“One half dream; one half plan.” That’s how one student described his life at the Governor’s School for the Arts and Humanities in Greenville, South Carolina.

Dreaming big at the Governor’s School means Broadway, Hollywood, Carnegie Hall, Pulitzer, Pritzker. Planning big means half of every day in practice, rehearsal, studio, workshop, training, rewrite, instruction, all alongside standard high school academics.

The 240+ South Carolina students are a natural match with this very specialized residential school. They steep in their identity and passion as young artists. (There are 5 arts tracks: dance, drama, visual arts, music, and creative writing.) “You’re a dancer from the minute you get up in the morning,” is how the dance teacher describes her students. “This is how I think of myself. Dance is the place I go to work through my issues. I am comfortable here,” say the students about themselves. They are so mature and accomplished that it is easy to forget they are teen-agers, until they start talking about prom, or offer their alternate self-description as “quirky”, or mention how they really, really miss the puppy at home.

The Governor’s School was founded as a summer program in 1980, by musician, teacher, and reputed force of nature Virginia Uldrick. Her vision was to create a non-traditional arts conservatory. The county and city of Greenville won the derby for permanent home for the expanded, school-year campus. They donated more than 8 beautiful acres, the former site of the Furman University men’s campus, which overlook the now bucolic Falls Park and Reedy River. The 27 million dollar campus, which is named for Uldrick, opened in the fall of 1999 to its first class of juniors. You can reach the school by road, or much more fun, by the Swamp Rabbit Trail along the river and leading up to a (locked) gate at the bottom of the campus hill. It’s a five-minute walk to the Peace Arts Center, Spill the Beans (Coffee! Ice cream!), and all the other offerings of Greenville’s revitalized Main Street. The school’s first encore is already underway—a major capital campaign for a new visitors center, which will include a gallery and gardens.

The students, juniors and seniors (and sophomores, if they are dancers), are admitted from all around the state, from tiny towns like Little River, population 9000, to larger ones like Greenville and Columbia. Some arrive with impressive portfolios or experience in the Governor’s School summer programs. Others are “discovered” in the old-fashioned way through the deep digging and travel by admissions outreach. I asked the veteran teachers about changes in the students that they have seen over the course of their own careers. Now, they said, they are finding fewer kids with experience and their own sense that they have artistic talent. This means that recruiters today have to look more for the potential and less for the proven. The reason? Budget cuts, they said, which means less of the arts in schools and less exposure for the kids. Chilling.

A tour around the school is an experience. There are multiple dance studios, a performance hall, art spaces for silversmithing, ceramics, a brass foundry, studios for drawing, music practice rooms, a computer lab for graphic design, a gorgeous library, ad lib practice areas. I’m sure I have forgotten others.

You have to wonder about the stress level in such an intense living environment for high school kids. Lots of talented or accomplished kids have an awakening when they get to college that they’re no longer top-dog, or “everything and a bag of chips” as a writing teacher here described it. For these kids, the realization comes earlier, and it is accompanied by the rigors of their pre-professional endeavors. I saw and heard a few things about their reactions.

Several kids talked about synergy, rather than competition. They described how they’re all driven toward the same goal, and they can feed off that sentiment. “You feel it in the air,” one described, “to do something great.”

I asked about another sign of stress, eating disorders. The topic is out in the open, was the answer, and it has to be in a school with lots of ballerinas and actresses. Addressing this begins preventatively, with teaching awareness of a healthy lifestyle. That is accompanied by a watchful eagle eye, and backed up by a confidential “honor system” so friends can bring up concerns about friends to the counselors and advisors. “Of course it happens,” the administrators told me, and they need a strong support system around it.

There are two more interesting data points about the make up of student body and the challenges of the admissions work, which are food for thought.

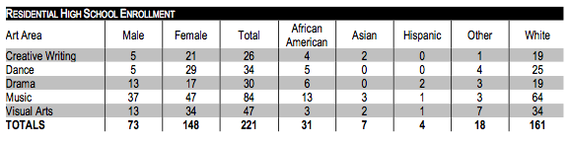

First, gender differences: some 63% of the students at the Governor’s School for the Arts and Humanities are girls. The gender ratio imbalance is most remarkable in dance and least remarkable in drama. The school reports that it seeks to build a balanced class in as many respects as they can, but a reality sets in. “If you need a bassoon player,” one told me, “you hope you find a boy, but it will probably be a girl.”

By contrast, at the South Carolina Governor’s School for Science and Math, established in 1988 in Hartsville, South Carolina, the student population is now evenly divided between boys and girls.

The A.J. Whittenberg Elementary School for Engineering, the public school in inner city Greenville, which I wrote about here, is 57% boys and 43% girls.

And second, socioeconomics: about one third of students qualify for free or reduced lunch, an accepted proxy for poverty status. I was told that the school attracts mostly lower and middle class students. The school is a harder sell to kids from wealthier families, they said, who don’t want to give up their rooms, cars, and TVs.

So where does this all lead? A reminder, the school graduated its first class a dozen years ago. But already, the recognition is flooding in. National Merit finalists, Presidential Scholars in the Arts, 100% acceptance to colleges or professional schools, including RISD, Juilliard, Guthrie, Eastman, Peabody Conservatory, award of all sorts. Interestingly, several students and teachers alike told me that there really is no pressure on the students to make a life in the arts. If you want to be a rocket scientist after all, that is fine. Last year 109 students earned 26.5 million dollars in scholarship offers, which breaks down to an average of a $243,000 offer per student.

And other dramatic wins fall within in a less celebrated spotlight. I heard a poignant story of one Govvie, as students are called, a young clarinetist who couldn’t afford his own instrument. When a local patron, fond of the school, heard of the need, he dug from his attic a beautiful clarinet, which he gave to the young man.

Perhaps the biggest accolade so far is returned to the school: one young woman told me effusively, “I love my school so much. I love the challenges. I feel at home while I’m here.”