For those joining us late: California’s controversial High-Speed Rail project is worth paying attention to, no matter where you live. While everyone moans about America’s decaying infrastructure, this is the most ambitious and important infrastructure project anywhere in the country. Its outcome has a bearing on Jerry Brown’s current campaign for a fourth term as governor. It also shows something about our governments’ ability to undertake big, complicated efforts—and our public ability to discuss and decide on these issues.

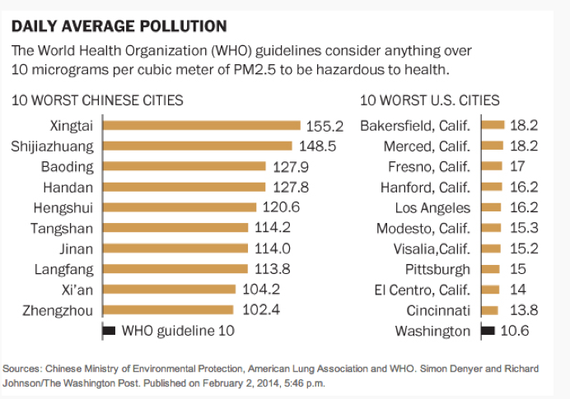

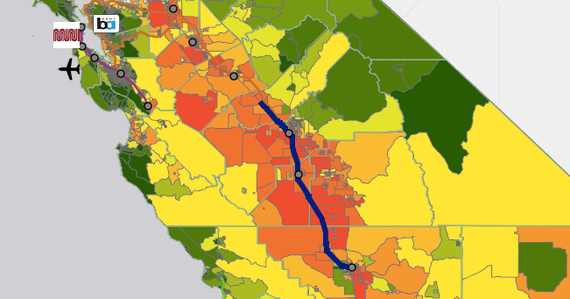

But the place where people are already paying closest attention is California’s Central Valley, where the first links in the north-south chain would be laid. As everyone in the state knows, the broad valley that runs from near Redding in the north to Bakersfield in the south contains some of the world’s most productive agricultural territory. It also contains many of California’s most distressed communities. If the recent suggestion to split California into six separate states ever took effect, which it won’t, the new state of Central California would likely become the nation’s poorest, replacing Mississippi. People in many of these communities also cope with the nation’s most polluted air. As a reminder, from a chart I’ve used before:

