To the north, the first traffic light is 144 miles away.

To the south, the first traffic light is 92 miles away.

There are no traffic lights here in Chester, Montana.

This is how the musician Philip Aaberg introduced his hometown of Chester, Montana, in a short radio commentary he produced for KCRW a while back, along with his wife, Patty, and their son Jake.

A privilege of our American Futures journey is that, occasionally, we can fly our small propeller plane far, far away to places like Chester, Montana. Chester lies at the top of the country, 30 miles as the crow flies from the Canadian border. From even farther west, we flew over the Bitterroot Mountains, which then rolled away into the high plains, with fields of green, yellow, and gold. The rivers below us meandered. The rail tracks looked very important. The roads indeed didn’t need traffic lights. In the skies, there was not another plane in sight for hours.

We had just spent some time along the Washington-Idaho border, to see one of the newly-finished Maya Lin installations for the Confluence Project, along the path of Lewis and Clark’s expedition some 200 years earlier than ours. And we were heading to the American Prairie Reserve in Northeastern Montana, to see the new rewilding of the American prairie with native bison, pronghorn antelope, and other animals. Chester was more or less on our way.

Our friends Phil and Patty Aaberg live in Chester. Phil is a musician—a pianist and composer with a collection of awards, performances, and collaborations that more than prove his bona fides to anyone who hasn’t had the good fortune yet to hear his music. Windham Hill Records, nominations for Grammies and an Emmy, and some 20 albums with names like From the Ground Up and Live from Montana.

After time on the east and west coasts, Phil and Patty moved to Chester, a town of about 1,000 people, to the house where Aaberg grew up, right across from his old school. Partly, they were looking for such a place to raise their young son (the older three were grown by then) and partly because, well, Montana always had a strong pull on Phil.

Back in the late 19th century, Chester was a stop for the steam engines of Great Northern Railroad to replenish coal and water. Homesteaders soon followed. Phil’s family has been there about a century. Already a serious music student as a young teenager, Phil would ride the train every few weeks to meet with his piano teacher in Spokane, a seven hour trip, or 10 if there were lots of stops.

When the Aabergs opened their Great Northern B&B, where we stayed with them, it doubled the number of lodging options for visitors and those just passing through. And then they opened another on First Street. Sometimes, people biking through the north will stop in Chester. Once, a biker stopped for a day, and ended up staying for a week, waiting to take delivery of some bike parts. It was one of those stories that you could imagine ending with something like, “And then he met my second cousin who runs the pharmacy, they fell in love, and he’s been here ever since.” That didn’t happen, but it was easy to believe it could have. Chester is that kind of town.

We flew into Chester’s tiny airport. It wasn’t unusual to find an airport there; some 5,000 small airports dot the country, a legacy of airstrips built for military pilot training around World War II, and then for civic and post office growth. Chester’s airport was even more convenient than most. When Phil heard our plane overhead, he could hop in his car with Jake, head the few blocks to the edge of town where the airport lay, and still have plenty of time left over to wait and see us land.

People who are from towns this small, this remote, and this beautiful grow up with a deep imprint of place on their lives, and for artists like Phil, on their work. I know this firsthand from my childhood in a small town on the shores of Lake Erie.

In a formal interview he once gave, Aaberg talked about how this place—these northern plains and his hometown—has inspired the music he creates.

Sounds from Montana

Aaberg describes the early days of noticing music, when his mother and grandmother were choir directors at the Catholic Church. He heard a lot of music, including Gregorian chants. He recounts the first time, at 4 years old, when he ran home from church to the family piano to sound out a tune he had heard. He described the thrill of figuring that out all by himself, and recalling it vividly as the moment that he knew what he wanted to do for the rest of his life.

When Aaberg is touring on the road, he builds in time to teach a little music to the schoolkids in the towns. He includes listening exercises, having the kids pause to just listen to the sounds around them for a whole minute. “Listening is the most important thing you can do,” he tells them. “If people in the world would listen to each other, the world would be a lot safer place.”

Time in Montana

Aaberg says, “I love this land. There is something about this country that really opens me up.” He talks about the amount of time and the quality of the time he spent in Chester. “When I was here, I was really here.” He talked about the relationship between his music and seeing the land here, watching the sky change, seeing the Sweetgrass Hills, watching the flights of birds. “All incredibly important to me,” he says, and a source of his inspiration.

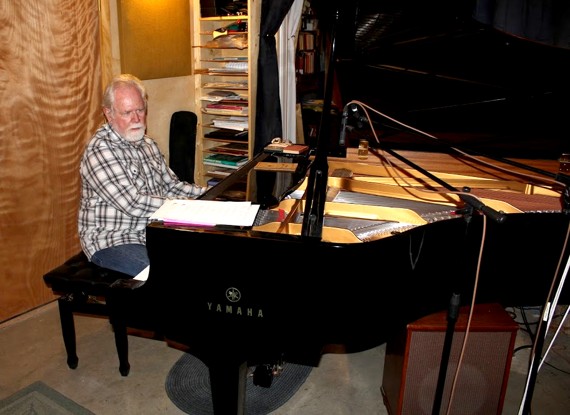

Phil built his studio, fittingly, from an old grain silo. He invited us in to look and listen a little while. He played some of the songs I knew; now that I had been in Montana, I recognized that they actually sound like Montana.

After we headed east to the American Prairie Reserve, I got an email from Phil. He said he was heading out to go camping in the Sweetgrass Hills. Lucky man. You can’t get to Chester, Montana, today, or probably even tomorrow. But you can bring a bit of Montana into your life through this music. You can listen hereand here and here, and find more music here.