n the March cover story of The Atlantic, How America Is Putting Itself Back Together, my husband, Jim Fallows, also included a sidebar called “Eleven Signs a City Will Succeed.” He describes traits we found in towns that were doing very well. A lot of towns have written in to us after a look in their mirrors; some were quite self-satisfied, others showed angst. You can read about towns from Dayton to Bloomington to Detroit here and here.

We returned to Greenville, South Carolina, a few weeks ago—a town we first visited more than two years ago, and one of our favorites. I was curious to see how Greenville would stack up against the list. As an outsider, you can easily check off some of the obvious items on the list, like the presence of a community college, a revitalized main street, public-private partnerships, or unusual schools. But it is harder to get a sense of one of the softer items on the list:

#4 People know the Civic Story: Do people have a sense of how today’s efforts are connected to what happened yesterday and what they hope for tomorrow?

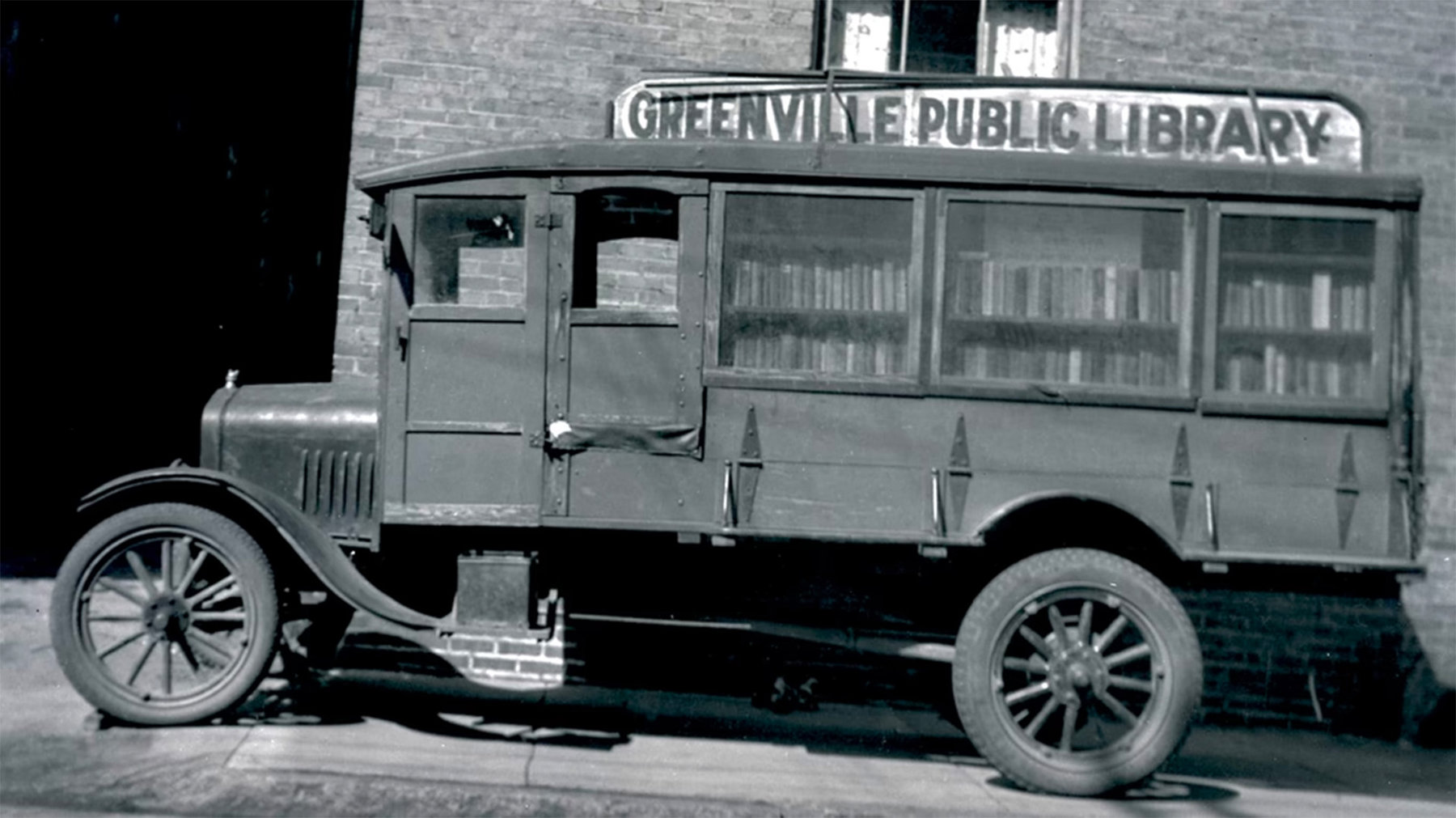

So, on a blustery morning, windy enough to blow my umbrella inside-out several times, I headed for Greenville’s public library. A town’s library, I have learned from our travels, can be a pretty good place to look for clues to the civic narrative of a town.

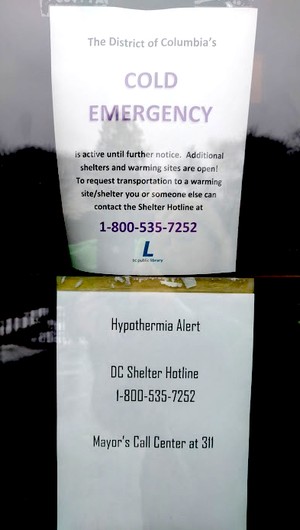

Libraries can serve as public stewards of the history of a town, for example, with their archives of newspapers and photographs, often on display. They speak to the current wants of a town with their programming and to the needs of a town by attention to its problems. (During this cold winter, our neighborhood library in Washington, D.C., posted a sign directing homeless where to seek emergency shelter when the library was closed.) And libraries can offer a reflection of where a town is heading with their own plans.

