Riverside, California is betting on its downtown pedestrian mall, contrary to the contrarian bet of Fresno, which is reopening its pedestrian street to cars, as Jim Fallows has reported here. (And for background on Riverside and the nearby similar-but-very different city of San Bernardino, see Jim’s previous post here.)

Fresno closed its downtown Fulton Street to traffic in the early 1960s. Riverside was part of that same early wave in creating pedestrian-only commercial street back in 1966. In 2008 the city doubled down, investing another $10 million to renovate and upgrade with landscaping, lighting and to add outdoor benches. We’ll have more to say about the rationale behind the second re-investment soon.

Jim and I walked Riverside’s pedestrian Main Street mall early on a lovely March morning with the city’s dynamic Mayor and multi-generation native son, Rusty Bailey. We started with coffee at the top of the walking street, choosing an outdoor table where the popular mayor would be a little less likely to be spotted by patrons inside. Then we strolled with him down the length of the street to City Hall.

Well, we didn’t stroll exactly. Bailey was pushing his bike, which he routinely rides to work, at a brisk pace, and I got the idea that “stroll” is not a word readily associated with Bailey. For context: he’s a local boy whose forebears were among the region’s original farmers and ranchers. He went off to West Point, served as an Army helicopter pilot and platoon leader, and then came back home to Riverside, where he worked as a public high-school teacher. He’s also clearly in the category of “happy mayors” we have seen around the country: people who feel as if having influence in and responsibility for a community they care for is about the best job now available in American politics.

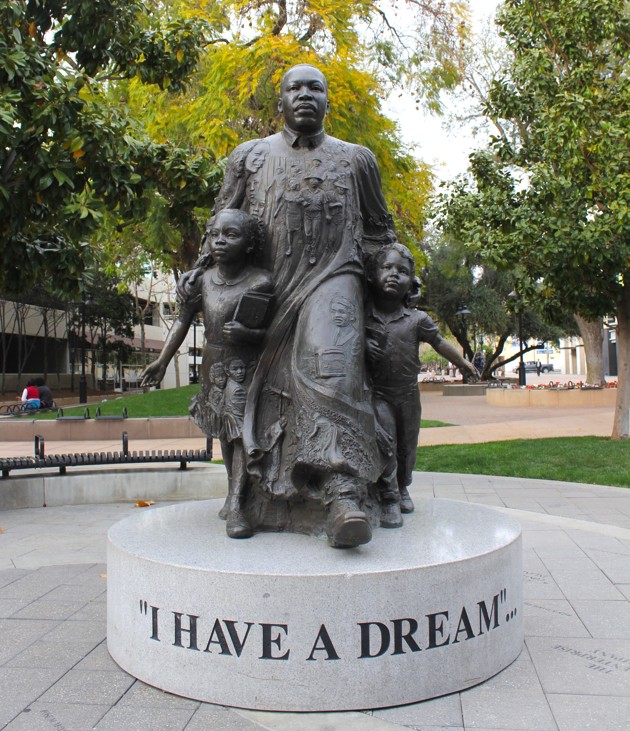

What really caught my eye was the series of six larger-than-life-sized monumental bronze statues, anchors of the so-called Peace Walk, from the Mission Inn to City Hall.

The three others need a little explanation for outsiders. One is Ysmael Villegas, a Mexican-American native of Riverside who won the Medal of Honor for his valor at the Battle of Luzon in WW II. Another is Ahn Chang-Ho, an activist for Korean independence from Imperial Japan, who founded the first permanent Korean-American settlement in Riverside in the early 20th century. On the day we visited, someone had decorated his statue with an elegant black-and-white scarf.

And then there is Eliza Tibbets.

Eliza Tibbets? I wondered, naturally, what she had done to earn herself a statue along this “social justice walkway” as then-mayor of Riverside Ronald Loveridge, declared it at the unveiling of the Chavez statue in 2013.

Eliza Tibbets’s statue, as you see her rendered in the opening image of the sculpture by artist Guy Angelo Wilson, depicts a beautiful, young woman with a remarkably pinched waist and arms raised in hope and an uplifting posture. The loveliness of the statue is all the more striking when you compare it with any photo of Eliza Tibbets taken during her lifetime.

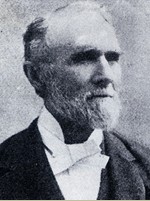

As many references to her photo note, the person she resembled was not some ballerina but Queen Victoria. That is a comparison that Tibbets herself laughingly admitted, as reported by her great-great granddaughter, Patricia Ortlieb, in a biography of Tibbets, which Patricia co-authored with Peter Economy.

