Along the way of our reporting for American Futures and Our Towns, I ran into the stories of some remarkable women—living and dead. Eliza Tibbets, who planted the first navel oranges in California; Isabella Greenway, who helped shape the entire copper-mining town of Ajo, Arizona, went on to found an airline company and the iconic Arizona Inn, and became the first woman representing Arizona in Congress; Jerrie Mock, a housewife from Columbus, Ohio, who chased the dream of Amelia Earhart to become the first woman pilot to circumnavigate the globe on her own; the Women of the Commons in Eastport, Maine, who are a big part of rewriting the civic, cultural, and commercial story of Eastport, Maine; and Tracy Taft, an educator and organizer who followed Isabella Greenway to Ajo, Arizona, to drive its change from a failing former-mining town to a thriving community based on the arts.

Recently, I hit the motherlode, where well over 200 women from rural America met in Greenville, South Carolina for a gathering of the Rural Assembly, a coalition of nationwide organizations that advocates for rural communities. This one was the first ever Rural Women’s Summit. (Okay, I counted on one hand the number of men who were there, too.) They met to talk about civic life, incarceration, health, water, education, poverty, faith, relationships, conservation, family, entrepreneurship, all in the context of women living in rural America. They framed their comments from their experiences as women in the military, as organizers of movements, as filmmakers, journalists, artists, nurses, lawyers, civic leaders, mothers, convicts, politicians, faith leaders, actors, and more.

“The diversity of voices and experiences in the room was meaningful and telling,” Whitney Kimball Coe, of the Center for Rural Strategies, told me after the conference, via email. “It pushed back on stereotypes of a monolithic rural America.”

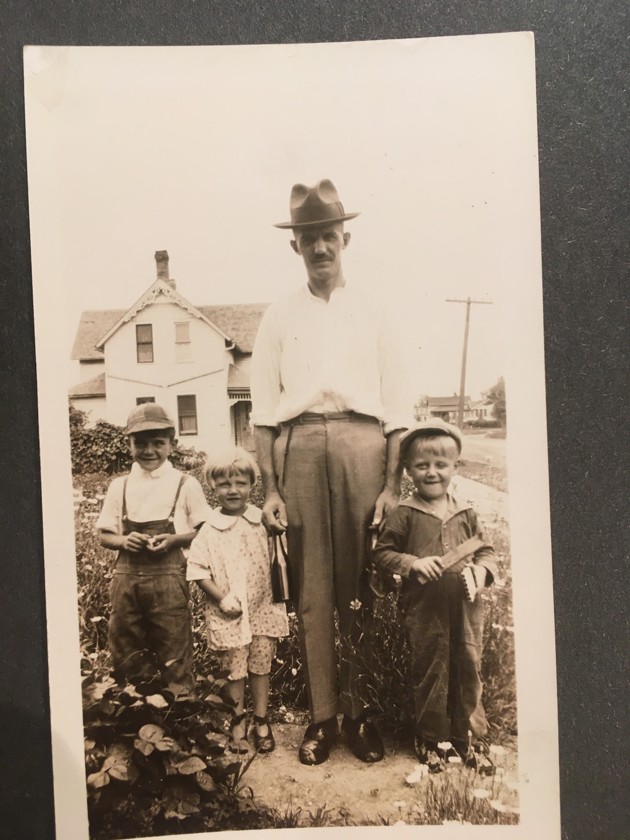

My own rural roots dwindled about a century ago, after my family had immigrated from Bohemia and Moravia, in the part of the Austro-Hungarian empire that later became Czechoslovakia, to the Midwest. Most of my relatives had lived in rural areas in Europe. My cousins and I of the American-born generation chanted that our forebears were butchers, bakers, and candy makers. My great-grandfather, who lived and died in the dozen-house village of Mlyny (mills in Czech) was the chief gardener for trees in Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s country estate, Konopiste.

I went to see his trees, maybe some had been saplings in his time, about 20 years ago, and then found my way to his village, where an older woman told me the story she heard growing up of the two young boys from Mlyny who went to America to seek a new life. One of those boys was my grandfather.

Mostly from photographs, I remember standing in the fields of tall corn in my great grandmother’s family farm in rural Minnesota. And as clear as it was yesterday, I remember the backyard garden in the West Side neighborhood of Chicago, where my grandparents ultimately moved, and where my grandfather (the baker) grew sunflowers that were twice my height. My rural connections are twice-removed compared with those of my friends from the small Ohio town where I grew up, who actually lived on farms. But I will defend some deep bloodline sense I feel when I see and listen to the stories of rural life in America today. Those are the feelings I took with me to the meeting of rural women.

