The small town of St. Marys, Georgia, differs from the other places we have visited in the basic structure of its economy. When we first went there in the 1970s, it was still what it had been for many decades: a company town, in the good and (mostly) bad senses of that term. Now it is a variant of the same thing, and that is the circumstance the city and county officials are trying to change.

The good of the old company-town arrangement was that the giant mill of the Gilman Paper Company provided paychecks for the overwhelming majority of families in the area. Indeed, the air and water pollution was so heavy, and the location was so remote, that a job with Gilman was the most obvious reason anyone would choose to live there. And not to belabor the bad — if you want belaboring, check out this previous post — but in addition to the normal distortions of a town all-dependent on one company and the people who ran it, the company badly abused its power in environmental and political ways, including hiring a hit man in a failed attempt to eliminate a local critic — that critic being a man who became our friend, Wyman Westberry.

That was then. Largely through mismanagement and the side effects of family squabbles, Gilman went through a long decline. You can read some of the details in this Forbes account, but overall it was a depressing personal and business saga. (Some other, better run plants still operate in the vicinity — you can just glimpse them in the distance in this shot below, from the former Gilman property across the wetlands toward the coast.) Gilman had been the largest privately owned paper mill in America, but 15 years ago the family sold it to a Mexican firm, and not long afterwards that firm closed the mill, eliminating some 900 jobs.

In 2007, the remains of the mill were blown up, despite some local efforts to retain and reuse them as startup sites, light-industrial buildings, or even monuments. That left what is now a rubble-filled “brownfield” between the city’s historic downtown and the coastal marsh. Here is a video of the demolition (in the last few minutes of the clip), with others here and here.

The good news for St. Marys and surrounding Camden County was that another mammoth employer had arrived even before Gilman went down. That was the US Navy. During the administration of the former submarine officer and former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter, and with Georgia Senators Sam Nunn and Herman Talmadge then big powers on Capitol Hill, the U.S. Navy decided that Kings Bay, immediately north of St. Marys, would be the East Coast home of America’s nuclear-submarine fleet. (The West Coast home is near Seattle.)

That big news of January, 1978, is memorialized in a front page shown in the local Submarine Museum (at right). Everything about the city was changed by the Navy’s arrival. In Gilman’s heyday, its manager had claimed that 75 percent of the people in the county owed their living directly to the mill. A few weeks ago in St. Marys, local officials told us that perhaps 70 percent of the regional economy was now related to the base — a figure that includes rental housing, retail, construction, and the other spillover effects of growth itself.

Gilman Paper Company, the previous gorilla, had been “local” but not in a good way. The local managers behaved as mini-tyrants (if you don’t believe me, believe the state and federal prosecutors who went after them), and the owners lived in New York City and seemed to view the mill mostly as a hinterland source of wealth. Their ongoing source of local investment was a resort plantation where artists and ballet figures, notably including Baryshnikov, vacationed and trained.

The U.S. Navy, the current gorilla, is by all accounts faultlessly well-behaved and good-citizen-like in its local relations. The submarine officers and seamen are an elite within the military — older, better educated, and more carefully selected than the norm, and not any source of trouble in town. But by definition a military presence is transient — and while some Navy officials come back to the area after retirement, the Navy represents an economic power that is in but not of the town. Much of the growth it has induced as been “just” growth — malls, restaurants, fast food, etc on the fringes of town. (This ingenious “swipe map,” by our John Tierney and David Asbury of Esri, lets you compare the 1990 and 2010 land-use patterns, given a sense of the strip-mall development around the Navy base and an I-95 exist.)

We were struck by how different this single-source dependance was from other places we have seen. Sioux Falls has a big financial-services industry — but also is a major retail and medical center, and has universities, and has growing high-tech sector, to say nothing of its huge agricultural businesses. Greenville used to be textile-dependent but now has automotive and other manufacturers, plus finance and services, plus a vibrant downtown, plus tourism and universities etc. Eastport is scrambling to create more of everything but is not reliant on any one thing. With variations, the resilience-through-diversification saga is also true of Redlands, Burlington, Holland, Rapid City, Winters (about which more soon), and other places we have seen.

