Second is to set up the next subject of our American Futures reports, which is the big, sprawling, now-troubled metropolis of San Bernardino, in the Inland Empire of Southern California, my original homeland.

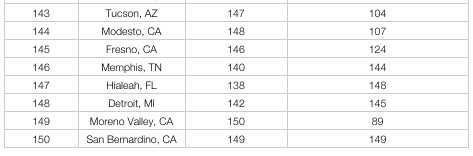

As I mentioned last month, San Bernardino has endured a combination of blows that actually make it a purer symbol of the post-2008 collapse than Rustbelt sites like Gary or Detroit. Its population was relatively poor to begin with; the main components of its blue-collar job base—a big railroad yard, a steel mill, an Air Force base—were each shattered within a few years’ span; its real-estate values shot up suddenly during the sub-prime bubble of the mid-2000s and then fell extra hard, making it one of the foreclosure centers of the country. Its unemployment rate neared 20 percent at the worst and is still twice the national level. San Bernardino is one of the poorest cities of its size (200,000+) in the entire country, and with Detroit and Stockton it is one of the three largest cities to declare municipal bankruptcy. A WalletHub ranking this week put it dead last on a ranking of job prospects in 150 metro areas.

The challenges, and the responses of people in San Bernardino who are trying very hard to make the best of the city’s circumstances, are for the next round of dispatches. For the moment, let’s make a connection to the theme of the City Makers conference. To wit, the functionality of American government at the national, state, and local levels:

Eighty-plus years ago, Justice Louis Brandeis popularized the idea that state governments could be America’s “laboratories of democracy.” Fifty-plus years ago, presidential candidate John Kennedy said that the federal government could “get the country moving again,” and then Lyndon Johnson used national-level tools to shift realities on voting right and anti-poverty efforts. Richard Nixon, whatever else he did, was by modern standards a radically “green” president, overseeing creation of the Environmental Protection Act, signing and welcoming the Clean Air Act, etc.

Now, thanks largely to paralysis at the national level, the laboratories of democracy and the arenas of practical-minded politics are generally the cities. “Cities, in short, are ascendant,” Mayor Reed of Atlanta, whom I’ll interview tomorrow, wrote last year. “People and businesses will turn to cities for leadership, bold thinking, effective services and, yes, hope.”

This is a point that Deb Fallows, John Tierney, and I have made repeatedly through the past year—to give one example, in this article about the surprisingly similar traits that otherwise contrasting cities share. High on the list of positive traits are collaboration, compromise, practical-mindedness, and a willingness to think of the whole community’s long-term good.

Because those traits are so central to so many cities’ success, environments where they’re missing or imperiled have all the greater handicap. That has been a major part of the San Bernardino story, as we’ll describe.

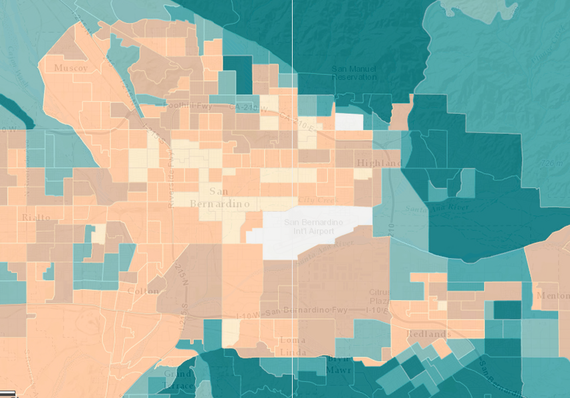

Preview: In one of the poorest cities in the state, salaries—and, more important, pensions—for the police and fire squads are, because of a highly unusual local rule, automatically tied to salary and pension levels in other, richer California cities. When Pasadena, Irvine, or Huntington Beach—all part of California’s prosperous coast, with household income, taxable base, and living expenses much, much higher than in San Bernardino—raise pay for their police or fire units, pay automatically goes up in San Bernardino as well. Thus a city with household income far below the national and state average thus struggles to pay police and firemen as if they were working someplace posh. In his final “State of the City” speech in 2013, longtime judge and former mayor Patrick Morris pointed out that “our working class families, where the average family of four lives on less than $40,000 [versus more than $50,000 nationwide],” were being served by firemen whose “average annual salary with overtime is $147,000.” Here is an interactive Esri map of the Inland Empire that lets you see median household income. Light brown means poor. (You can scroll and zoom to other areas too.) [Update: Arrgh, something was wrong with the layers in that map. Here is a screen shot to give roughly the same idea. San Bernardino is the lightest/”poorest” colored central tract. The large whitish area near the lower center doesn’t count, since it’s the very large San Bernardino Airport.]

Last fall some people in San Bernardino pushed a ballot measure to change this provision, and set salaries by collective bargaining as they are elsewhere in the state. The police and fire unions (whose members are not required to live in the city, and generally don’t) fought back hard to block the measure, and won. So San Bernardino continues its search for sources of future jobs while dealing with the here-and-now of civic bankruptcy, and the opposite of the “in this together” view.

Which leads me to, third, a source of information and hope about places where the various elements of a community are working together, rather than fighting to preserve their piece of the pie.

Through the past year-plus, we’ve been impressed by how many institutions are studying, promoting, and linking-together place-making and city-development efforts across the country. To give some of the most obvious examples: the Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings, directed by Bruce Katz; the Rework America project at Markle (of which I’ve been an informal part); ArtPlace America, with executive director Jamie Bennett; and many more, crowned of course by the Atlantic family’s own CityLab.

One you might not be aware of is a small undertaking in New York called The Intersector Project, whose goal is to publicize, connect, support, and promote public-private efforts like those we’ve seen in the healthiest, most successfully growing cities. Its name refers to the sectors that it (correctly) says must be connected for civic health: business, government, and NGOs (including universities, churches, libraries, foundations, etc). It offers case studies of where intersector cooperation has worked best, and a toolkit of how communities that need this kind of cooperation might develop it.

I first learned about The Intersector because it was created by a longtime friend, a lawyer, investor, and former government official named Frank Weil. I’m mentioning it here, and will say more in installments to come, because its emphasis so closely matches what we’ve seen in so many cities—and hope to see in places like San Bernardino.

Many problems of this American era mirror those of the first Gilded Age, a century ago. We know about the movements, reforms, and legal and cultural changes that redressed some of those problems the first time around. And we know their names—Populism, Progressivism, the muckrakers, the early women’s movement and environmental movements and efforts for African-American rights. Similar positive developments are afoot in the country now. It’s worth connecting and highlighting them, as The Intersector and other groups are, and figuring out and making known their new names.