I’ve been warming up to do a big report on what is interesting, and uncertain, about the big push underway in Fresno to rebuild and revitalize what is now its very troubled downtown. Then I realized that instead of trying to swaddle the whole thing in narrative, it would make most sense just to deliver the main points. That’s what you’ll find below.

Now, back to Fresno, an hour’s drive north of McFarland on Highway 99.

Yes, you can find exceptions. But most of the time, when you’ve got a downtown district with a self-sustaining combination of retail outlets (especially non-chain stores); restaurants and bars and brewpubs and music sites (to draw people downtown at night); public art or festivals or live events (to give people a civic sense-of-self); and, crucially, residential spaces (where people who don’t have children or whose children have grown up live in second- and third-story apartments above stores and restaurants, providing street life through the evening and a general sense of bustle in downtown)—when find a place with those things, it’s very likely that all the other economic, cultural, civic, and educational indicators of local well-being will be positive too.

• Stages of downtown recovery. But a successful downtown is not all-or-nothing proposition. We’ve seen cities at almost every imaginable point along this curve. Full, functioning ripeness—as in Greenville, South Carolina; Burlington, Vermont; Columbus, Ohio; little Holland, Michigan; or Riverside, California. Nearly there—as with Sioux Falls, South Dakota, or Winters, California. Moving in the right direction—like Duluth, Minnesota, or Columbus, Mississippi, or Redlands, California, or tiny Eastport, Maine. Just kicking off a big new effort—as in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Or trying to figure out what to do next—as in San Bernardino, California.

Along this arc Fresno occupies an interesting position. To outsiders, it looks as if the downtown is still in quite tough shape. To the people working on its recovery, the big, important decisions about moving forward have been taken, and the payoff is about to appear. As suggested by the ubiquitous stickers for the downtown “I Believe” campaign. By the way, the I Believe Fresno site has a useful interactive timeline to illustrate the rise, fall, and hoped-for rise-again of the downtown district.

• Background source of trouble. In a few cities, the main problem has been fundamental economic dislocation. In Ajo, Arizona, as we’ll soon describe, a giant copper mine closed, suddenly eliminating most of the area’s job. Similar pressures have affected Charleston, West Virginia, as the coal and chemical industries contracted, and Pittsburgh long ago (before its rebound) as the steel factories went down.

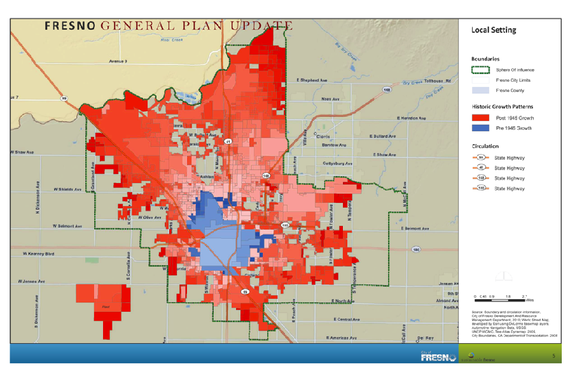

But in many other cities, the problem is: sprawl, sprawl, sprawl. As I mentioned last week in kicking off the Fresno coverage, the city is kind of laboratory study of the destructive power of sprawl. All of the tract-home development and malls went to the north side of town, and the poor people and the blood banks and the payday check-cashing operations were concentrated in what was once the downtown commercial center. Here again is the useful map that we saw in Mayor Ashley Swearingen’s office of where the city grew before World War II, in blue, and where it grew after that, in red.

The blue area is full of once-grand, now mainly run-down commercial and civic buildings, plus the city’s poorest residents. The red is familiar mall-and-tract-home territory and economically better off.

That’s been the case in Burlington, Vermont, from the then-Socialist mayor Bernie Sanders through the current Democratic mayor Miro Weinberger. It’s been true in Greenville, South Carolina, from the Democratic mayor Max Heller through the current Republican Knox White. (I compared-and-contrasted Burlington and Greenville in this magazine article.) It’s been true in Duluth, Minnesota, from Gary Doty to current mayor Don Ness, both from the Democratic-Farm-Labor party. Or in Columbus, Ohio, especially under current Democratic mayor Michael Coleman. And in cities with weak-mayor systems, you will find some other strong figures in public-office positions: county commissioners, hired managers, etc.

