Yesterday in Sacramento, Jerry Brown was sworn in, at age 76, for his fourth and final term as governor of our most populous and economically most important state.

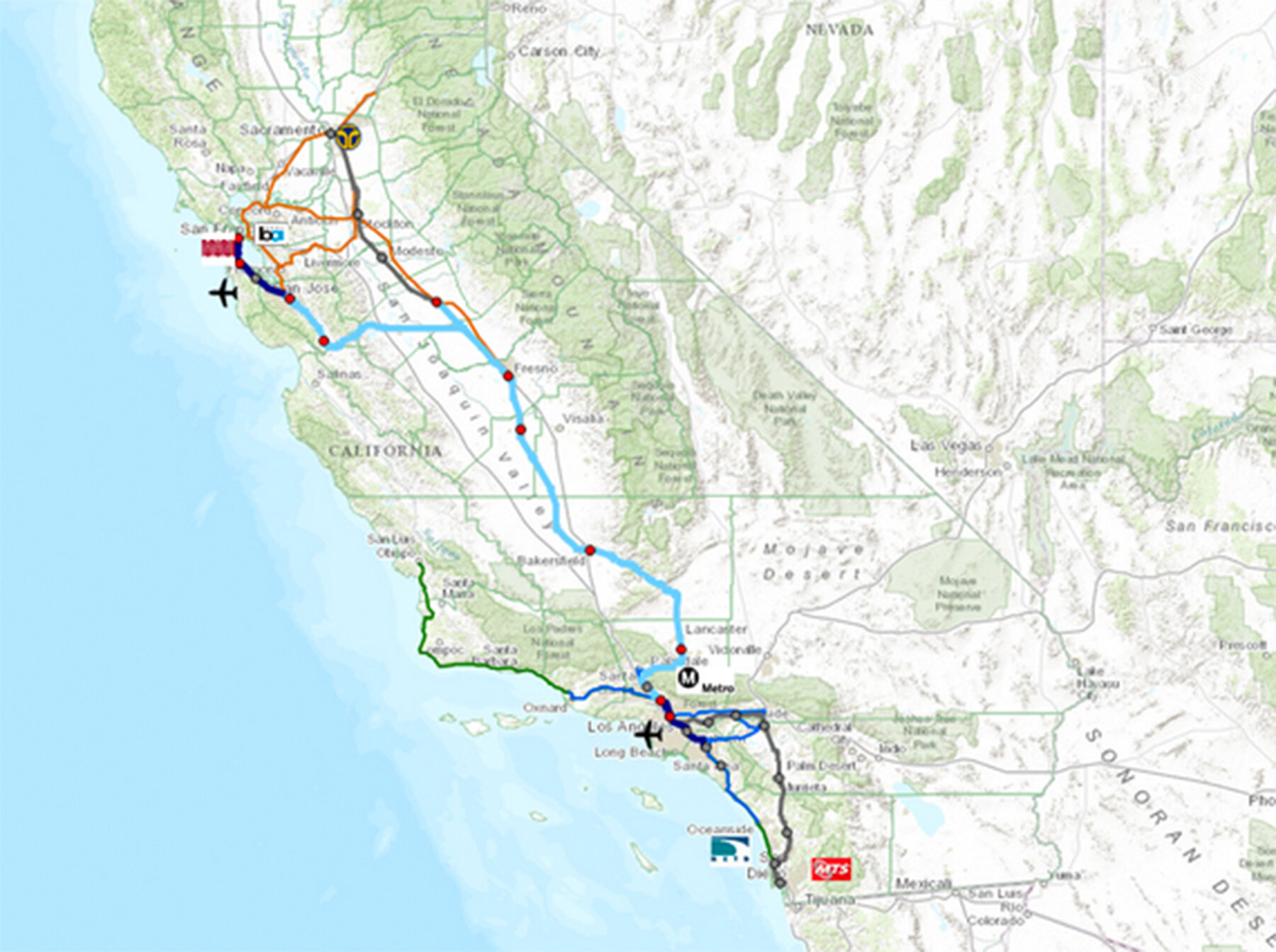

Today in Fresno he will preside at a symbolic groundbreaking of his major infrastructure project as governor, and the largest one underway anywhere in the country. This is a north-south high-speed-rail program that will start construction in the state’s hard-pressed Central Valley region and ultimately link the great population centers of the San Francisco Bay Area and the Los Angeles basin.

For reasons I described in this 2013 article, I think it’s good for California, and good for all Americans’ understanding of politics, that Brown has been returned to office for these four last years. For reasons I have laid out in, um, copious detail, I also think that it is good for the state and the country that this project go ahead. (For the details, see episodes No. 1, No. 2, No. 3, No. 4, No. 5, No. 6, No. 7, No. 8, No. 9, No. 10, No. 11, No. 12, No. 13, No. 14, No. 14 1/2, and No. 14 3/4. Today’s item is officially No. 15, and is The End of the Line.)

