On April 16, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. penned his epic “Letter From Birmingham Jail.” He had been arrested on the Good Friday before, while taking part in a peaceful civil-rights protest. King sent a handwritten draft to The Atlantic, and it was published for the first time in the magazine—then called The Atlantic Monthly—in August of that year. In the letter, he wrote in part:

There are some instances when a law is just on its face and unjust in its application. For instance, I was arrested Friday on a charge of parading without a permit. Now, there is nothing wrong with an ordinance which requires a permit for a parade, but when the ordinance is used to preserve segregation and to deny citizens the First Amendment privilege of peaceful assembly and peaceful protest, then it becomes unjust.

Of course Jim and I had the letter on our minds when we visited Birmingham, Alabama, this fall. We thought about The Atlantic connection, but we also had another connection there: Jim had gotten his first job as a journalist in Montgomery, Alabama, reporting for the Southern Courier and frequently visiting Birmingham in the summer of 1968.

There have been a few times during our travels across the country for the American Futures project over the last three years when we have come face to face with references to powerful pieces that we knew resided in the bulky, delicately-aging bound volumes of The Atlantic, which sit in the magazine’s office in the Watergate building today.

One time was when we sought and found the now-abandoned homestead of Caroline Henderson, a young Mount Holyoke graduate who followed her dream to the Oklahoma panhandle in 1907 to farm. She did farm for 28 years, and but for the timing, Henderson would probably have continued to thrive. She survived the drought of the 1930s, although her greatest legacy was not a farm, but a series of evocative letters published in the magazine chronicling her ordeals called “Letters from the Dust Bowl.”

When we landed in Guymon, Oklahoma, in late fall of 2014, and went to look for Henderson’s homestead, we found her abandoned house, just as she described it, at the intersection of Roads N and 9, and we returned home with the treasure of a small batch of rusted, homemade six-inch nails, which we found near the remains of the chicken coop, and which we gave to today’s owner of The Atlantic.

* * *

On our third day in Birmingham, I visited the Central Library of the Birmingham Public Library system. I wandered aimlessly for a bit and found my way upstairs toward the children’s section. The young teen librarian, Lance Simpson, asked enthusiastically if he could help me. Help began with a tour through regular Wednesday after-school tech lab program for middle- and high-schoolers. On this day, they were working on graphic design with their volunteer teachers, who were students from University of Alabama at Birmingham. The endgame of this series of classes—after circuit-board soldering, computer-aided-design instruction, Arduino programming, 3-D printing, and more—was robots, always a favorite.

Simpson left me with Kar’yn Davis-West, the library’s public-service coordinator, who had just finished handing out cake for Friends of the Library’s Patron Appreciation Day. She toured me through the modern East Building of the library, describing some of the many programs and pointing out the various areas for computers, reading, the books, workspaces, the art gallery, etc. Then we walked across the overpass to the original neoclassical building, now called the Linn-Henley Research Library, built in 1927 after the town’s old quarters in City Hall burned.

The library wanted to make a statement to the town that they were there to stay, explained Davis-West, and they commissioned murals for the building from Ezra Winter, a renowned and accomplished artist who became a leading muralist in the country. His early years began in glory, with a three-year residency at the American Academy in Rome, not far from the Sistine Chapel, and ended tragically, when he fell from a high work scaffold, lost his ability to paint precisely, and ultimately took his own life. My favorite of his murals were for the children’s section. They represented major children’s literature from 16 countries around the work, and included images of Lancelot, Pocahontas, Krishna, Don Quixote, Goldilocks, Confucius, and many others. The library continued is tradition of murals with a 2003 Ronald Scott McDowell mural in the East Building called A New Day in Old Birmingham, celebrating the diversity of Birmingham’s population today.

Then we wound our way down to the archives. Mary Beth Newbill, the head of the Southern History and Government Documents Departments, showed us around. Holdings include the Tutwiler Collection of Southern life and culture and the Rucker Agee map collection, which serves as a history of cartography and southern U.S. geography with over 4,000 maps and atlases dating from the 16th century.

Newbill and Davis-West then carefully opened a giant white trunk, which looked hermetically sealed and as big as a small coffin, and undid from the protective layers of padding and wrap, a nearly three-foot-tall traditional Japanese doll. But not just any doll. Miss Iwate, named for Iwate Prefecture in northeastern Honshu Island in Japan, was sent to the children of Birmingham in 1928, as a thank-you for several dolls that the children of Birmingham had sent to the children of Iwate as part of a goodwill exchange of Friendship Dolls.

The exquisitely handcrafted Miss Iwate, with her silk kimonos, crushed-oyster-shell head, and real human hair, is one of 58 dolls sent to the United States. Miss Iwate made one return trip to Japan for a knee repair, and now she is perfect again. She comes out for display on special occasions. Only about a dozen of the Japanese dolls have gone missing. By contrast, only about 330 of the more than 12,000 American-made blue-eyed baby dolls survived World War II and still exist in Japan.

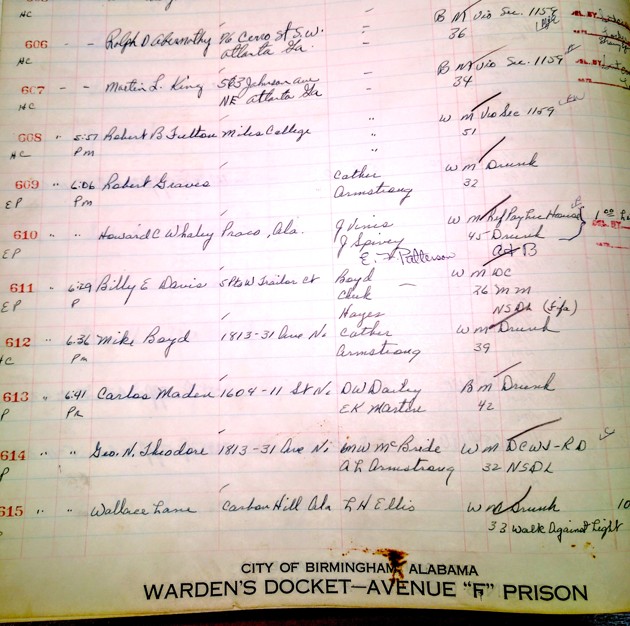

Then we went further into the archives, where the best was saved for last. Catherine Oseas, the assistant archivist, disappeared into a back room and emerged with a heavy ledger. It was a book of the warden’s admissions to the Birmingham Jail for 1963. Docket numbers 606 and 607, for April 12, are the names and addresses for Ralph D. Abernathy and Martin L. King, who were cited in violation of Section 1159 of the Birmingham Parade Ordinance. Docket number 561 was Fred L. Shuttlesworth. It was extraordinary to see these ordinary, humble pages—a reminder of the treasures guarded by our public libraries.