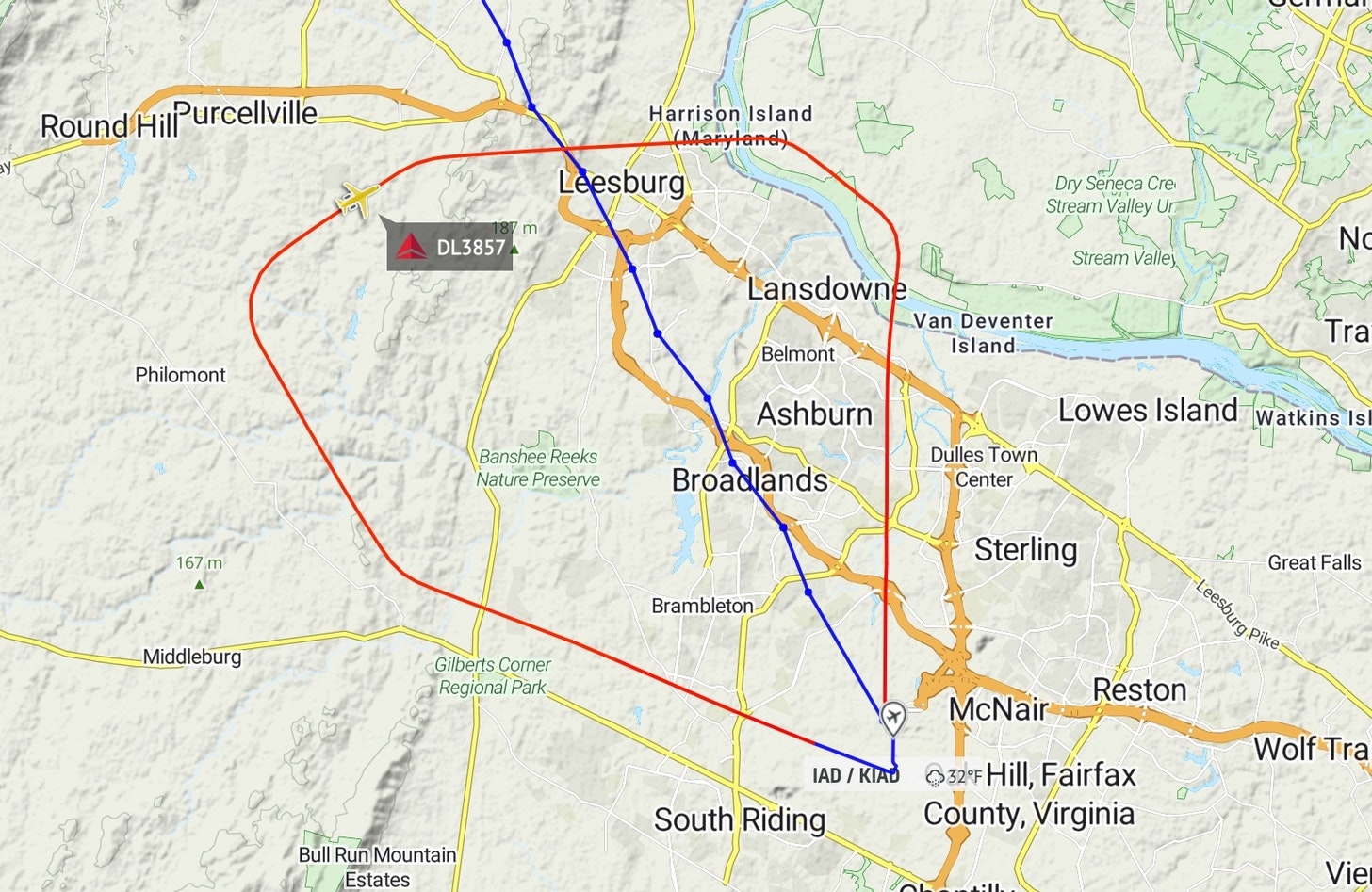

We took off from KGAI — the Montgomery County Airpark, our home airport outside Washington DC — early on a Friday afternoon, with big plans to look for the fall foliage en route to Eastport, Maine. The flight would be about 3 1/2 hours, even less if the expected strong tailwinds prevailed. [Above: Sunrise over Campobello Island, once we got to Eastport.]

We were climbing initially to 2500 feet, which I think of as the Norman Rockwell altitude. If you look down, you can spot yellow school buses stopping in front of white picket fences and see smoke curling out of chimneys. Just after we took off I heard Jim, my husband and pilot, say “Damn,” before I noticed the small “no communications” light on one of the electronic screens. This was a big word from a mild-mannered guy, but he immediately reassured me with, “Well, the worst that can happen is that we turn right around and try to rent or borrow a plane.”

In a moment, the “traffic sensor failed” light came on, identifying the problem. Even I knew this wasn’t really important; the traffic sensor detects nearby airplanes and displays them on an animated screen, along with their altitude and direction. It is a bonus rather than a necessity for flight safety. The most amazing part of the system to me is the loud, metallic, electronic voice that warns “TRAFFIC! TRAFFIC!” when another plane is near you. (Technically, or so I’m told by Jim, this is when the plane is within 1000 feet above or below our altitude, and 2 miles horizontally.) I think the voice must be optimally designed for pitch, stress, amplitude and general surprise value. I don’t like it, but that is probably the point.

