I began visiting Greenville, South Carolina, schools more than two years ago, for our American Futures project. One was the A.J. Whittenberg Elementary School of Engineering, for the tiniest engineers in pre-k through grade five, which I wrote about here. At the time, I heard about plans for a middle school, set to locate adjacent to Clemson University’s International Center for Automative Research (CU-ICAR) campus and research facility.

When we returned to Greenville last week, I paid a visit to the new school, the Phinnize J. Fisher Middle School, named for a former superintendent of Greenville County Schools. Fisher opened in fall 2014 with a class of over 300 sixth-graders. Today, Fisher enrolls sixth- and seventh-graders. Next year, Fisher will have the full complement of students in grades six through eight. Some of the tiny engineers from A.J. Whittenberg—growing up now—attend Fisher. Others go elsewhere. Greenville County schools operate on a “choice” system; essentially, students are assigned to the school in their home district, but they can apply and join the lottery to attend a different one. About 15 percent of Greenville students attend “choice” schools.

Several folks in Greenville told me, with a kind of we-love-all-our-children-equally tone, that they could recommend any number of schools for me to visit in the county: magnet schools, STEM schools, charter schools, IB schools, New Tech schools, etc. Of course, I couldn’t begin to visit them all. Fisher, the school I chose, is an appealing school to visit; it is unconventional and surprising, especially for those of us used to more traditional schools. “Is that a school?” is a question that Principal Jane Garraux says she hears that people often ask as they drive by.

Creating a culture. Jane Garraux had been planning to retire after her 30-plus year career in Florida’s Miami-Dade district, where she had already founded two schools. Then she began hearing about Fisher Middle School opening in her hometown of Greenville. She was enticed into being a founding principal for a third time and set to work building another school.

Fisher’s STEAM curriculum is taught through a method called project-based learning (PBL). It is a holistic approach that encourages collaboration, critical thinking, creativity, problem-solving, and so forth.

Greenville’s business community, collaborating with the education community, spoke up in favor of developing the soft skills that come with this approach. Nurturing a future workforce that was not only steeped in the world of technology, but was also comfortable and practiced in communicating, teamwork, organizing, public speaking, etc., would be critical to the kind of workforce they would be looking for.

For starters, Garraux needed an entirely new faculty and staff. She drew from all around the country as well as Greenville looking for enthusiasm, dedication, flexibility, and for buy-in to hone their skills with PBL. While PBL has been around education circles for a long time, many of the teachers would be new to the method.

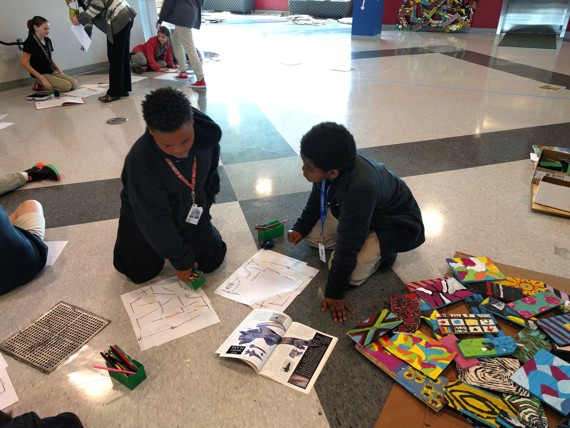

So how about a look at a seventh-grade social-studies project through the STEAM PBL lens:

Anne Kelsey-Zibert, a veteran teacher of 12 years and newly trained PBL teacher, took me step by step through an example of project-based learning in her class. The students were studying WWI, and in Kelsey-Zibert’s mind for the students it was connecting what it was like to live during the times to actual events they were studying. The students would construct a tool or artifact of the era, using today’s materials, and then present the object to the class. This exercise would fold in research, design, construction, writing a presentation of their creation in relation to the historical event, public speaking to the class. In addition, in a kind of shark-tank twist, each student received $1,000 (fake of course) to invest their favorite, most-promising project.

Another strong piece of Fisher’s culture is the open door to the community. People in the business community are more than in conversation with the education community—they are participants.

At A.J. Whittenberg, I watched employees from General Electric teaching classes about electricity. At Fisher, employees from Michelin were there the day I visited, demonstrating catapults to the middle-schoolers. ZIKE, a Greenville company that makes a human-powered hybrid scooter-bike, donated 20 bikes to the school. Wynit Print Distribution and Leapfrog Printing donated a 3D printer. Clemson offers tours and mentorship programs to Fisher, and some Clemson faculty hold regular office hours for Fisher faculty on the campus. These and many more partners are investing in these middle-school kids and piquing their interest even now.

What does that mean? One key is flexibility. A walk around Fisher could look different even during the course of the day. Classrooms have big glass-paneled garage doors, which can lower for a cozier space or rise to create an open space with adjoining common areas. There are indoor-outdoor classroom spaces and an innovation lab so big that you can drive a car straight into it.

Once, when rain would have canceled an outdoor bike demonstration, the show moved indoors, using some big existing spaces and creating others by opening the garage-size classroom doors.

The school is bright and airy. The innards of the building are exposed: brightly painted exposed pipes, color-coded for their functionality and a see-into server closets. Students work in red, blue, or green learning communities. There are studios, design labs, arts-and-media centers, collaboration and seminar rooms. There are no student lockers; students have little to store because they are all given laptops, which hold their books, papers, homework, you name it. They carry backpacks, plenty of which I saw strewn around.

The day I visited, huge winds were blasting through in the wake of fierce rainstorm. Outside, clusters of sixth-graders were picking up and patching together shelters they had designed and built from foraged found-goods—cardboard, plastic bags, wooden pallets, old newspapers. (The cardboard is hard to come by these days, explains Critell, since it commands $400 a bale in the recycling industry.)

The overnight storm had wreaked some havoc, injecting, no doubt, a big dose of reality as the students must have considered how lucky they were not to have camped out in their shelters. These issues were on the students’ mind, as they were concurrently reading a popular novel called Maniac Magee, about an orphan looking for a home, and woven with themes of homelessness and racism. They also learned that the location of some of their shelters, a protected-looking corner near the outdoor amphitheater, actually turned out to be a wind tunnel.

This kind of teaching and learning takes time. Can you imagine squeezing it into a 45-minute period? Everyone at Fisher talked about their block schedule, with the 90-minute classes, meeting twice each week.

A byproduct of this schedule is capturing an extra period which can be devoted to the arts, opening up a lot of options for student to pursue as electives. Fisher offers, for example, broadcast journalism, video game design, forensics, robotics, all sorts of music, art, and drama, and more.

Think back, if you dare, to your middle-school years. Frankly, I remember junior high, as it was called, as the worst years of my life; social life was mean and academics were boring. I know that my husband, Jim, spent his in a few different schools, because it wasn’t his best time either. One of our sons spent part of his middle school in a Japanese public school, wearing the Prussian-style black uniform that Japanese kids still wear today. Even the name, middle school, is non-descript and probably best forgotten, suggesting time squeezed in between childhood and high school, which both have a more positive ring to them. Learning about Fisher Middle School was therefore, for me, quite astonishing. Instead of letting those years slip quietly by, Fisher is seizing the years and helping students make much of them. Hats off to them.

If you’d like to see more of the school, please watch this video.