Arriving in Tucson, we felt the inklings of coming full circle with our American Futures project. Only one more leg of our journey, about 400 miles, before we reached our destination of the San Bernardino airport, and on to a writing base at the University of Redlands in Southern California. For the record, here, here, and here are the three previous road reports since we departed from Washington D.C.

I was very excited about finally getting to Tucson. During our several visits to Ajo, Arizona, about 130 miles to the west of Tucson, I first learned about one of the fearless, indomitable and I daresay under-appreciated women who left a mark on America. Isabella Greenway was Arizona’s first Congresswoman, as part of FDR’s New Deal Democratic majority. But before that she helped build and bring the beautiful copper-mining town of Ajo, Arizona to its heyday. We visited Ajo several times over the past three years, and have chronicled some of its creative rebirth.

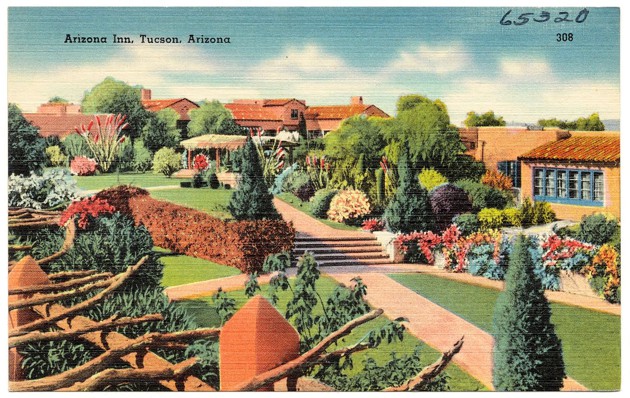

In 1930, after her time in Ajo and before her time in Congress, Isabella Greenway also founded and opened the Arizona Inn in Tucson, which was, I had heard, still thriving today under the family eye.

Over our three years of landing in the towns of America, we could never be too choosy about hotels. We considered ourselves lucky if we found a place with “suites” in the name, as in “Homewood Suites” or “Best Western Suites” or “Hampton Inn & Suites.” This was mostly because “suites” suggested an on-site place to do laundry and a little extra elbow room, which were both welcome attributes when two people were working in the same space and also generating a lot of dirty clothes.

So, a visit to the Arizona Inn was very special, and it turned out to be exactly what I imagined. Isabella Greenway herself described it as “a simple, home-like, cottage hotel” but it is much more than that, with high-ceilinged-oversized rooms, quiet green spaces, a big pool (almost 20 meters by my stroke count), wonderful food, and a hospitality still imbued with the family’s sensibility.

On a whim, I emailed the current proprietor, Patty Doar, who is the granddaughter of Isabella Greenway. To my surprise, she emailed right back. We met the next morning with her and her son and co-proprietor, the writer Will Conroy, swapping stories and photos about the different pieces of the story that we each knew.

We all had stories: Our updates on Ajo; their recollections of Isabella Greenway; connecting the dots between Ajo and Eastport Maine, where we also spent several American Futures visits; Isabella’s lifelong friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt; and her visit to the Roosevelt’s summer camp at Campobello Island, right across the water from Eastport. Such serendipity was a special feature of American Futures that we had come to relish and appreciate.

We left Tucson reluctantly, but with the auspicious sign of strong tailwinds, the first we’d enjoy on this cross-continent trip. Just north of Gila Bend, Jim and I were chatting about our introduction to the area’s Barry Goldwater Bombing Range back when we were first visiting Ajo (as described here), and the impressive aerial training of the Air Force A-10 attack planes and other military aircraft in the vicinity.

