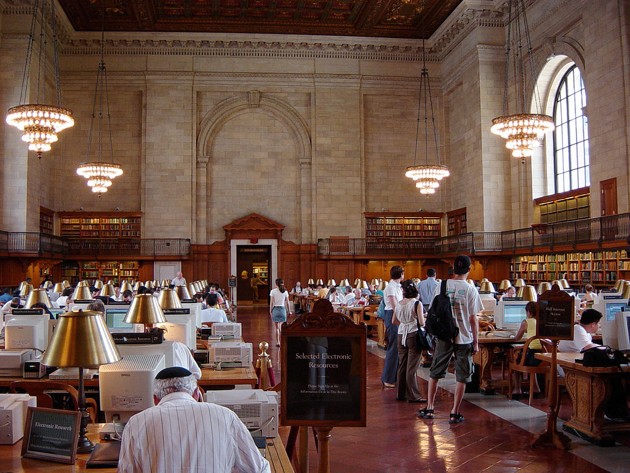

“This is our moment!” said Tony Marx, the President and CEO of the New York Public Library (NYPL), as he was winding his comments about the present and future of libraries up to a crescendo: “Libraries are the central institution of civil society with the largest reach for everyone.” He continued with his carpe diem challenge that now is the time to work in a bigger way than ever before to scale up his library’s reach and to both preserve its long-held traditions and transform its offerings to suit the 21st century.

The NYPL, like many other libraries around the country, has already begun to seize the day in an effort to answer the needs and wants of its community.

Marx listed a number of the efforts underway in the NYPL system: free classes for English as a foreign language and citizenship preparation, after-school (10,000 strong) and pre-school programs, basic computer skills and even coding instruction, and a program to lend 10,000 wifi hotspot modems to New Yorkers needing internet access. He described a dream to build a two-block long educational space to showcase some of the library’s unique treasures (long stored in protected vaults) so school kids can come to see an original copy of the Bill of Rights, a copy of the Declaration of Independence with Jefferson’s own handwritten edits, and a letter from Christopher Columbus to King Ferdinand declaring, as Marx paraphrased, “I think I found something.”

New York has the largest public library system in the world with over 90 locations. In poorer neighborhoods, Marx said, the library is the place for people to go, where people find essentials that may be missing at home: quiet, air conditioning, books, and computer access. Part of his mission is to bring those branch libraries “up to snuff,” as he puts it.

Marx talked about visiting a library in the South Bronx and finding a young boy sitting outside on the library steps, after hours, doing homework on his aged laptop because it was the only place where he could get internet access. “Holy Moly,” he said with incredulity, citing as well the fact that there are close to 3 million New Yorkers who can’t afford internet service.

I wrote about a similar story from Charleston, West Virginia, here:

…Some 41 percent of West Virginia households do not have broadband internet connections (trailed by New Mexico and Mississippi). Furthermore, more Internet users without computers at home report going to the public libraries for access than anyplace else.

If you need more convincing that these services are necessary, listen to this human story: One early morning before the library opened, a man was spotted settled in outside over behind the dumpsters—the dumpsters!—working on his laptop. He had found a strong library wifi signal right there, and was getting some work done while the library was still closed.

And Marx could probably have added other stories, like the one I heard in Columbus, Ohio, about library services for job-seekers:

Education efforts in Columbus libraries are a continuum from the kids on through “life skills” for adults. This means adult literacy programs, career and technology literacy, and financial literacy. Here is a true story that gives a sense of the realities: A young man comes into the library seeking help with a job search and filing his application for work. A librarian helps him load the application onto the screen. They agree he’ll fill it out and she’ll return to look it over. The librarian returns to discover the man has completed the application, not by keying in the responses, but with a marking pen on the screen.

The successful libraries I’ve seen on our American Futures adventure, in tiny towns like Winters, California, and Columbus, Mississippi, or medium-sized ones like Redlands, California, and Bend, Oregon, or larger cities like Columbus, Ohio, all share at least one trait: a deep, keen sense of the communities they serve. Here are some examples of how libraries are already seizing the moment to change:

In Winters, the Friends of the Library scout the town parks for new moms pushing strollers, and present them with a baby box including bibs, books (in a choice of Spanish or English), and an application for a library card. In Columbus, Ohio, library staff hit the laundromats, churches, shelters, and shops looking for moms with preschool-age children to entice to the library.

Preserving Traditions

In Columbus, Mississippi, the library holds the archives of handwritten journals chronicling Civil War battles and slave sales and purchases. In tiny Eastport, Maine, there is a special display featuring a newly-completed 1200-page dictionary of nearby Native American Indian language, Passamaquoddy-Maliseet.

Transforming the Mission

In Columbus, Ohio, the new spaces in the libraries provide quiet, comfortable reading space for older “guests,” as they are called, as well as tech-enabled classroom space, and bright, colorful pre-school areas. In Redlands, California, there are story hours in Mandarin. In Fayetteville, New York, there are maker-spaces. In libraries all over, there are young entrepreneurs who are making the library their start-up business office. In Duluth, Minnesota, there is a seed lending project within the library for the busy community of gardening enthusiasts.

The lists go on and on.

For Marx, it is about making libraries the vehicle for delivering an equality of opportunity. He says, speaking to his Aspen audience, that he wants “a world in which opportunities we all have in Aspen, at home, are shared by everyone—access to ideas and information, not constrained by economic ability or physical proximity. I want everyone in the game.”