And if you go ahead to roughly 23:00, you will see Brown talking about his high-speed-rail project. It gets a cheer, but to be fair, it’s a secondary theme in the speech, which goes in more detail into Brown’s plans for education, prison reform, and environmental protection. If you’re wondering what it’s like to talk with Jerry Brown, the speech as a whole (full text here) will get you started. As I mentioned in my article, the autumnal Governor Brown peppers his formal statements and informal comments with references to his family’s many generations in the state, and the state’s unusual position in the nation. That’s also how he ended this speech:

Whether the early explorers came for gold or God, came they did. The rest is history: the founding of the Missions, the devastation of the native people, the discovery of gold, the coming of the Forty-Niners, the Transcontinental Railroad, the founding of great universities, the planting and harvesting of our vast fields, oil production, movies, the aircraft industry, the first freeways, the State Water Project, aerospace, Silicon Valley and endless new companies and Nobel Prizes.

This is California. And we are her sons and daughters.

Yes, California feeds on change and great undertakings, but the path of wisdom counsels us to ground ourselves and nurture carefully all that we have started. We must build on rock, not sand, so that when the storms come, our house stands. We are at a crossroads. [JF note: This “crossroads” sentence is in vapid contrast with the rest and could have been cut.] With big and important new programs now launched and the budget carefully balanced, the challenge is to build for the future, not steal from it, to live within our means and to keep California ever golden and creative, as our forebears have shown and our descendants would expect.

* * *

1) America is direly short on infrastructure; the financial and political resistance to remedying that is powerful (for reasons Mancur Olson once laid out) and usually prevails. China is biased toward wastefully building infrastructure it doesn’t need. The U.S. is biased the opposite way. So when there’s is a real chance to build something valuable in America, I start out in favor of it.

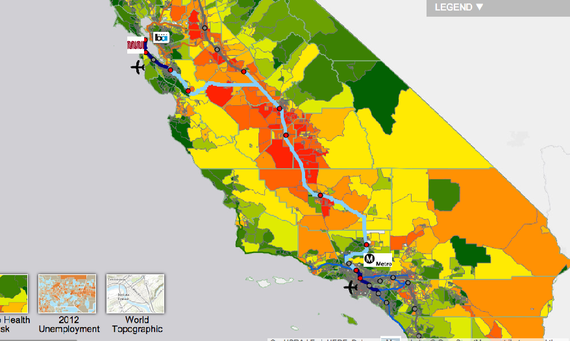

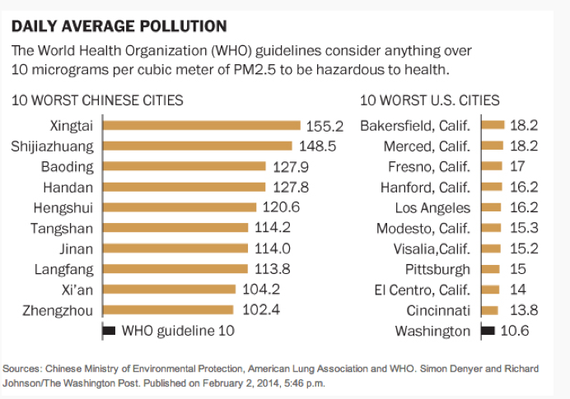

2) The counties of the Central Valley of California, where the first stages of the construction will begin, are not just the poorest part of a rich state but also, taken on their own, would constitute the poorest state in the entire country. Of the five poorest metro areas in the United States, three are there. Most dynamic analyses of the effects of the rail project indicate that it would bring new jobs to a region that most needs them, while chewing up less farmland than normal sprawl and freeway expansion would destroy. Which leads to …

And, maybe the biggest factor of all:

4) There is an established track record of overestimating the problems of big infrastructure projects, and short-sightedly under-envisioning their benefits. Here’s the crucial contrast with big military construction projects I’ve written about recently. Repeatedly, big military projects have come in over budget, past schedule, and below performance promises.

Repeatedly the opposite has been true of big national or regional infrastructure projects. Their drawbacks have been exaggerated before they’ve been started, and their potential benefit has been grossly under-imagined. Here’s a few of the projects that seemed impractical, quixotic, ruinously expensive, or not worth the bother when proposed:

- The Louisiana Purchase

- The Erie Canal

- “Seward’s Folly” of buying Alaska

- The Transcontinental Railroad

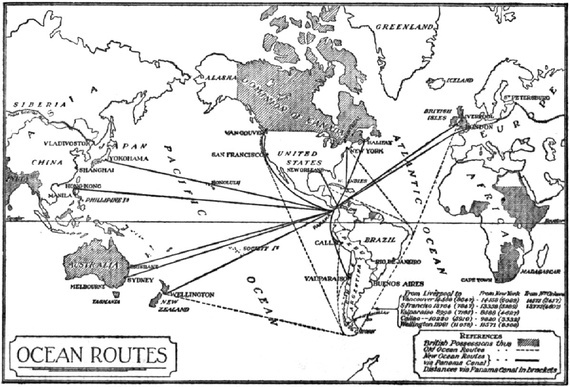

- The Panama Canal

- The Golden Gate Bridge, and the Bay Bridge

- The TVA, REA, and WPA, plus Boulder/Hoover Dam

- The expansion of a continental airport system

- The GI Bill

- The Interstate Highway system

- Washington, D.C.’s Metro and San Francisco’s BART

Details on some of these in the first post in the series.