Thirty years ago, Pittsburgh was an American urban nightmare: horrible air pollution, dirty rivers, fast-spreading decay, plummeting employment, and massive out-migration. Look it up. It’s not a pretty story. But that was then.

We were in Pittsburgh recently for the American Futures series and can attest to what anyone who’s been paying attention for the past 15 years already knows: The City of Bridges is no longer an urban nightmare; in fact, it’s an urban model. It’s a city with clean air, beautiful riverfronts, an attractive downtown, a thriving arts scene, world-class universities, a vibrant tech sector, affordable living, and much more. In the days ahead we’ll have more to say about the cultural arts and the tech sector there.

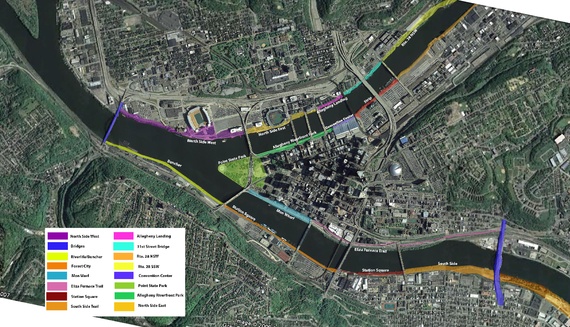

Today’s topic—the revival of this city’s famous riverfronts—is a well-known story, but one worth reviewing, both in testament to how far Pittsburgh has come with its waterfronts and in tribute to its unrestrained ambitions for their future.

But by the 1970s, the city and its people had paid a heavy price for all that. The riverfronts were essentially a wasteland, closed off to residents by industrial sites, railroad lines, and highways that lined the waterfronts along each side and made the rivers inaccessible to people. The areas near the rivers were dangerous, polluted, blighted. “Be home before dark and stay away from the rivers,” parents are said to have warned their kids on summer afternoons.

A tentative, early nod in the direction of paying more respect to Pittsburgh’s waterways and riverbanks had come after World War II with the creation of a park on 36 acres of land at the point where the Allegheny and Monongahela converge to form the Ohio, replacing an industrial slum and rail yard that occupied the land. It took decades of work to transform the area. Point State Park finally opened in 1974 with a now-iconic fountain at the very tip, a symbol of what the city could do to revive itself more broadly if it had sufficient will.

It took another 25 years for the next big step on behalf of the rivers. And that came with the creation in 1999 of what was then known as the Riverlife Task Force (since 2008 known simply as Riverlife), an advocacy organization that is responsible for much of the good that has occurred along the riverbanks in the past fifteen years.

The Riverlife Task Force “combusted into being,” says Lisa Schroeder, President & CEO of Riverlife, and brought together in a public-private partnership a broad array of actors committed to the transformation of the waterfront: local political leaders, philanthropists, business people, property owners, and advocates for planning and design. They all saw what Schroeder describes as a “once-in-a-century opportunity” to do something big and good for the city.

The opportunity—the combustible material—was a major urban initiative, at the time already well along in the planning and design stage, to replace the old Three Rivers Stadium on the North Shore with two new stadiums (one for the Steelers and one for the Pirates) and to build a new convention center on the South Shore. If done right, these projects could transform a big downtown stretch of the Allegheny. But if done poorly, they could keep these large stretches of riverfront essentially sealed off from public use for another hundred years.

The very first time the task force convened was on a river boat tour. David McCullough, the author and historian – and Pittsburgh native – was brought in as a featured guest to speak to the group. His remarks are still memorable to those who were there, and this passage in particular stays with many who heard him:

Don’t make it like other places, because Pittsburgh was never, ever like other places. Make it a place where people want to bring those they love…Make it a place for music and sunshine and trees by the water. Make it possible to walk out of an office building down to the river, or to bring your family to a picnic by the river. Think of it on as large, as ambitious, a scale as you possibly can.

And they did. The task force, at the urging of then-mayor Tom Murphy, got heavily involved in the planning and design of the North Shore projects, but because all that was already well underway, it took a lot of creative thinking and advocacy on the part of the Riverlife Task Force to move the development grid back off the rivers to provide a whole new level of greenspace, tiered promenades, boat landings, family-friendly amenities, and access passageways every 400 to 600 feet connecting the riverfronts with the neighborhoods beyond.

Moreover, knowing that it was critically important for their vision of the riverfronts to be in the interest of the people who owned the property, the task force members included among their founding members Art Rooney, owner of the Steelers, and Kevin McClatchy, then owner of the Pirates. Getting them on board was crucial.