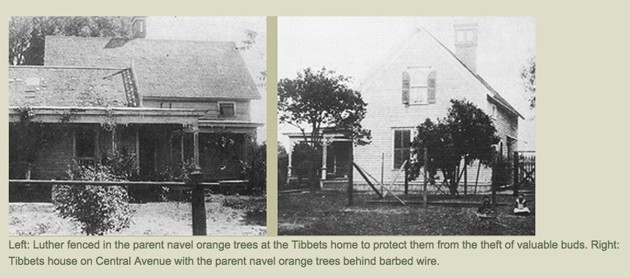

Tibbets is known to Riverside schoolchildren as the woman who brought the Washington navel orange to California. (My husband Jim confirms that as a fifth grader in nearby Redlands he was taken on a class trip to view, with reverence, the Parent Navel Orange Tree in Riverside.) Indeed, the entire California navel-orange industry originated with the two small trees that Tibbets planted outside her Riverside kitchen door in 1873. The industry changed the state and the region. In Riverside, the allied industries of irrigation systems, grove expansion, orange sorting and packing, and refrigerated shipping catapulted the town to boasting the highest per capita income in the entire U.S. in 1893.

Tibbets remains better known for oranges than for the social-justice causes she fought for during her unconventional life and which, presumably, were part of the reason she now has a statue on Riverside’s pedestrian mall.

Eliza Lovell Tibbets, born in Cincinnati in 1823, earned several labels. She was an abolitionist, who, along with her husband Luther Tibbets, tried and failed to establish a new colony for freedmen and whites in Virginia in 1867. She was a suffragist, marching with Frederick Douglass to Washington in 1871. She was a member of the Swedenborgian church, who followed mystic and scientist Emaneul Swedenborg. And she was a spiritualist, who became well-known as an accomplished medium for her sought-after séances as well as a fortune-teller for local fundraisers.

The lives of pioneers and immigrants always carry stories. Eliza’s stories reminded me of my own family stories, of relatives from Czechoslovakia, who were pressed to add a few of the village children to their own brood when they boarded a boat for America after the turn of the century. That is how one branch of my family ended up with at least two daughters named Agnes, who went by the names of Agnes1 and Agnes2.

Riverside was remote in the 1870s; you forded the Santa Ana River to San Bernardino when you needed to find skilled labor, and you drove a buckboard wagon a few days’ trip to Los Angeles when you wanted a newspaper. Luther Tibbets headed west first to get established in another utopian community starting there, based on ideals of political justice and a business model of growing fruit. A few years later, Eliza and the rest of her family took the train to San Francisco, then a boat to Los Angeles, and then a wagon to Riverside to join him.

The Riverside community struggled until they finally finished an irrigation canal. Just a few months into her settlement in Riverside, Eliza, searching for a stable cash crop for her family, contacted an acquaintance from her days in Washington D.C., a horticulturalist with the Department of Agriculture named William Saunders, who experimented with imported plants in his greenhouse on the National Mall. It was a serendipitous moment. Saunders had heard about a promising species of oranges from Bahia in Brazil. He received a dozen young trees, and grafted buds from them on to root stocks, two of which he sent to Eliza Tibbets at her request.

Thus began the story of Washington navel oranges in California. Part of the tale, apocryphal or not, is that Tibbets nurtured along the two little trees with used dishwater from her kitchen. The first fruit was picked in 1875, from the trees of Tibbets’s neighbors, to whom Eliza had sold buds to graft.

If you don’t get the point by now, the Tibbets couple was complex and unusual. Luther could be impetuous and was definitely litigious, and they were not the best financial planners. Instead of planting groves, they chose quick money by selling their buds for grafting. They also subdivided their land and sold off much of their property during the real-estate boom that accompanied the explosion of the orange industry. By 1882, half a million Washington navels were growing in California, all as grafts (essentially, clones) from the two original Tibbets trees.

By 1887, the real-estate bubble burst. Sound familiar? The Tibbetses continued their lifelong string of legal disputes and lost their remaining property in foreclosure. Eliza Tibbets died at a spiritualist colony near Santa Barbara in 1898. She was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Riverside, in a grave that remained unmarked until nearly a century later, in 1993.

Eliza Tibbets joins my personal list of unusual, strong, pioneering, and generally under-appreciated women whom I’ve learned about along our American Futures journey. Many of their stories made me wonder: Why had I not heard of them before? That is part of the reason I’ve wanted to write about them and keep their names and accomplishments alive.

In that spirit: you can read about the first woman who flew solo around the world, Jerrie Mock from Columbus, Ohio, and Caroline Henderson, a persistent self-made farmer who chronicled her survival through the Dust Bowl era for The Atlantic. Next up after Eliza Tibbets, an entrepreneurial Renaissance-woman, lifelong friend of Eleanor Roosevelt, and first Congresswoman from Arizona, Isabella Greenway.