I visited many resettlement centers for refugees and immigrants across the country over the last three-and-a-half years. I also visited other support institutions, plus many schools with large populations of refugee and immigrant children; and I spent time with refugee and immigrant families, from the newly-arrived to the well-settled, in their own homes.

After the presidential election a few weeks ago, I called many of the contacts I had made in four of the towns I visited to get a sense of how their communities were reacting and responding to the election results. What the towns have in common is a sizable population of refugees and immigrants. Where they differ is in their political leanings. Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and Dodge City, Kansas, are in strong Trump-supporting Republican areas. Burlington, Vermont, and the city of Erie, Pennsylvania, went for Clinton.

I also spoke with Stacie Blake, a representative for the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants , or USCRI, who is in close touch with the group’s field offices around the United States.

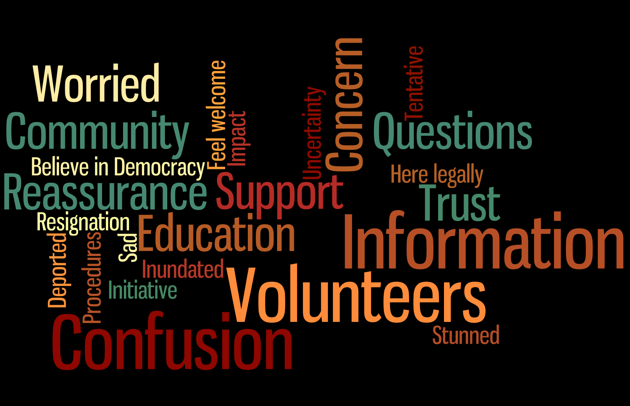

The reports from the people who work on the front lines with refugees and immigrants were remarkably similar, despite the political differences in the towns. Here is a word cloud of the most commonly used words and phrases that I heard in my interviews; they tell the story in a snapshot. Many people chose the same words to describe sentiments that prevailed post-election in their towns, and many outlined the same kinds of activities that residents were undertaking.

The sentiments: Worried, confused, concerned, tentative, sad, stunned.

On one end of the spectrum, Paul Jericho, the Associate Director for Programs at the Multicultural Community Resource Center in Erie, said the mood is tentative, and “There is no hysteria.” Similarly Dylanna Jackson, who runs the USCRI field office in Erie, reported her clients saying (poignantly to my ear) that they have “confidence in our system; they believe in our democracy.” Their anxieties, she said are less about themselves and more about their families who they hoped might also have a chance to come to the United States. I heard the same story of worries from Burlington.

True Tender and Hai Blu, refugees from Burma resettled in Burlington (Deborah Fallows)

True Tender and Hai Blu, refugees from Burma resettled in Burlington (Deborah Fallows)Similarly, from Dodge City, Assistant Principal Mike Martinez reported no overwhelming sense of urgency at Dodge City High School, and he told me that election news represents a learning opportunity for the students.

On the other end of the spectrum, Robert Vinton, who runs the broad-reaching Migrant Education Program in Dodge City, reports that many in the vast community he serves are “stunned,” and the reality of what has happened is “slowly beginning to creep in.”

The action on the ground: Information, education. Support, reassurance. Volunteers, volunteers, volunteers.

The residents of the towns with refugees are turning out immediately and in large numbers. In Burlington, Amila Merdzanovic of the USCRI field office there said they were inundated with calls and offers of support, and that 115 people showed up on their doorstep for a volunteer orientation. In Erie, Dylanna Jackson told me that people were calling to ask how they could help, with comments like, “I have to make the refugees feel welcome.”

In Dodge City, Robert Vinton consulted with his staff and decided to hold an immigration forum, open to the entire community, possibly including lawyers, to calm people down, inform them of what they know, and to offer support. He told me that they do this especially on behalf of the children. “They hear half-truths, and they don’t know how to handle it,” he told me.

Similarly, Jackson said they immediately took initiative with their clients—some of whom I visited last summer, just weeks after they arrived from Syria via a three-year wait and vetting process in Jordan—to answer their questions, help them feel better, and reassure them that they are in a good community.

Stacie Blake of the USCRI reported on her meetings with groups of refugees in North Carolina, to give them information, inform them of procedures, and assure them they would continue keeping them informed if situations change. Blake said their efforts are to keep information flowing, build communication channels, and sustain trust. What does this mean person by person? One Iraqi woman told Blake, “If they decide to send me back to my country, I’ll be grateful for the many kindnesses extended to me and my family.” And a Congolese man asked, “So when they put me in jail, will there be a number I can call?”

From Sioux Falls, Emily Johnson, who teaches a government class for English Language Learners at Lincoln High School told me her students came to school the day after the election with various emotions. Here’s how she handled the day:

I emphasized that checks/balances and limited government (principles we had spent a lot of time discussing) would keep one person from gaining too much control. Additionally, I emphasized that not everyone that voted for him believes in the rhetoric that he perpetuated throughout his campaign. They realized that now more than ever to we have to come together and respect one another.

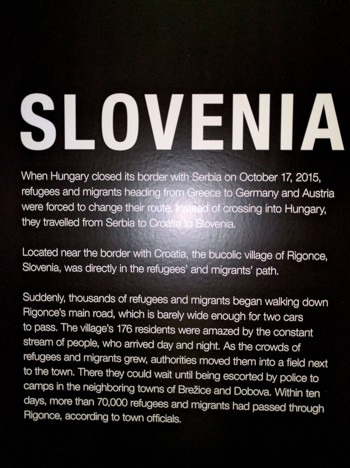

The Newseum in Washington, D.C., is currently hosting an exhibit of photographs called Refugee. It features photographs of refugees from around the world by five renowned photographers. The images are stunning, and quickly take you beyond the words we too often hear, which lose their impact through familiarity. Sentences like: “Reports are that South Sudan is on the verge of catastrophic collapse,” or “A boat carrying over 200 refugees has capsized in the Mediterranean.”

The Slovenia photos at the Newseum (Deborah Fallows)

The Slovenia photos at the Newseum (Deborah Fallows)One wall of photos particularly struck me. The collection was labeled “Slovenia.” I immediately thought of the only Slovenian I know—immigrant Melania Trump—and recalled some of the few words I have ever heard her say, in Philadelphia last summer: “Our culture has gotten too mean and too rough.” She was referring to cyberbullying, but it took no stretch of imagination to extend that sentiment to many other aspects of the culture, including how we talk about and treat each other.

So here is a place that immigrant Melania Trump might start. Anyone, especially she, could look at the exhibit and think, “There but for the grace of God…” She alone will soon be in a unique position to address the immigrant and refugee situation in the U.S. and to influence policy and urge society to be gentler and nicer, or to at least try.