Our reporting colleague John Tierney has prepared a brief introductory videoto help launch our new season. There’s no sound (tranquil!) but lots of pictures. It describes what we’re doing with this reporting series. I invite you to take two or three minutes to look at it (YouTube version here), then I’ll preview some of the themes and topics we’re going to explore through this coming week, in Fresno, California.

Welcome back from the video. Now it’s time for two maps, and a couple of photos, that set the stage for our reports about Fresno.

Fresno is the biggest city in California’s Central Valley, which is simultaneously one of America’s richest and poorest areas.

It is poor in the usual sense: by far the highest unemployment rates in the state, lowest median incomes, highest rates of poverty, worst remaining consequences of the financial crash of 2008, most serious pollution and public-health challenges. By many calculations, if California were indeed broken into six states, as the venture capitalist Tim Draper has proposed (hint: this won’t happen), the resulting state of Central California would be the poorest in the country.

Fresno shares its region’s strengths, as an agricultural center, and its challenges, of poverty and pollution. It also shares a trait with other places where we’ve spent time, notably the Golden Triangle of Mississippi (as explained via Joe Max Higgins here and the Mississippi School of Math and Science here) or much of the state of West Virginia (as explained by Larry Groce)—or parts of South Dakota or South Carolina or Georgia or rural Maine or the Rustbelt generally.

That trait is an acute awareness of being looked down on or condescended to by big-city fashionable America. I feel entitled to say that, both because it’s true and because I grew up in, and still think of myself as being “from,” a place in the same situation: the unloved “Inland Empire” of semi-desert Southern California. (The locus classicus of my home town as loser-land is of course Joan Didion’s “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” which came out when I was in high school.) That awareness—the realization of connoting the opposite of “the Bay Area” or “Cambridge” or “Westside LA”—plays a part in the drama of these areas, and, as we’ll show, in their efforts at turnaround.

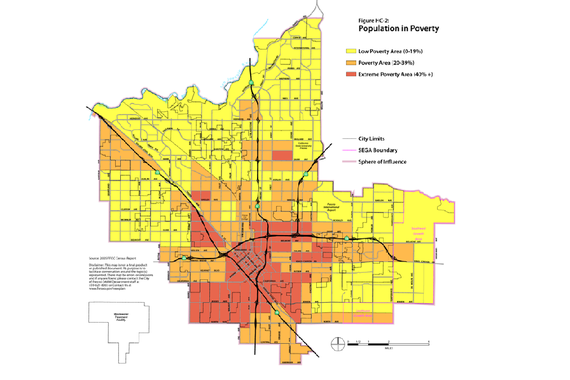

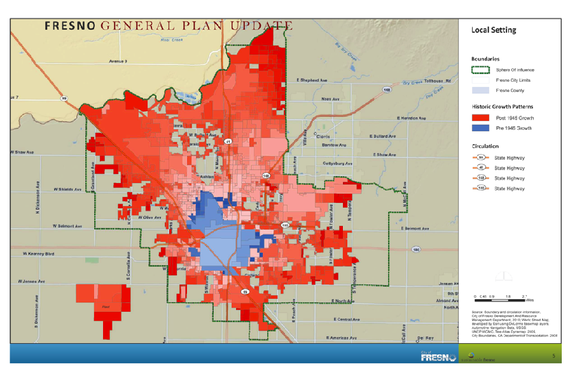

Now the two maps that set up the story of Fresno. I’m not counting the “six Californias” map, since that’s imaginary. The two below, which we saw in the office of Fresno’s popular Republican mayor, Ashley Swearingen.

The first is where Fresno’s richer people, and its many very poor people, live. The triangular area near the bottom, where the shading is darkest and where 40 percent or more of the people are impoverished, is where all the buildings of the historic downtown are located.

The second is where the city has grown in the 70 years since the end of World War II. The blue area shows the city’s concentrated downtown growth through the end of World War II. The red is where development—mainly suburban sprawl and malls—has happened since then.

“Fresno is famous as a victim of sprawl … ” I said last week when beginning a question to Mayor Swearingen; in her six years in office, she has been a big booster of downtown renewal efforts. “I’m not sure I’d use the word victim,” she broke in to say. “We were the perpetrators!” She was referring to a build-toward-the-horizon policy through much of the postwar era.

Another view, during what should be prime shopping hours.

This looks, and seems, pretty bleak. And that is why the people and groups we’ll be chronicling in coming days were both surprising and impressive in their determination that downtown Fresno would be the place where they would start their companies, realize their ambitions, and help rebuild a community. This is the hardest-hit area in a hard-pressed town in a region the rest of the state relies on but generally ignores. (For instance: The opening leg of California’s much-discussed High Speed Railroad, which will begin in Fresno, is referred to in coastal California as “the train to nowhere.”)

The next installment will begin with a look at Bitwise Industries, which advertises itself as the Mothership of Technology in the Fresno area — and which, over the past year in which we’ve been following it, has done a lot to back up that claim.

One of Bitwise’s graphics for its Fresno Tech revolution

One of Bitwise’s founders, Jake Soberal (the other was Irma Ogluin) grew up in nearby Clovis, went East for college, worked as a big-city lawyer—and then decided to come back and try to be part of an entrepreneurial revival in Fresno. He told a local business magazine that when he gave a commencement address at Clovis High, “I can distinctly remember sitting up there, this arrogant 18-year-old thinking, you know, these folks really ought to enjoy this speech because they’ll never see me here again.” He told us recently, “Solving problems in any place is valiant, but if you can solve them in Fresno, you can solve them anywhere.” As we’ll explain, he’s now part of a combined effort to develop Fresno’s own technology businesses, and crucially also to train its community-college, non-college, and non-high-school-degree populations with better opportunities in the tech world. “If this project can work right here, in the middle of a lot of the biggest challenges facing American cities, what might it do elsewhere?”

Local boosterism is a familiar part of the American fabric, from the days of Mark Twain or Babbitt to Waiting for Guffman and beyond. But we think this is something different—more than just faith, as in the Fulton Street mall show below— and we’ll explain why in days to come.