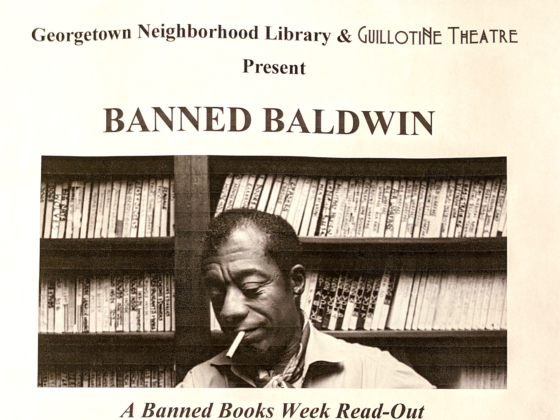

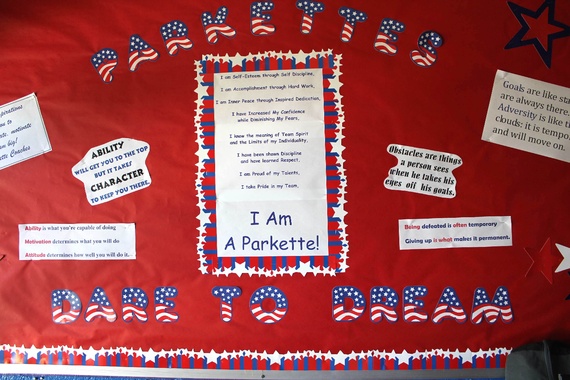

The Parkettes. It sounds like a ’60s girl band, but it’s not. If you’ve dipped into the world of gymnastics beyond watching the Olympics every four years, you probably already know that the Parkettes—the name applies to the team, the building, and the program—is a national training center for U.S. gymnasts in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

In many ways, the Parkettes is indeed a product of the ’60s, and the story of their origin is a heartwarming, classic American saga. Donna Strauss, who founded the club with her husband Bill, told me about its early days as we walked around the cavernous 35,000 square foot space that is its home. The floor was bustling with girls flying from one uneven bar to another, muscling through sets of pull-ups, pounding at top speed toward a leaping flip over the vault, and walking on their hands in rows, with precise upside-down posture across the floor. Doing anything they were doing looked impossibly, implausibly difficult.

In the 1960s, Donna and her husband Bill were teaching in the Allentown public schools. This was the pre-Title IX era, of course, and as a PE teacher, Donna was keenly aware that while the boys in Allentown had their football, basketball, and wrestling, the girls’ athletics were spare. So she decided to start a girls’ gymnastics program and asked the principal, a man named Carroll Parks, for help with space.

Principal Parks came through, daring to carve out floor time for them from the boys’ basketball practices, and then opening the gym doors on Saturdays to the girls as well. He was such a motivator for Strauss and the girls, said Donna, that they named the now-legendary Parkettes in his honor.

The early gymnasts practiced at school, at a church, in a barn, and in a neighborhood backyard. The high-school shop teacher built the girls their first set of uneven bars. The program grew and flourished during Allentown’s first glory days, when next-door powerhouse Bethlehem Steel was making jobs for the region and steel for the iconic structures of America—the Golden Gate Bridge, the Hoover Dam, and the Empire State Building, to name a few. The Mack Trucks headquarters and plants were right in town, as was the elegant, busy Hess’s department store, a regional attraction for the Lehigh Valley and beyond.

Allentown’s philanthropists were generous. In 1979, Donna approached Alfred Pelletier, the Canadian-born CEO and Chairman of the Board of Mack Trucks, a legend of his own, having worked his way up from the shop floor to run the company. The Strausses took Pelletier to see the gymnasts training in their borrowed space, then an upstairs floor of the Allentown Symphony Hall, and asked if he would help them raise money for a real gym.

Pelletier, moved and impressed, rallied support from across Allentown. The dream was to build a facility as safe, modern, and exciting as the one the Strausses had seen on a trip to Moscow shortly before the 1980 Olympics. There they saw their first foam-filled “pit,” into which gymnasts could safely fall from heights.

Allentown pitched in. Picture Thanksgiving weekend, 1981: A fleet of Allentown’s Mack trucks, filled with leftover foam padding from the airplane seats that Mack also produced, pulls up to the almost-finished Parkettes building. Two hundred town volunteers are waiting and armed with their electric kitchen knives to unload the foam and cut it up into small chunks for bedding for the pits. Other townspeople show up to install sub-flooring beneath the vaulting tracks and under the mats, put in telephones, or do whatever skills they possessed could do. Allentown built itself a gym that would become a world-class training facility.