The officials we met from St. Marys and Camden County are perfectly well aware of the imbalanced nature of the local economy. One school official described it, during the Gilman era, as the “Uncle Bubba” phenomenon. “If a kid was slacking off in school, you couldn’t tell him to try harder, because he’d just say, ‘My uncle Bubba will get me a job at the mill.'” Uncle Bubba can’t get people into the Navy, but another person said: “Most places talked about economic development, but we really didn’t need to worry about that. Around the time Kings Bay leveled off, the housing industry started to grow. We kind of thought, well, we don’t need traditional economic development. We kind of got our eyes off the ball.” But now, he said, “We have looked in the mirror and, for the first time in my life, found the political will to pull together.”

– Environmental plusses in the narrow sense: It’s a pretty downtown, which resembles better-known and more popular resort cities but with dramatically lower real estate costs. Tourists now troop into St. Marys for holiday celebrations (or sail in, along the Intracoastal Waterway), and to take the ferry over to the Cumberland Island National Seashore, historically a resort for the Carnegie family. So plans are underway to add to attractions, hotels, and other local life that would entice people to stay for a day or two rather than just pass through.

– Environmental plusses in the broader sense. The Fish and Wildlife Service map at the top of this item gives a hint of what is true for strikingly large stretches of the Georgia coast. Of the entire Atlantic seaboard, it’s one of the best-preserved and most beautiful parts, in addition to having great ecological significance for its wetlands. Beautiful places, especially by the coast, are increasingly where people with a choice of where to live, want to live. You can rebuild infrastructure but you can’t manufacture an ocean view. (Well, I’ve seen attempts in China, but you know what I mean.)

— Filling an educational hole. Camden County has a very impressive “career technical” high school, as noted before. It does not have any well-established post-secondary system. So a push is on to use public land to build a tech-related college, in hopes that this will be the next step in creating the educational / cultural environment in which new businesses might start, and toward which talented young people might be drawn.

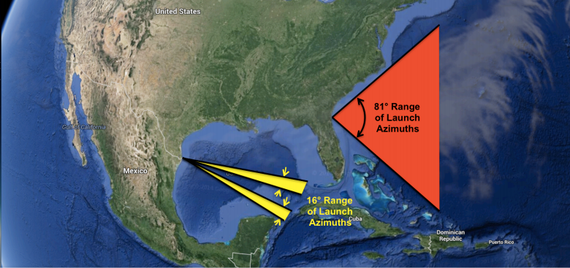

— And looking toward space. The commercial space-launch business is growing. According to local officials, this part of Georgia was in the running when Cape Canaveral was chosen as NASA’s main site in the mid-20th century. And so they are making a 21st-century push to build a new “spaceport” in a former industrial area (and one-time Thiokol rocket-test site) just north of town, where companies like SpaceX would be able to launch their vehicles.

The first fundamental truth of rocketry is that the closer a launch site is to the equator, the greater the free boost it gets from the Earth’s rotational speed. A related truth is that it’s better to launch rockets over the ocean than over populated land. Camden County has just now received a report from a Georgia Tech team headed by professor Robert Braun, a NASA veteran, on the advantages this means for its location. For instance:

Launches from Camden County have the capability to fly due east, maximizing the velocity boost from the rotation of the Earth and enabling more payload to reach orbit. The Camden County’s southerly location provides launch vehicles with an extra boost from the rotation of the Earth when reaching orbit. The Camden County latitude provides a 8% velocity advantage due to the Earth’s rotation relative to the Wallops Flight Facility [in Virginia] and a 4% advantage relative to Vandenberg Air Force Base [in California].

One of the most-touted recent spaceport possibilities is near Brownsville in southernmost Texas. Thus this compare-and-contrast chart from the Georgia Tech paper:

This is certainly enough for now. I’ll have a little more to say about the marshlands, and the space plans, and the local leadership later on. For the moment, here is how this fits into what we’ve seen elsewhere across America: even in a place that for now enjoys the benefits of a dominant, not-about-to-leave-town local employer, people clearly see the need to invent a new future for themselves, and are trying everything they can.