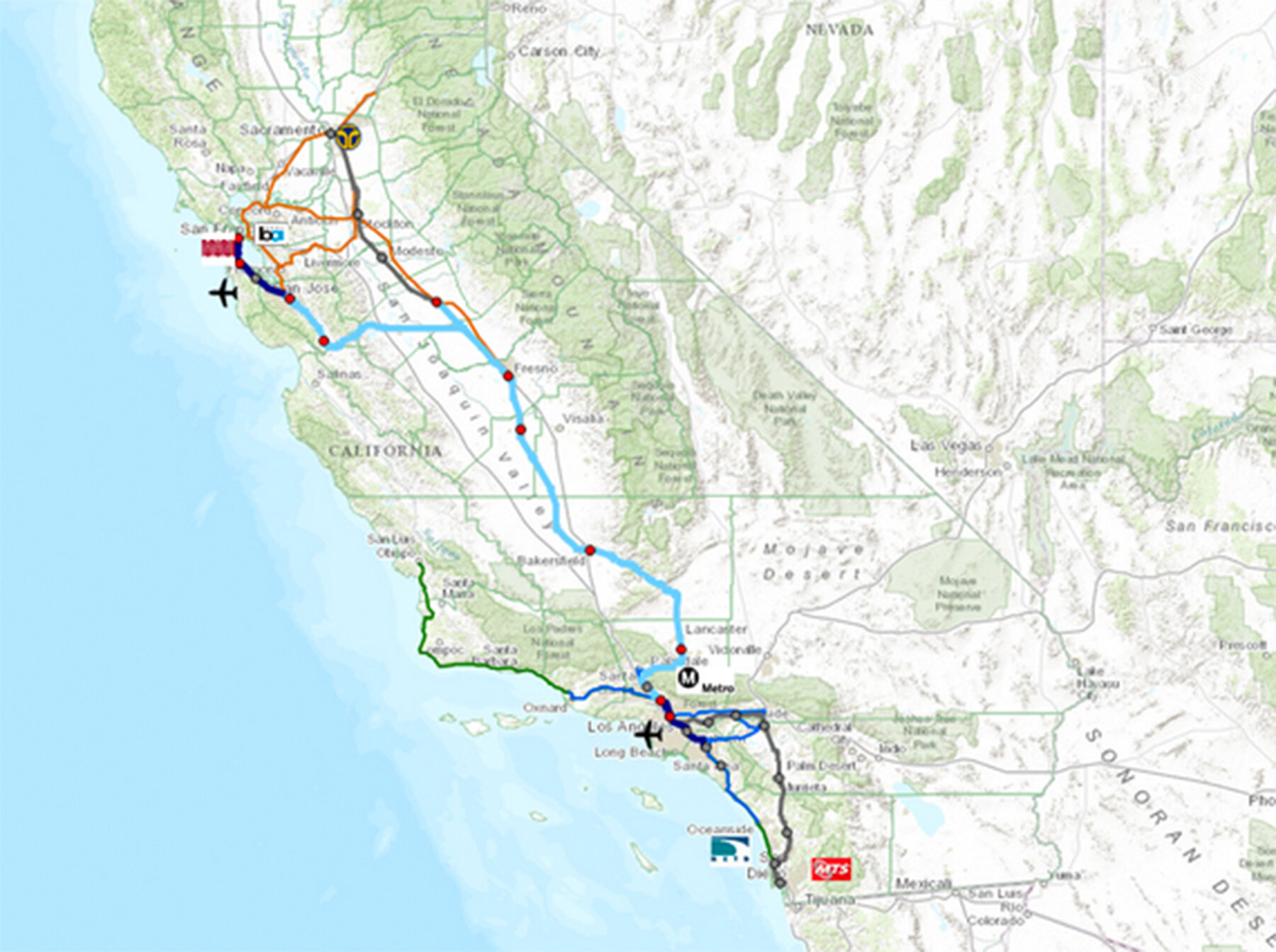

Dan Richard, chairman of the High-Speed Rail Authority explained early in this series that for legal, technical, and financial reasons the construction would not begin in the population centers of LA or San Francisco. Instead it would start by connecting points within the San Joaquin Valley, which is the part of the Central Valley running from the Sacramento area south toward Bakersfield. Some farmers there are bitterly opposed to the project, saying that it would cost too much precious farmland. Richard and others contend—convincingly, from my point of view—that more farmland will get chewed up by road-building and sprawl if the state does not develop a viable rail option. For now, let’s hear from some readers in and around this part of the state.

1) The benefit will be greatest in areas that really could use the help. From a reader who works in Fresno, the largest city on the inland north-south route:

I recently read part 5 of your series on the California High-Speed Rail project and noted a glaring omission – no reader was from the San Joaquin Valley (SJV).

This matters to me because I live in the SJV (reside in Tulare, work in Downtown Fresno) and I believe that one of the most compelling arguments for the project are the huge benefits HSR will have on SJV, one of the state’s fastest growing regions. The current population of the SJV is just under 4.1 million, which by itself exceeds the population of 25 other states in the country.

Most of the readers that do not support HSR in your piece, and a popular topic among critics, mention the L.A to S.F commute. Now, while Prop. 1A mentions the non-stop requirement from L.A to S.F, the greatest utilization of HSR, in my opinion, will be the much shorter trips (i.e. Fresno to S.F, Bakersfield/ Palmdale to L.A).

The cost-benefit of this project is much greater for the SJV cities. They will be connected like never before to the state’s major metropolitan areas. Tedious drives with a roundtrip travel time of 6-8 hours will be reduced to 3 hours. Neglected city cores will be redeveloped, new businesses will move in, residents will have the opportunity to seek new job opportunities in S.F/L.A, and most importantly all of this will be the game changer the SJV needs to diversify it’s agriculture based economy.

The SJV, even during good times and in wet years, suffers from chronic high unemployment, usually double-digits. In order for California to succeed, this region of 4 million people also needs to succeed. HSR provides that opportunity through the new long-term jobs that will be sparked by HSR and the stations located in the city cores. The SJV usually gets neglected in Sacramento and here’s a perfect opportunity to get noticed.

For me, this is the main reason why I believe that the California High-Speed Rail is vital and necessary to California’s future.

2) Isn’t California going to need some big new transport anyway? From a reader in the home city of the University of California’s latest branch:

I live in Merced, with strong ties to both the Bay Area and San Diego. A couple of things that I’m curious about, that I think would make a big difference in this debate

1) Airports. How much more growth can Bay Area and Southern California airports support before we need to spend billions of dollars on some type of infrastructure project? Are existing intrastate flights crowding out connections with Asia? It seems like that could have huge ramifications for the California economy.

2) Central Valley demographics. People envision High Speed Rail as a pet project for liberal elites…but between Bakersfield and Modesto, it seems like the greatest demand would be from people who don’t take car ownership for granted, and definitely not one car for every adult member of a family. Is that what’s already driving Amtrak’s California routes to be some of the most heavily used in the country?

And many of the people writing in seem confident that Central Valley jobs are so diffuse that no train station could be conveniently located for commuters…but is that actually the case? I honestly have no idea where most people work in Merced, but a lot of major offices seem to be located downtown.

3) Rail travel time is “good” time. Travel by car or air is not. From a reader in the SF Bay Area:

As a CA resident, [these exchanges are] changing my thinking about the value of HSR. Still concerned about many of the obstacles presented, but the point about leveraging land development near the stations and right-of-way rights along the route was new to me.

