The man you see above is Joe Max Higgins Jr, who is now in his mid-50s. He grew up in Arkansas as the son of a sheriff, and since the mid-2000s he has worked on economic-development programs for the part of Mississippi known as the “Golden Triangle.” You’ll see more about him and his colleagues here in coming days, and he will be part of a Marketplace radio segment next week. In this first installment I’d like to explain why I’m concentrating on him, and the larger trends he illustrates.

Through most of my life as a writer and as a person, the big issue for me has been “the American question.” That is: Is the country making it? How do its realities compare with its ambitions? Where has it set the balance between the creative chaos that is its secret, and just chaos? On the long arc of renewal and dissolution, where does it stand now? Most of my books have directly or indirectly addressed this theme.

The Great Man/Woman theory of events (Lincoln and FDR to the good, Hitler to the bad); the institutionalist emphasis (post-war Japan’s recovery to the good, institutional U.S. racism to the bad); environmental constraints or destruction (Jared Diamond about the past, who knows about the future); the tyranny or blessing of geography (China vs. the US); blunder or happenstance—these and other factors are usually all part of the story, and rarely the whole thing.

Let’s bring this back to earth. To avoid paralysis, you have to choose something to concentrate on, while remembering that inevitably more is going on. You do your best, which is how we came across Joe Max Higgins.

Here is the question about this part of Mississippi: Why is industry coming back?

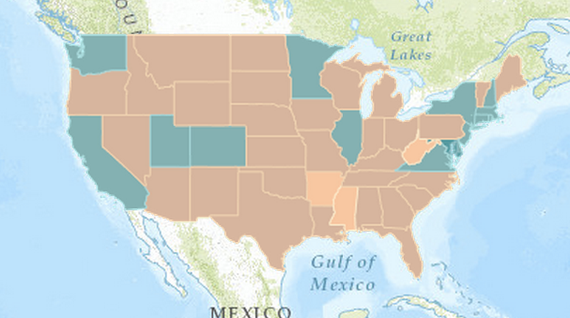

The map above, via Esri, shows median household income by state. The bluer the state, the richer; the tan ones are poorer. Mississippi is dead last of the 50 states, with a median household income of a little over $37,000 per year, versus just over $50,000 for the country as a whole and $64,000 for Connecticut.

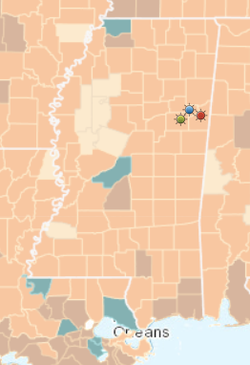

Above is a closer look at the state itself. In two areas—around Jackson, in the center of the state, and in the Memphis suburbs to the north—the median income is above the national median. All the rest are below. The lightest areas on the map are the poorest parts of the state, in the Delta. For instance, the median household income of Rosedale, Mississippi, on the river, is listed as $14,000. The three colored dots in east-central Mississippi represent the three cities of the so-called Golden Triangle: Columbus, in red; West Point, in blue; and Starkville, in green.

The three cities have different stories and situations. Starkville is home of the leading research university in the area, Mississippi State, and has the greater stability and higher-end amenities that come with being a university town. West Point is the smallest of the three and, in recent years, the hardest hit by economic change. In 2007, Sara Lee closed a nearly century-old meat processing plant that had employed more than 1,000 workers, fully a tenth of the town’s population. Since then its unemployment rate has been near 20 percent. Columbus was historically the richest of the three, but one also hit by the one-after-another collapse of low-wage manufacturing jobs that had come there through the mid-20th century. It has relied very heavily on the nearby Columbus Air Force Base, which Mississippi’s powerful Congressional delegation has defended through wave after wave of base-closing measures.

If you look away from the factories that have closed in the vicinity, and the downtown storefronts that are vacant, what you also notice are huge new factories opening up, as previously mentioned here. What you see below is a 1970s-era “Golden Triangle” airport built at a centerpoint of the three cities, and with Delta connections to Atlanta. Just beyond it is a sprawling, modern steel mill owned by the Russian Severstal company, whose scale is barely imaginable from this picture. Nearby are large factories making truck engines, helicopters, drones and other advanced devices, at wages equal to several multiples of the local household income. Not far away, Yokohama Tires of Japan is building a major new plant.

In all, the Golden Triangle region has brought in some $6 billion in capital investment over the past decade, creating some 6,000 new jobs, in a concentrated, poor region where this influx has made an enormous difference.

So here’s the question we’ll try to wrestle with. Why so much? Why here? And to what effect?

As suits the complexity of life, the answers go in every direction. The search for non-union labor is a central factor. Incentives from the state and local governments are another. Plain old political log-rolling has been crucial to Mississippi and some other Southern states: its representatives are tough on federal spending, and even tougher about keeping earmarked projects coming here. And on down the long list.

But there are countless places that offer incentives, and discourage unions, and would love to have the factories. Each of the big employers that has recently chosen the Golden Triangle considered scores or hundreds of other possibilities, many in the South and some in Mexico or the Caribbean, before coming here. Why here?

Allowing for all the other explanations, I will argue that in this part of the country, a handful of forceful people made the difference in shaping the region’s economy as a whole. In a way this is consistent with what we’ve seen in a number of other communities. A stalwart group is determined to give Eastport, Maine, a chance; a series of civic leaders shifted the Greenville area of South Carolina to a new civic and economic footing; successful business people who retained a strong local identity have made a huge difference in the character of Holland, Michigan, and Redlands, California.

In this part of Mississippi, it is harder to identify purely civic leaders who have played a comparable role. But it is hard to ignore the difference that the area’s economic-development team has made, including Joe Max Higgins and Brenda Lathan and their colleagues at a regional organization called the LINK, Raj Shaunak of Eastern Mississippi Community College, and others we will describe.

During that visit, my wife and I sat with Higgins in his office and asked him to describe the sequence of development in the area. What was the turning point. He had a long list, but he focused on “Eurocopter”— the facility, now part of Airbus, that makes helicopters for both civilian and US-military use.

“Eurocopter was really, really, a big deal,” he said. “It was important because they make helicopters! In a county and a state where most people think the women are all barefoot and pregnant, all the men got snuff up in their lip, we’re all members of the Klan—now we’re making something that flies! That genuinely changed our psyche. It was monumental. When Eurocopter came in, people started walking upright a little bit.”

It’s a story he had told before, and he reveled in the “barefoot and pregnant” effect. But he was talking about something real, as we’ll try in the next installments to explain.