I gleaned a few principles about the lives of rural women that I hadn’t appreciated before.

The first is how aggravations from a single issue can quickly cascade into a series of complications that make problems worsen toward intractable.

Let’s take water, for example. Martin County, Kentucky, in the coal country of Appalachia is, as one woman described it, a poster child for water crisis. We have all been enlightened by the stories of Flint, Michigan, which would not be public without the women on the front lines there, by the way. The broken infrastructure of water protection and handling in Martin County—cleanliness, safety, delivery, affordability, sewage—in Appalachian coal country is another piece of the troubled water story around the U.S.

This story of water there is intimate to the lived experience of the women who tell it and those who report it. By and large, it is the women who open the taps for water they use to cook, to do the laundry, to bathe the children, to drink. If the faucets deliver, which is not a given, the water often runs brown, sulfury, and smelly.

Reporting from those who live or spend time in Kentucky, be that in newsletters or rural press, adds a nuance of understanding that delivers insistent stories of a contaminated water supply, leaky and crumbling pipes, wastewater pipe shortages, industrial leaks and spills, a declining tax base from mine closures, rising water costs, and all the humanly compelling drama that ensues.

Then the cascade begins. The women bathe the babies, who then develop rashes. The women drive them long distances to see doctors, which is costly and time-consuming. Researching medical counsel or the alternatives of telemedicine often demand broadband connections, which are scarce, spotty, or thin in poor, rural America. Navigating coverage of telehealth from insurance companies is, as you’d imagine, complicated. And of course, all these steps require technology, transportation, and bill-paying, not to mention the wherewithal to accomplish them.

The problem of rural water into and out of rural homes is a speck in the universe of the bigger forcefield of water, which includes big agriculture, mining extractions, chemical runoffs, big industry, lobbyists, federal regulators, courts, big insurance. Crises like Flint’s notwithstanding, those of us who live in non-rural America usually take our water supplies for granted—or we at least trust that if something goes wrong, it will soon be fixed. But that is not necessarily the case in rural America.

It seemed clear that the case of bad water was not a one-off but rather an example of a pattern. I heard about other issues where one event cascaded into a flurry of others; violence on Indian reservations and the incarceration of women, especially mothers, were two of the worst.

The second thing I learned at this meeting of rural women is the particular way they address their problems and design solutions. It will not surprise you if I say that rural women approach solutions and take action with a driving practicality. Isn’t that how pioneer women and immigrant women and farming women survived?

It may surprise you (it did me) that the rural women wrapped this practicality with sentiments that you might link with being too soft, weak, or self-defeating (read: emotional, vulnerable, caring). And that they sought solutions in the places that you might consider unimportant or even a throwback to an earlier pre-feminist era (read: the kitchen, the living rooms).

But on the contrary, I heard women suggest that these “women’s ways” (my words), when they emerge comfortably and naturally, are powerful tools to make actions effective and arguments accessible to more people. The message I heard: Do not shy from showing vulnerability, caring, or emotion. Do not apologize for it. Use it. Go into the places that are your comfort zones for work that is uncomfortable and requires you to be brave.

Here are a few specific examples for taking action:

Run for office: VoteRunLead runs training programs and online tools to encourage women to run for office, and to help them win. A starting point is planting the idea, #runasyouare, for those who may think they’re not up to it and are reluctant to jump in. According to Erin Vilardi, VoteRunLead president, “There are over 1,000 women sitting in elected office through our program. We have rates over 50 percent for first-time candidates winning their races,” adding, “One in five of our alumni are from rural communities.”

Practice radical hospitality: People’s Suppers and communal dinners are opportunities for public discourse about fraught issues, like LGBTQ issues, addictions, and arrival of refugees. Sometimes, faith leaders or places of worship step in to bridge gaps. Jennifer Bailey, an ordained itinerant elder at the African Methodist Episcopal Church and director of the Faith Matters Network, said, “Women can turn a box of spaghetti into a feast.”

Create safe spaces: Basketball courts on church grounds, daycare centers, quilting clubs in living rooms, shelters, gardens, girls’ night out. Look for activities that build familiarity and trust, and are just nice as a vehicle for discussions, ideas, and actions.

Take healthy steps at the source: get rid of deep fryers in hospital cafeterias; provide applications to SNAP and other food programs at food pantries; change the menus in school cafeterias. These are easy wins.

Tell stories: Use different frames to tell the big stories, in local media or as freelancers or in entrepreneurial journalistic start-ups. These give (new) voice to issues. There were a number of examples of reporting at the source, like the Daily Yonder, High Country News, Southerly, and 100 Days in Appalachia.