One relevant aspect that I don’t see being included is an assessment of relative productivity between the travel options. As a former resident of San Luis Obispo I often took AMTRAK to LA and San Diego when its schedule happened to align with mine (not nearly as often as I’d have liked due only one trip a day without getting on/off a bus connector) and now as a resident of NORCAL I often commute into SF via the ferry from Vallejo.

In both cases I found my productivity during the travel to be very high — comfortable seats, tables available, able to walk/stretch periodically, food service, WIFI (not-so-much on AMTRAK but iPhone hotspot solves that shortcoming), not to mention pleasant scenery going by — that what appears on paper to be a long commute is transformed into a “What? At my stop already?” highly productive and enjoyable experiences. There’s no comparison to the level of productivity when traveling by car or commercial airliner.

As before, I’m mainly quoting readers rather than arguing or annotating along the way. But let me underscore the final point in this reader’s note.

Three hours door-to-door for a plane flight, versus three hours on a train, sounds like the same time-cost for getting where you’re going. But in reality they’re entirely different experiences. Much of your time for air travel is “bad” time. You’re in a cab on either end, you’re waiting in an infinity of lines in between, you have all the other charm-free elements of today’s airline experience. If you’re driving, it can be more enjoyable, but you’re not supposed to be reading, typing, etc. By contrast, nearly all of your time on a train trip is “good” time, even allowing for the cattle-car experience of waiting to board at New York’s godawful Penn Station.

From another reader on just this point:

I have for years commuted on the Amtrak San Joaquin from the Bay Area to my home near Yosemite.

Got no complaints. WiFi works. People are nice. Serviceable bus connection to Mariposa/Yosemite at Merced. No complaints. The bullet train will not really cover that route, but I don’t care.

And still on this point:

I took the Tokyo to Osaka “bullet train” in 2000, and this week, I took the DB ICE train from Frankfurt to Stuttgart. If the LCD display hadn’t shown our speed (240 Km/hr), I wouldn’t have known it — the ride was that smooth.

The post-WW II explosion of the suburbs really complicates intra-metro light rail, but we certainly have a case (IMO) for more inter-metro high speed rail to reduce ground and air traffic congestion.

4) “We’ve effectively paralyzed ourselves.” To round things out for now, a reader outside California on the larger political questions the project raises:

I think one thing that stands in HSRs way, not just in California but nationally, is that our system has too many intentional and unintentional choke points, so that we’ve effectively paralyzed ourselves.

Eminent domain proceedings are expensive (as is the land that the project will sit on) and time consuming, and there are enough ways for community organizers of both the positive and negative sort to kill most projects via NIMBYism or on other grounds.

While we’ve pulled off several impressive civil engineering feats recently, we haven’t, as far as I can remember, done anything really new, in the sense of expanding capacity, in perhaps the past twenty years. Most of the major civil engineering projects have been replacements or augmentations of existing (pre-1980) infrastructure, along with some infill development to expand capacity on pre-existing things.

As I say, I think a large part of this is because we have too many kill points built into our system, so that it’s almost impossible to achieve the consensus necessary to build a truly new project. However, there are two other important factors that I think also explain our lack of “new” infrastructure.

First, we already have picked a lot of low hanging fruit. China and the rest of the developing world can absorb a lot of new highways and the like, because they’re building from scratch. We already have a well built highway system, with Interstates that extend to even the most remote areas of the Dakotas and Montana, linking all of our major and most of our minor cities. Our rail system is terrible for passenger traffic, but for freight, it’s second to none in terms of efficiency, thanks in part to our large loading gauges.

Secondly, disruptive infrastructure is more disruptive when it’s disrupting something valuable, and we have a lot of money tied up in existing infrastructure, to the point that it’s prohibitively expensive to reroute things.

Consider the Tappan Zee bridge, which was originally located where it was in order to circumvent the Port Authority’s jurisdiction on trans-Hudson bridges. The replacement bridge, which is scheduled to open in 2018, stands right next to the original, because trying to use the more efficient southern routing was deemed too expensive and disruptive, so they just repeated the mistakes of 50 years ago.

Indeed, this is a large part of why the CA HSR project is supposed to go to the city limits, rather than the city center. Starting to tear up houses and apartments at $1M and $2M a pop gets very expensive very quickly, especially when you have people who are fighting it in court…

Finally, I think there is some justified skepticism about how the government, especially at the state and federal level, contracts and supervises these projects, especially in terms of cost control, though this problem isn’t unique to those levels of government, or to civil infrastructure projects in general… Perhaps the new overachievers in local government that you referenced in one of your prior posts will be able to make headway on this.

Nonetheless, I do think you’re right that large infrastructure projects are often criticized more harshly than perhaps they should have been, particularly in terms of their societal merit, since most infrastructure projects don’t capture the full value of the benefits that they create (nor should they).

For the record: This post is No. 6 in a series. See also No. 1, No. 2, No. 3, No. 4, and No. 5. Also see the interactive map showing different planned construction phases of the project, put together by UC Davis, the HSRA, and the mapping team at Esri.