I visited the gym on a hot late-August Monday morning, the first day of the fall season for the elite girls’ team. It was, in the favorite and in this rare case appropriate term of the gymnast-girls generation, awesome. The girls, ranging in age from about 9 to 17 years old, are the Parkettes’ best of the best. They mostly come from the surrounding Lehigh Valley region, although some from as far away as Delaware or New Jersey. The Parkettes is not a residential program; parents will drive the girls to practice every day, some staying to telecommute during the practice hours from laptops in the upstairs room that the club provides for them. Then they drive back home at the end of the practice and start all over again the next day. I imagine there is some studying going on during those commutes; all the girls are home-schooled, an experimental idea that the club rolled out in 2000, when it became clear that the highly-motivated gymnasts were burning themselves out trying to keep up with five or six hours of practice piled onto conventional school life. It has worked.

I’ve never been to an elite-training facility before or seen a gymnastics performance in person. Several things struck me while I watched the morning practice, both about the culture of the gym and the presentation of the girls:

The club. The Parkettes boasts the flashiest list of achievements: Olympians, national champions, world gymnasts, and full-ride scholarships to big-name universities. And yet, while the trophies, plaques, and banners are displayed proudly enough to inspire the up-and-coming gymnasts (and their parents), my eye was taken with a homegrown casualness of the place. It is a little messy, although several people told me it was clean-up season. And the practice space, while perfectly shipshape and strictly tended, also showed signs of modesty around its edges: carpets that needed replacing, a toilet that wasn’t working, hallways a-clutter with tables of trophies, photos, and lost items. To me, it looked like a very busy, very homey kind of place. There is also a room-for-all sense about the club, with its recreation-level programs, an adult program, and a special-needs program, which has sent gymnasts to the Special Olympics. The Parkettes also has a successful program for boys, but it is considerably smaller than the girls’ program. During my visit, only the girls were training.

The gymnasts. I watched the girls, even the youngest at about 9-years-old, carry themselves with laser-like focus on the floor, which spilled over to a beyond-their-years maturity off the floor. If you planted this group of girls next to a randomly selected group of others their age at a mall or in an airport and compared their composure, I bet lunch that you would agree with me. I watched every age group listen hard to their coaches, take direction, request clarifications, and stand straight taking criticism. While the gymnasts are clearly used to having outside observers and to behaving properly toward them, I stayed long enough to have broken down their guard and blended into the background.

Much of this gym-sense, you have to guess, is a reflection of the culture that Donna and Bill Strauss have created. I admit that before walking through the Parkettes door that morning, I steeled myself for the likes of Bela and Marta Karolyi, who make my stomach churn, even just watching them on TV. So, I was surprised at the down-toned, unwound demeanor of Donna Strauss. When I owned up to my preconceptions, Donna admitted back that their manner has evolved over the years. At the beginning, the model was “mean and ugly” as Donna puts it, “we thought that was what you do.” But they grew to see it doesn’t have to work that way, and they have moved toward a different style.

Realistically, of course, you can’t expect that everything is always so peachy. I was visiting during an off-time of the year, and Donna said understatedly, “It can get more serious.” Indeed, the script of the CNN documentary called Achieving the Perfect 10 featuring the Parkettes reads like a different and much tougher, more ruthless picture than what I saw that morning. The documentary was controversial, raising voices in protest from the coaches and some gymnasts that it was not representative of the culture of the gym. I did a quick search through the archives of Allentown Morning Call, which produced fewer stories of tension than I would have expected: the resignation of a coach and three assistants (1988), some internal bickering among parents (1988), and an (unsuccessful) lawsuit over an elbow break (1989).

We’ve all witnessed or participated in the glory and the heartbreak of sports. The gymnasts learn to accept success as well as defeat, says Strauss. Their club does, as well. The Parkettes lost a winner among their ranks this year when their current superstar, the world-ranked number one Elizabeth (Ebee) Price, chose to enroll at Stanford this fall instead of deferring to compete for a presumed spot at the World Championships in China at the end of the year. It would likely have brought that glory to herself and her club. They hated to lose her. But Strauss, who has been around for a long time now, says sanguinely, “The decision had to come from Ebee, and Ebee makes good decisions.”

So, how do the Parkettes play in Allentown today? You can hear the nostalgia in Donna Strauss’s voice as she reflects on Allentown in its boom times. “It was a vibrant and strong city,” she says, describing that coaches from visiting teams would come to town a day early just to a shop at the flagship Hess’s department store. “We’re still a heartbeat of the town,” Strauss says, “But these days, Allentown is not the same.” However, if the anchor of Allentown’s re-development dream, downtown’s just-opened 10,000 person PPL Center, regenerates life the way all are betting, the Parkettes hope to enjoy the spillover, too, with more recognition and more involvement. The new arena isn’t big enough to hold a blowout competition, which takes two huge floors—one for performance and one for warm-up—but perhaps it could work for smaller meets, says Strauss.

And if, God forbid, the economic dream (which John Tierney writes about for this series here) doesn’t work out for Allentown, the Parkettes can probably take the weather. Although Bethlehem Steel closed, Hess’s Department store shuttered, Mack Truck company was sold, Strauss says, “We survived. We stayed alive.” And as Ebee Price, the most recent superstar Parkette, nailed it in her farewell speech before heading to Stanford: “Once a Parkette, always a Parkette.”

Watch a Parkettes Training Montage here.