I was standing at the front desk of Charleston, West Virginia’s main library on Election Day 2014 when a burly man in worker’s clothes stopped by just to announce to the librarian, “I voted yes on the levy!”

It was an important day for the libraries of Kanawha County (pronounced kuh-NAW in Charleston). Passing the levy would mean almost $3 million a year for the next five years, which amounts to about 40 percent of the libraries’ budget for operations and staff. Losing the levy would mean—well, no one even wanted to contemplate that.

I went to the library to talk with the library director, Alan Engelbert, and Cheryl Crigger Morgan, the president of the library board, about the library, the vote, and the consequences, no matter which way it turned out.

The history of the library funding that took them to the 2014 election day levy is convoluted, but here is the very short version (If you want a fuller version, click here, here, here, and here): In an unusual arrangement, the Board of Education began funding the Kanawha County Public Library system in 1911. In 1957, a new statute rearranged that obligation, and the Board of Education funding was cut from the full 100 percent to 40 percent, with the rest coming from the Kanawha County Commission (40 percent) and the city of Charleston (20 percent). Additional grant and aid money comes from the state and privately raised funds from the Library Foundation, including its Friends of the Library committee, and other sources.

In 2013, the West Virginia Supreme Court ruled that the Board of Education was no longer obligated to fund the libraries. Later in 2013, the Board agreed to host a levy that would include one-eighth of the total, or $3 million for the libraries. The levy failed, undoubtedly in part because of the ironic twist that the acting school board president campaigned against the levy, saying people were taxed too much as is.

The results of these losses have been severe. Engelbert said that keeping up the strong tradition of services has been the primary goal during these lean times, but it has meant big challenges for a barebones staff, which is shaved down to 42 from a former 160 positions. “If somebody catches a cold,” says Englebert, “we have big problems.”

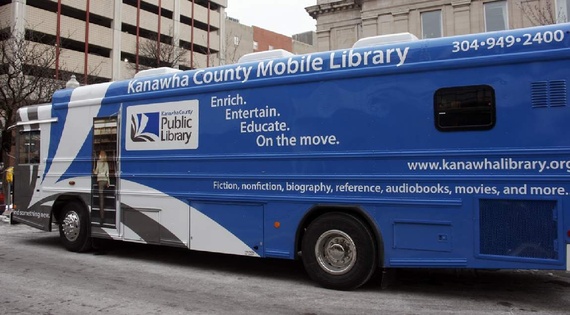

The reach and workload of the library is vast; they serve a population of 192,000 residents in Kanawha County, including 127,000 library card holders. (Students are automatically issued library cards.) There are 10 branches of the library and a traveling bookmobile that serves rural areas.

The close, critical relationship between the libraries and the schools, which includes 46 school libraries, can be labor intensive. For example, teachers can request supplementary teaching materials like books, DVDs, and other extras for lessons and projects, which librarians assemble and pack up for deliveries to the schools. And last summer, the library ran a comprehensive Farm-to-Table program for 3,000 kids. You can see lots more of the library activities on their Facebook page.

The libraries are also a pillar of tech support for adults. A U.S. Department of Commerce commissioned report from 2013 demonstrates that West Virginians need that support. Some 35 percent of West Virginia households do not have a computer at home (trailed only by Mississippi). And some 41 percent of West Virginia households do not have broadband internet connections (trailed by New Mexico and Mississippi). Furthermore, more Internet users without computers at home report going to the public libraries for access than anyplace else.

If you need more convincing that these services are necessary, listen to this human story: One early morning before the library opened, a man was spotted settled in outside over behind the dumpsters—the dumpsters!—working on his laptop. He had found a strong library wifi signal right there, and was getting some work done while the library was still closed.

And there is more to do: Maintaining the holdings of the library, like data bases, magazines, music, foreign language learning programs, not to mention books—and staffing the ask-a-librarian general research help. Conducting classes, clubs, events, and demos of all sorts. The list is so long; you can find it on the newly-launched website.

Funding cuts also meant the library had to shut its doors on Sundays. It also meant discontinuing the popular West Virginia Book Festival, which packed 2,000 people in to the town’s new Civic Center in 2012, bringing authors, publishers, tourism, book sales, and a sense of pride to Charleston.

So here we are: November 2014. The Board of Education agreed to sponsor another levy, this time solely for the libraries. It offered a chance for revival. A “Vote Yes for Libraries” Committee formed to tackle the marketing campaign to educate the public about the levy (Board of Education sponsored, but library funding only), to dispel hearsay that the fund would be used for new buildings (an earlier effort that has been on ice for a long time) and to make clear that funds would be used for operations and staff.

They also faced another challenge, which all libraries today face: Bucking the old-fashioned, broad-brush perception that they are just about lending books, which can translate into a ballot-box reaction of “Why would the libraries need all that money anyway?” Introducing citizens to all that the libraries do and changing the sense that the library has become a “hub of the community” takes a lot of work.

In Charleston, the “Vote Yes for Libraries” public campaign has engaged: 40-to-50 volunteers, 75 speaking gigs all around the valley civic groups, 2000 yard signs, a website, T-shirts, honk-and-waves on election day morning, Halloween displays, and lots more.

When I was talking with Engelbert and Morgan on election morning, they were cautiously excited about what a victory could mean. Their wish-list would include: Beefing up the staff, opening more hours, gearing up the the book festival, and reinstating the tech support center, for starters. Beyond meeting daily needs, it would mean time to address all manners of library planning and scrutinizing new leadership roles, which obviously carry long-term effects for the future of the library.

I asked about the biggest dream the library would have. Engelbert answered without missing a beat: The zero-to-3 year olds. That, he said, is the really big one. Getting the littlest citizens ready for school, engaging their parents in the effort, is what the library wants and needs to be part of.

So, that is what the library levy means to Charleston. Fortunately, on November 4th, the levy passed—brilliantly—with a whopping two-thirds majority. More than 32,000 voters ticked Yes. Congratulations.