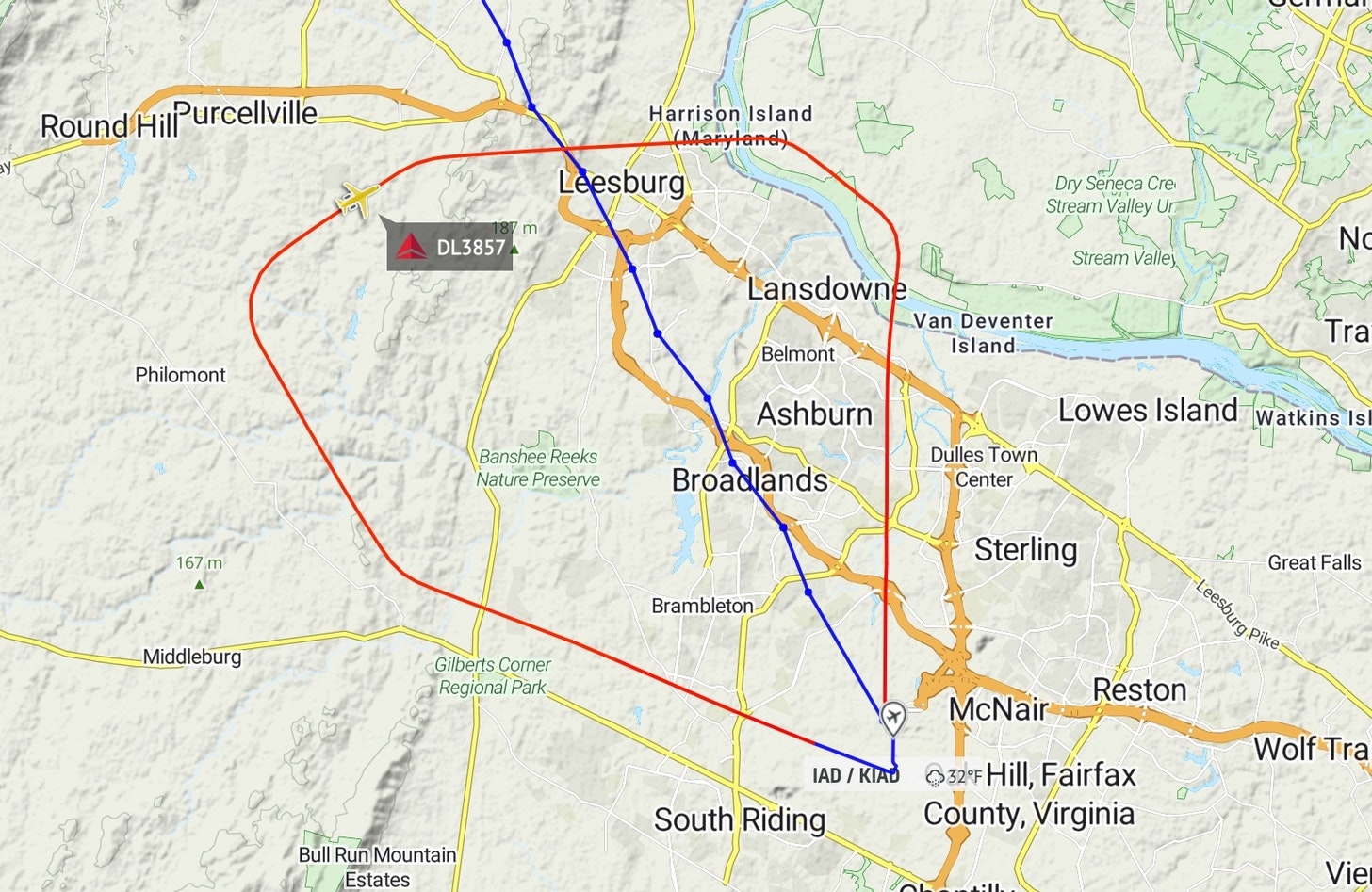

About then, the air traffic controller (ATC) told us they had lost radar contact with our plane. This wasn’t so surprising—it often happened with a relatively low altitude flight, or in remote areas far from controllers, or with natural impediments like mountains. Jim recycled the transponder, which often cleared up the connection between our plane and the controllers. This time, nothing.

Then the dials and gauges on the cockpit monitors—showing ground speed, wind direction and speed, location, just about everything—began to go haywire. They spun around randomly, showing a 150 knot headwind, then a tailwind, then no wind. The moving map showing our location, waypoints, position relative to obstacles and restricted airspace and other airplanes, suddenly blanked out as if it had no idea where our plane actually was. Red warning signs popped up on the dual GPS guidance systems (almost everything in the plane’s critical instrumentation has a backup) saying that they had lost their signal—the sort of thing you see in a car if you’re in a long tunnel.

I could tell that this was getting Jim’s attention. Then we both were alarmed by an urgent automated voice yelling “TERRAIN! TERRAIN!” This was from the system designed to give a last-minute warning if the plane was headed to dangerously high terrain (like a mountain, or anything with a higher elevation than the plane’s). We were getting this warning even though the closest mountains were dozens of miles away, and the desert floor was in clear view many thousands of feet below us. Jim switched to his old-school, pre-GPS “VOR”-based navigation systems to figure out where we were supposed to go, and how we could keep clear of the abundant nearby military-restricted zones. (It was easy enough to keep clear of the mountains, just by using our eyes.) Once Jim determined that we had lost all GPS guidance, he felt safe disabling the incessant TERRAIN! TERRAIN! warning, which was triggered because the plane’s instruments had no idea where the plane was and were being hyper-cautious because of surrounding mountains. I studied the dials, thinking— overdramatically—that this is how the world as we know it would look during some kind of nefarious global technological takeover.

It was dark comfort to hear a call from United 404, reporting to ATC that their GPS had also just conked out. At least it wasn’t just our plane. But, hey, what did it mean that others planes’ GPS were going out? And, an airliner’s?

The ATC said calmly, there must be GPS jamming going on, as part of a military test exercise. As we crossed the border into California, after about half an hour of no GPS, the guidance signal flickered back on. Later, on the ground, Jim learned that the Air Force was running a month-long trial in that area, testing the effects of intentional GPS outages. Thanks for letting us know, I thought.

As we flew over Palm Springs, the aerial roadsigns were becoming familiar: the mountains, the towns below, the windfarms, the Banning Pass that would let us through to the Southern California basin.

We opted for the route straight through the pass, although a controller told us about a pilot report from half an hour earlier of moderate to severe turbulence. In windy conditions, the Banning Pass can be dicey, because it’s the very narrow outlet through which air from the Mojave Desert to the east spills into the Los Angeles basin. Bumps are never fun, but they’re not actually dangerous to the plane, and the pass was by far the most direct way to our destination in San Bernardino. We tightened our seat belts, put away all loose items, and got ready for the dozen or so miles of potentially rough air between Palm Springs and the pass’s outlet near the city of Banning.

As it happened, we needn’t have worried. The turbulence didn’t materialize; the air was smooth. We spotted the San Bernardino Airport (SBD), and Jim set up the route for landing to the east. The pilot in front of us reported a “go around,” or missed landing, because the crosswinds were so gusty as he neared touchdown. He said he would circle around for a second try. Jim guided our Cirrus in, hovering near touchdown in the gusts for a few hundred feet and remarking to the controller that he was happy for the very long and wide runway at SBD, which had once accommodated B-52s when this site was the now-closed Norton Air Force Base.

Arrived. And feeling a world away from Washington D.C., some 3000 miles and four days later.