Jim and I returned to Columbus, Mississippi, recently to see how development in the Golden Triangle was progressing, and to visit one of our favorite schools, The Mississippi School for Mathematics and Science. The MSMS is a two-year public residential school for students of all races, ethnic groups, and economic backgrounds from all over Mississippi. You see a glimpse of the school and some of its students at work in the science labs at the end of this Atlantic video produced this past fall.

Don’t be fooled by the name of the school, with its emphasis on math and science. The school is equally impressive in its humanities programs. We wrote about MSMS here and featured some of the essays from students last year here. We have more for you this year.

Emma Richardson teaches the creative writing class at MSMS, and the essays and poems here are all from her students. This is the first of two collections

As Jim and I have traveled the country over the last three years and have seen many, many schools, we have come to appreciate the deep dedication and generosity of some special teachers. They are pouring their minds, talents, and hearts into their work, and they are changing the fortunes of their students one life at a time. Hats off to Emma Richardson and to Thomas Easterling, the English teacher at MSMS who first found us and invited us to come to Columbus.

Agrippa Kellum is from Starkville, Mississippi, and graduated from MSMS last May. He now studies government, information science, and philosophy at Cornell.

Fish

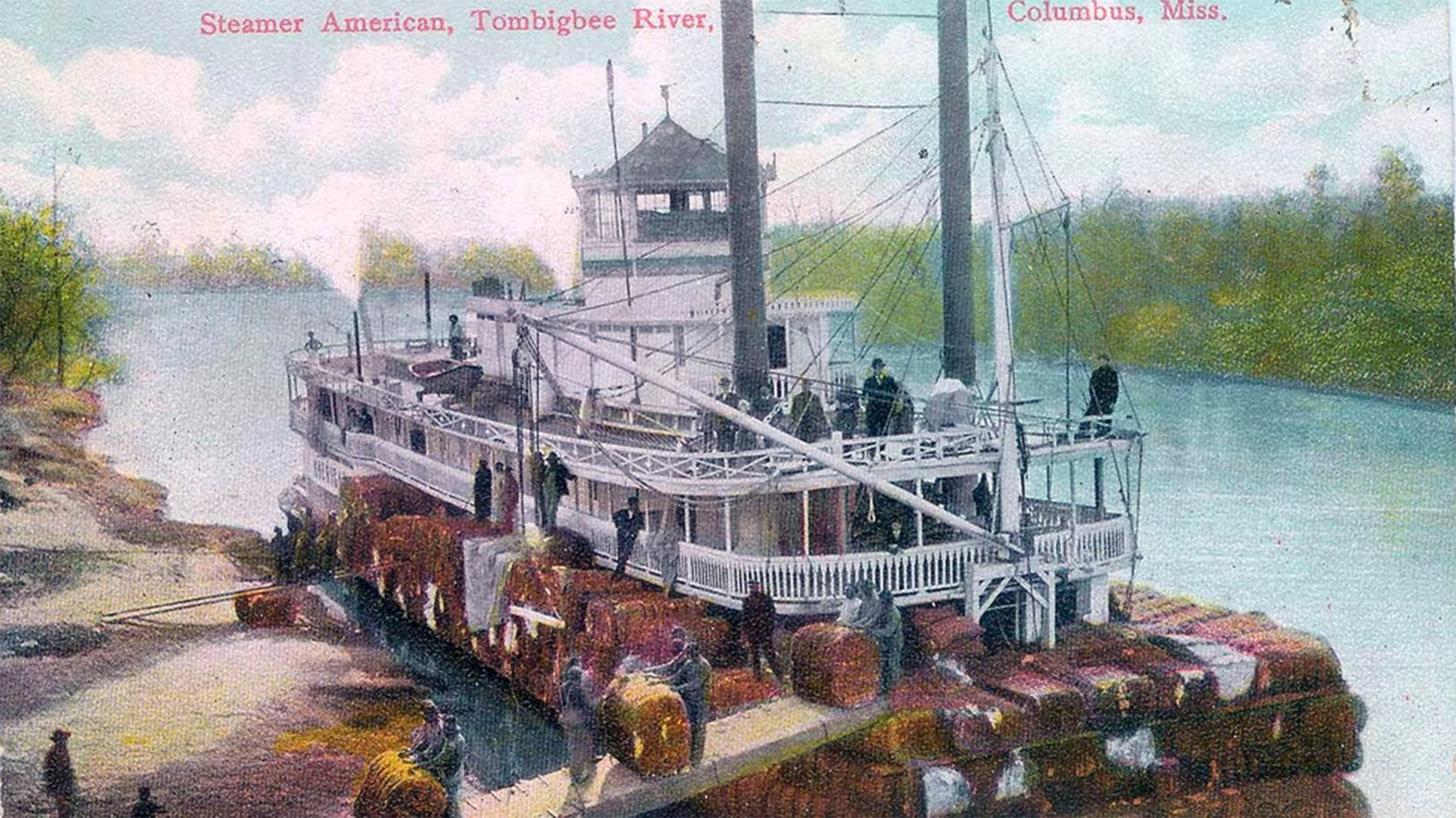

Fish in Mississippi must rely merely on touch and smell to navigate our muddy rivers. Twenty walking-minutes from my residential public school in Columbus, Mississippi, a platform floats on the Tombigbee River. On it, I sit about an inch or two above the water. At no point in my life have I ever lived more than a thirty minute drive from this waterway, and at no point in my life has it ever looked familiar to me. It’s solid brown and so opaque you could lose track of your own hand in this water. Life in Mississippi can be murky.

