels. He also founded an incubator called Artists U to help artists take practical steps to create a sustainable life as an artist. When I talked to him, Andrew was in Vermont, where he decamped from Philadelphia with his family.

We talked about the work ethic of artists and how it syncs with this moment of pandemic. He explained something I hadn’t thought about before, but it made perfect sense when I heard him say it. Artists, he said, are “very comfortable with uncertainty. We push away from what we know.” And this way of living and working, Andrew Simonet argued, should be encouraging to artists who may need encouragement right now for how to meet the pandemic and push on to make their art.

As artists, he declared, “This is what we train for.”