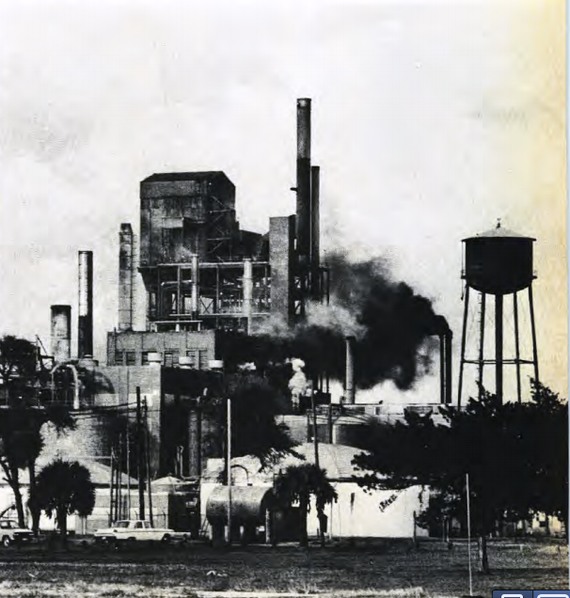

The picture at the top of this post shows the ruins of the Gilman Paper Company, in the coastal Camden County town of St. Marys. “Ruins” is the only possible term. Back in the early 1970s, when a young Jimmy Carter was running for governor of Georgia, Gilman was a fearsome political force in the state and essentially the only employer for many miles around. “Gilman Paper Company is the only major Georgia industry south of Brunswick and east of Waycross,” its manager said in a speech around that time. “It can safely be stated that not less than 75 percent of the economy of Camden County is directly dependent on Gilman Paper Company.” The picture below, from a Harper’s article about St. Marys in 1972, is the same site as in the shot above, when the mill was running full-tilt and employing most of the working-age people in town.

Back at that same time, when I was just out of college and my soon-to-be wife had a year still to go, we were — along with my sister and half a dozen other contemporaries — part of a Ralph Nader team dispatched to write about pollution, tax evasion, economic peonage, and other aspects of company-town life in now-hyper-stylish Savannah and other paper-mill towns in Georgia. The result was this book.

St. Marys was the most bleakly Dickensian of the places we visited. The mill paid good wages, in exchange for all-encompassing political and social control. Its corporate attorney was also the State Representative, and was the county attorney too; the result in tax policy and environmental regulation was predictable. The mill’s manager was the local Big Man. The company’s owners — the Gilman brothers of Manhattan — lived an art-patron life far removed from the harshness of their family’s company town. In the past few years, whenever I have gone to brutal, polluted, boss-run factory towns in remote China, I have thought back to St. Marys. It wasn’t that long ago that China’s current reality was tolerated in the U.S.

What happened next is too convoluted to attempt to explain here. In brief: a young millwright named Wyman Westberry, who had become disgusted by what we’d now consider China-scale despoliation of the local river and marshlands, drew press attention to what was happening in this little enclave. That’s him at left, around the time we first met. He called me late one night, we went down to learn about his town, and we wrote about him in our report. Eventually 60 Minutes and national and statewide media got interested in St Marys. In the midst of the furor, the local Big Men put out a contract to have Westberry killed (the going rate was $50,000, but the would-be hit man decided to keep the money but not carry out the hit). The administration of new Governor Jimmy Carter began paying attention; and — at the end of an Elmore Leonard-worthy tale — Wyman Westberry ended up surviving, and much of the local establishment either ended up in prison or died before coming to trial.

You can read the subsequent blow-by-blow — and I actually hope you will — in a Washington Monthly article I wrote ten years after all the drama*, or in a (subscribers-only) Harper’s article by Harrison Wellford and Peter Schuck from 1972, or this more recent Forbes piece on the “Fall of the House of Gilman,” or from our original The Water Lords book. [*UPDATE The scanned PDF of this issue of the Washington Monthly, by Unz.org, is a little squirrelly in its layout. But when you come to what seems to be the end, on page 19, you can click the > button at the top of the page and it will take you to the rest of the story. Or, you can click on the Entire Issue button, which should do the trick too. I am biased, but I think it’s a gripping tale. For a while it had a movie option, which is something can’t say about a lot of things I’ve written.]

As I’ll describe in future dispatches, Wyman Westberry has stayed in town, and become a formidable figure — and in a very different role from mill wright at a paper mill. That’s him, on the left, a few weeks ago with me near St. Marys in the Okefenokee Swamp.

The city too is transformed. When we first visited, the pollution from the paper mill was so thick and caustic that, as in a scene from modern China, even the Spanish moss had been poisoned from the trees. Now the trees look like this.

Back then, there was a perpetual layer of ash on cars and houses downwind of the mill. Now the historic part of St. Marys — the part not subject to strip-mall sprawl near the Interstate and the Kings Bay naval base — looks like this:

And, downtown:

And across what had once been a fouled and polluted marsh:

All of this is set-up to the story we have looked at during our recent trip to St. Marys. What happens when the company at the heart of a Company Town shuts down? How different is the new “company town” life that has come with the area’s dependance on a large Navy base? What does the resilience of a man like Wyman Westberry tell us more generally? And is there any chance that a place like this, with its impressive high school and its ambition to become America’s next space port, can become a “talent magnet” like Greenville or Burlington?

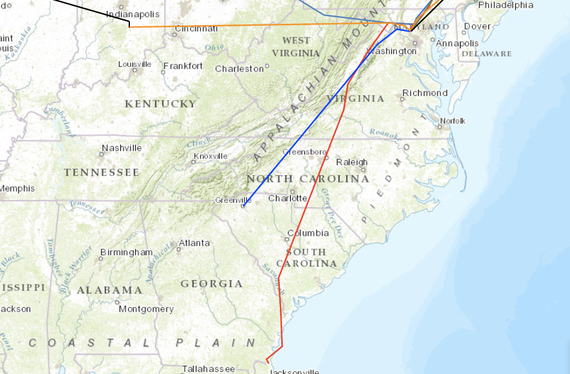

More in upcoming installments. Here is the route to St. Marys, in red — with the last little jog to avoid a prohibited zone over the Navy base.

And what the scenery on the way down looked like.

More of the St. Marys saga, starting with the “spaceport,” to come.