Life here can be murky because I can’t see out. I can’t see what the rest of the world is like. I’ve written emails to those who I think lead the kinds of lives I might want to live, to see what they have to say about life beyond the Tombigbee. But I can’t see any of it for myself. I can’t feel their surroundings like I feel mine.

What’s in Mississippi? Peering down on its surface, some see warm hospitality and hushpuppies. Some see homophobia and racism. Some see cracked roads and hungry mouths. I’ve spent seventeen years feeling my way through this state.

Let me tell you what I’ve found:

It’s easy to feel different down here. People like me, who aren’t Christian, often feel like outcasts. People like me, who really love reading–thinking–about Sartre and evolution and binary trees and real-life trees and everything but football, often feel like they have nobody to talk to. I’ve spent many lonely afternoons at my lesbian parents’ home to which many children were invited, but few permitted by their parents to come. Feeling alienated, it’s easy to curl up and wait for the current to carry me somewhere else.

I’ve also found that those feelings of alienation are a trap. My crossed arms in line for the Eucharist every Thursday at Catholic elementary school were met with nothing more nor less than a soft prayer and a smile. A gruff Christian man whose chicken coop is modeled after the Sistine Chapel taught me to love history. Southernness is not the antithesis of intellect nor kindness, and even though nobody can give me all the answers, everyone has something to teach.

Over the years, I’ve learned to seek out human connection through the murk. I’ve found it under gazebos and magnolia trees like under overturned rocks, with used-to-be strangers like Dudley who writes detective novelettes and Elizabeth who studies musical speech therapy. The world around me is brought to life as something to soak in rather than merely drift through. It can be scary to search for social sustenance–so necessary for growth–knowing I may be bitten or crushed, but without doing so I’d surely starve.

I’ve been at my residential school for a year now. I’ve learned a lot from being out on my own, farther down the Tombigbee. I remember watching this year’s new juniors on one of their first nights here. Many sang and socialized in a large circle. Others floated by on the outside, not quite ready to poke out of their shells. Remembering my own awkwardness giving way to close friendships ignited by brief nighttime walks, I encouraged them: “Try finding somebody to walk with. It might be uncomfortable, but it’s worthwhile.”

I don’t know what lies ahead, far away from the Tombigbee River. I find it easy to forget how big the world really is. I don’t know what the people I’ll meet will be like. I don’t know what opportunities or options I’ll have. I don’t know what I’ll see or who I’ll become. I’m not sure if life ever becomes less murky. If fish are bothered by the uncertainties of living in this opaque brown soup, they don’t show it. I’ll just keep feeling my way through.

Summar McGee is a senior from Edwards, Mississippi, which is not far from the proposed site of a new, billion-dollar Continental Tire factory.

Pickin’ Day

Plunk! Okra echoes in neon orange bucket—

Swarms of insects bombard my face and

I am drenched in sweat.

One by one, we strip each hardy stalk:It’s pickin’ day with Big Mama.

A well-oiled machine,

Her gnarled hands pick, pick in rhythmic motion:Grab.

Twist.

Pull.Grab.

Twist.

Pull.Big Mama hums off-tempo gospel between chews of tobacco.

Her slate-blue polyester dress hides mud-caked work boots.She trods forward with hefty hips swaying,

Moves with just the right amount of Southern sass.The weeds between the rows of okra tower over Big Mama.

Like clockwork, she hacks away with

Rusty pocket knife hidden in her bosom,

A deep and present feeling.The scorching heat of Mississippi sun sears my flesh.

My hands—red, swollen, callused

My skin—covered in bumps from furry okra leaves

I long for a break,

But I don’t stop.

’Cause when it’s all said and done,

The okra don’t pick itself.

Makayla Raby is a senior from Ecru, Mississippi, which is not far from the birthplace of Elvis Presley, Tupelo.

Trade

Daddy smiled

as he stuffed the

rusted trunk full

of green, frayed

suitcases and

plastic Walmart

sacks, double bagged.

He spit out

black sludge

onto the dry,

cracking dirt

and muttered,

“Don’t go city

on me, girly.”

He grabbed

my pale,

uncovered shoulders

and pulled me

tight against him.

His sweat soaked

my shirt and

I sniffed one

last gulp of him.

Pine, sweat, and beer.

He released me

and I hopped into

the decaying

Buick Century.

Momma slapped on

her sunglasses

and lit up her

cigarette, pulling

onto Highway 15.

I watched as the

trees were traded

for towers, the

flowers for cars,

and the animals

for people.

I took a leap

into a bottomless

unknown and I

traded my

down-home roots

for opportunities

not found amongst

the deer, the trees,

or the flowers.But I never went

city on him.