And to avoid the mistakes of countless earlier urban redevelopment initiatives around the country, the task force members understood that the public, clamoring for involvement in the planning process, had to be brought into the mix as a major stakeholder group. The task force hired Alex Krieger’s Boston-based architectural design firm to create a master plan for Pittsburgh’s downtown shoreline. Krieger’s firm conducted hundreds of public meetings throughout the Pittsburgh community, seeking input, and encouraging residents to dream big about what could be done.

Krieger’s award-winnning master plan for Three Rivers Park, presented in 2001, envisioned a grand urban river park that would connect the rivers to neighborhoods, make the waterfront an inviting front door to the city, and border the rivers with dramatic and appealing architecture.

That was the key moment. This could well have become one of those situations where a task force’s efforts result in nothing more than a nice coffee-table book of plans and artists’ gauzy renderings. But here’s where what has emerged as “the Pittsburgh model” of river renewal kicked into gear in a big way: the foundations—realizing that the Task Force was asking for a deeper level of investment, a more patient approach, and a new, higher standard—collectively invested $14 million into the capital construction of North Shore Park (a $40 million project).

Now there is a new “entertainment district” along the North Shore, with a baseball stadium, a football stadium, science center, and a casino—and the convention center along the South Shore. The physical transformation is enormous. Schroeder summarizes another impact: “What that project demonstrated was that by making a deeper investment up front in open space, all of the property became automatically more valuable.”

The recently reconstructed Point State Park is another triumph for Riverlife. The park had suffered a lot of wear and tear over the past several decades, so looking toward Pittsburgh’s 250th anniversary in 2013, Riverlife was asked to spearhead a campaign to renovate the point. The park previously had not been connected to downtown on the water’s edge, but with determined advocacy from Riverlife, that now has happened. And a subtle but important change was made to the plaza surrounding the iconic fountain by adding a stepped rim where people can sit, mingle, and enjoy the view. The refurbished park is really stunning.

These and other accomplishments are real. But Riverlife’s ambitions extend to 13 miles of riverfront in Pittsburgh, so the continuing effort to improve quality of life along the rivers will go on for many years, with some of the most complicated, opportunity-filled projects still ahead. For example, the so-called Strip District Riverfront Park project, now under way, is one of the largest riverfront developments undertaken anywhere in the United States. Schroeder told me: “We’re looking at more than 20 blocks of riverfront. So, that is a full-scale, game-changing opportunity to open up a riverfront and connect it to the dynamic community beyond it. It’s going to be as big as anything we’ve done so far.”

The linear footage and acreage of the projects are impressive. But more breathtaking is Riverlife’s juggling act as it tries simultaneously to attend to a broad mix of important values and goals:

- Making Pittsburgh more walkable and bikable by including pedestrian bridges, continuous bike-pedestrian connections, riverfront trails, and comprehensive signage;

- Attending to important environmental concerns: riverbank stabilization efforts to restore habitats and riparian ecology; “green infrastructure” that addresses problems with the region’s combined sewage and stormwater overflow;

- Creating recreational and other attractions such as fishing piers and marinas, paddleboat and kayaking kiosks, shops, restaurants, and playgrounds.

Every project is different geographically and in terms of land use, but Riverlife’s mission with each project is to maximize all of those values and considerations noted above. Schroeder told me, “We start from scratch with each stretch of riverfront, working with the vested interests on what needs to be accomplished. What we try to do is raise the lens up to say, ‘What will happen here anyway—through natural forces of the market, through the goals of the property owner—and what won’t happen?’ We see Riverlife’s job as taking on what won’t otherwise happen.”

“We’re working to create open, metropolitan space that includes amenities for people of all ages, so that the riverfronts become the center of community life—a rich, public destination.”

And it’s happening. Not merely because of the skillful advocacy of Riverlife’s leaders, though that surely has helped. Rather, Pittsburgh has some special and unusual elements that have positioned the city to achieve what it has. The most important of these is the prominence of the city’s foundation sector. The public sector has been supportive politically, but Riverlife has had to figure out how to achieve its goals largely without government dollars. That’s where the foundations have been key.

Lisa Schroeder told me, “Most of our time is spent constructing partnerships and figuring out what we can do to incent people to reach to the highest level. The answer is very distinct with every project.” Pausing to look out over the rivers her organization has transformed, Schroeder continued, “The model we’ve pioneered evolved out of necessity. It’s not the easy way to do things, but it’s resulted in a lot of good.”