And along my route to the library, about a mile’s walk from the downtown hotel where we were staying, I was on the lookout for signals of Jim’s favorite sign:

#11. They have craft breweries.

Ok, I agree, breweries are a sure sign of improving lifestyle, but they’re at #11 as a proxy for numerous other things of entrepreneurial and youthful spirit, like an attractive river walk, a local coffee shop, an outdoor market, or good, public, recreational facilities.

Immediately, I was off to a good start. I took the steps, a pedestrian shortcut, from our hotel down to the Swamp Rabbit Trail, a county-broad greenway system for bikers and walkers along the Reedy River.

Turning west, there was a small collection of artist studios, and a bronze statue to one of the founding fathers of the town—one of a series of several I had seen around town.

I glanced back across the river where the shell of an abandoned factory paint shop was transformed into an elegant public-event space.

I passed the busy construction of one of Greenville’s new hotels and a downtown apartment residence. Crossing the river and turning uphill, I quickly lost count of the number of churches I had passed. I knew churches play a big role in Greenville; many people told me that the first question you ask in Greenville to get a sense of a new acquaintance is not “Where do you work,” or “Where do you live,” but “Where do you go to church?”

Up the hill, in front of the public-transit center was a bike-share station and a bike-repair station, with a screwdriver, Allen keys, wrenches, and a tire pump. There are also some with futuristic plastic pods that are actually rentable, protected bike lockers.

Two more blocks to Heritage Green, once the site of the Greenville Woman’s College, originally named in 1854 as the Grenville Baptist Female College, and now a campus of several of Greenville’s finest educational and cultural institutions: the main public library, four separate museums, and a theater.

***

It was nearly March, and the bright warm spaces of the library were welcoming everyone from the town professionals to researchers to the homeless. It was almost the start of the Upstate’s month-long celebration of its international heritage. The North American headquarters of Michelin, the French tire company, is in Greenville, along with an R&D center, a sales and marketing training center, and a car-tire manufacturing plant.

Michelin was sponsoring the so-called InTIREnational Art Contest. Each entry uses scrap Michelin tires to create an internationally-themed design. The two winners would take home $5,000 each.

Beverly James, the executive director at the Hughes Main Library, toured me around and told me about some of the other collaborations that the library enjoyed. The Greenville Symphony Orchestra performs short pieces for pint-size audiences in a BMW-sponsored series called “Lollipops” for kids and families.

The Greenville International Ballet brings dramatizations of children’s books with ballet themes to the library.

Their longest collaboration, James told me, started in 1999 with the Chautauqua Institute family. In Greenville every summer, Chautauqua in Greenville presents a historical interactive theater, and the library works with them on supportive programming throughout the year.

The children’s area of public libraries is invariably one of the favorites. Greenville, like many other libraries, is dedicated to their early-literacy program. In Greenville, they go well beyond the familiar story hours for toddlers. They trained their staff in a program called Mother Goose on the Loose, designed for 0-to-3-year-olds and their caregivers, who learn how to replicate what they’ve done at the library at home. James told me that part of the whole pre-literacy process she addresses is helping parents understand that getting every child ready to read does not mean teaching them to read. Ready is the key word here.

In many libraries, from Duluth to Columbus, Mississippi, to San Bernardino and now Greenville, I’ve seen collections dedicated to the region. Redlands, California is in the process of building an entire museum of Redlands history, which will be administered the A.K. Smiley Public Library. Many librarians tell me that genealogy research is one of the most popular uses of the regional rooms. In Greenville, the photo archives, with civil war letters, textile mills, military camps—all digitized here—were amazing.

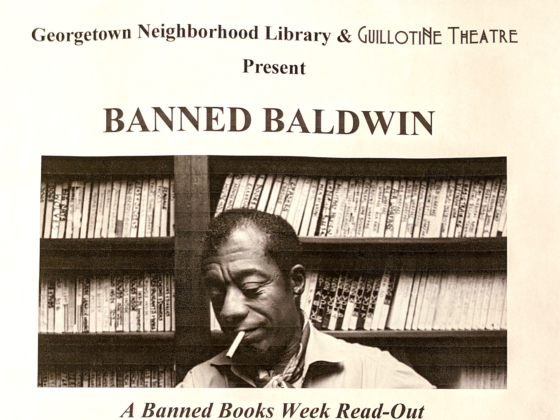

Just outside the South Carolina room was a display of photographs labeled “Civil Rights era Greenville,” including photos of the young Jesse Jackson, who was born, raised, and educated through high school in Greenville. During his first Christmas holiday home from the University of Illinois in the winter of 1959, Jackson tried and failed to find the books he needed at the Negro library. Getting them transferred there from the white library would take too long. As far as their holdings and their budgets, the libraries were “separate, but not equal,” Beverly James told me. Jackson went to the white library, where he was refused the books.

The next summer, Jackson returned to Greenville. He and seven other young Greenville Blacks marched to the white library, entered, refused to leave, were arrested, and spent about 45 minutes in the city jail. A few weeks later, an African American attorney in town filed suit to integrate the public libraries. On September 2, 1960, the libraries were closed in face of the lawsuit. Then, the judge dismissed the case because the closed libraries were ruled “nonexistent.” The libraries reopened, integrated, on September 19, 1960.

Barely trying, I stumbled on many hits for Greenville’s #4 civic narrative and #11 craft brewery proxies, from the American Futures’ “Eleven Signs a City Will Succeed.”