In Fresno, the public champion and exerciser of public leverage through the past six years has been Ashley Swearengin, a Republican who was elected six years ago, at age 36, and got 75 percent of the vote in her re-election run two years ago. (She is term-limited and has only two more years to go. Whatever their pluses or minuses elsewhere, term limits seem an obviously terrible idea for most city governments, since steering a city’s development is best done over much longer time horizons. That is, voters should have the option to keep mayors in place if they want.)

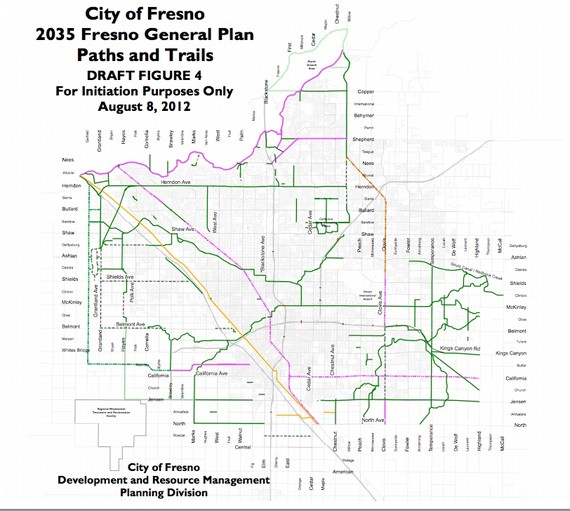

When we visited Mayor Swearengin in her office, she spent all her time pointing from one map to the next, showing the sequence in which changes in traffic flow, public-transit lines, development hubs, and so on, could help the city recover. She told us that the blue/red map you see above, combined with another one showing the concentration of poverty downtown, “is what caused me to run in 2008.” She pointed to another map for the city’s 2035 General Plan (which you can see here), with more or less the view you see in the next image, and said, “Here you see the downtown as the city’s heart, and Blackstone [a main N-S drag] as the spine, residential areas as the lungs…” and on through the parks and trails and transit lines that “would give life to the city.

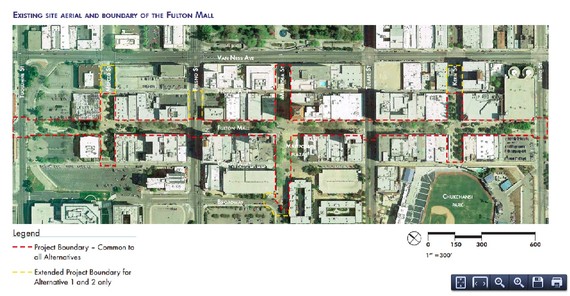

An an aerial view, in her office, of the city’s now sclerotic heart:

The details of the downtown redevelopment plan are voluminous—and, to me, very interesting, but I’ll skip past them today. I will say that you can find an overview on the city’s site here, and if you’d like a nearly 400-page chapter-and-verse you can find it in a PDF here. The point for now is that successful cities all seem to have a public figure who invests a lot of capital in downtown improvement, and under Mayor Swearengin, Fresno has fit that pattern. Here’s one more of her 2035-plan maps, of the planned bike, walking, and running paths:

I’ve gotten this far in the post and this late in the day, and still have three list-points to make:

• The need for a shared city narrative, which is especially important in a city conscious of its many problems, as Fresno is. And,

• The ability to leap ahead in time, at least when it comes to thinking.

There’s more to say on each of those points, but since I’m hard up against a 12-hour period offline I will save them for the next installment. For now I will give a teaser from the final point. This is based on my talk with Jake Soberal, co-founder of Bitwise, whom I mentioned this earlier dispatch and whose company is opening a big, new downtown facility.

Where is Fresno on the arc of recovery? I asked him. “I drive down Van Ness [a main downtown street] to work each day. And if you’re a person from outside you probably think, ‘Well, you’ve got some historic buildings here. But it’s a pretty crummy downtown, compared to what’s happening in other places in America.'” I told him that is pretty much what I thought.

“But when I drive down that street,” he said, “I realize that Joe is doing a project there, and someone is doing a project there, and this building is under lease, and that building is about to be reopened. And I look at it and think, It’s done!”

“I mean this earnestly, and I’m not being flippant. Downtown revitalization in Fresno is done, in terms of making the decisions. Now we just have to let it happen.”

With allowances for the upbeat bias of any entrepreneur, I understood what he meant. More on what that means, and on the importance of private pioneers and a changed city narrative, in the next update.