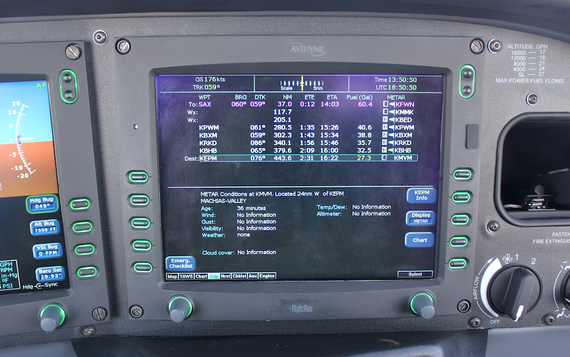

This is the screen that should show the traffic sensor. If you look hard you can see the little yellow indicator of “traffic FAIL” on the middle left of the right-hand screen.

Requesting “flight following” from the air traffic controllers (ATC) would substitute for the sensor system, which we did. Along the way, the ATC would periodically call us with something like “435 Sierra Romeo. (our call number) Traffic. 3 o’clock. One mile. Southbound, a G4 at 4000 feet.” We would look for the plane and inform the ATC “in sight” when we spotted it. Jim then stated a fact that I already knew: “Obviously, I’m gonna be watching this like a hawk.”

The leaves were still very green over Maryland; they were turning a mild yellowy-brown over Pennsylvania. The had barely even changed over one of my favorite flyover markers, the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, which sits proudly on a bluff over the Hudson with its expansive emerald green sports fields and marching grounds.

About that time, Jim mentioned he was looking for the updated weather report from the eastern Maine area, which was supposed to be clearing during our flight but was overdue on its hourly refresh. He played around with a few dials. I was still looking for leaves when he pointed out the major screen, the one showing all the gauges and important stuff like altitude and airspeed, began flickering. That was occasional. Then the flicker turned to longer flutters. Then it would go blank for seconds at a time. I could see the redundant manual dials were normal, and Jim said, “We’re fine; this is exactly why I did all that extra training during the spring. That’s why I was doing those simulated-panel-failure drills, with all the screens turned off.”

You won’t be surprised to hear that we decided to make a precautionary landing in Portland, the closest big airport (as Jim has previously described). It seemed beyond foolish to keep flying an extra hour north to the Eastport airport, which has no tower, no weather station, and no mechanics or repair shops. Jim told the controller that we were “changing destination because of non-emergency equipment problems,” a phrase I hadn’t heard before. He also requested a change from “Visual Flight Rules,” under which we flew whatever course we chose, to an Instrument Flight Rules plan, in which ATC would guide us to the destination. The ATC responded without a breath’s delay. “November 435SR is cleared to the Portland airport via direct, maintain 3,000 feet. Let us know if you require assistance.”

We landed in Portland, and stayed overnight with friends we had been long trying to visit. Through the magic that Jim described, we were on our way north to Down East Maine by noon.

That geographic nomenclature – Down East – was puzzling to me. I could understand the East, since Maine really sweeps out there into the Atlantic Ocean. The Down, I learned, apparently dates back to the olden days, when prevailing winds sent ships from Boston sailing downwind (hence down) to head north along the coast of Maine. Or maybe it’s some other reason.

We flew over the upscale enclaves of Mount Desert Island, and Bar Harbor, and many small private islands inhabited by either the wealthy or the reclusive—or sometimes one and the same. We swung around over Campobello and other Canadian islands for our landing to the west at Eastport, with its charm offensive of church steeples and clapboard houses. As we came in on our final approach, only a few hundred feed above the ground, a big green lawn-mowing tractor pulled out onto the runway. That was a surprise! So we “went around,” climbing back to 1000 feet above ground (and ocean) and setting up for another approach, by which time the tractor had spotted us and pulled off the runway.

The small airport was deserted. We were unloading and heading for a red Honda in the parking lot. The amazing Linda Godfrey, who is one of the dynamic forces for change in Eastport, had picked up the ball when she got word we were coming for a visit, and anticipated needs I didn’t even know we would have: “There are no car rentals here. I’ll find you one to use.”

Then a car drove up. “I heard you coming in,” greeted Captain Bob Peacock, one of two pilot boat captains who guides the enormous cargo ships into the deepwater Estes Head pier at Eastport. Amazing that he found us, I thought. We were one day and one detour late. This proved to be the first of about a dozen times we ran into Bob Peacock during the next several days. And also his friend Dean, and also Linda Godfrey, and many other people of Eastport who were all out and about on the streets. They seemed to have an uncanny anticipation of just what we would need and when we would need it. Cap’n Bob, as I fondly began to think of him, directed us to town (turn right and follow the road about a mile to the water) and said he would catch up with us later.

It all felt comfortable and familiar to me. I grew up in a small town in the midwest, on the Great Lakes. Everyone knew everyone. Kids didn’t have playdates; we just showed up at a friend’s house or at the corner lot to play. And parents always knew where to find us.

The next morning, Sunday, I got up and dressed early. I had a feeling I should be ready for whatever might happen. Sure enough, Cap’n Bob showed up at the back sliding glass door. “Hope it’s OK, “ he said, “The front door was locked.” Yeah, I thought to myself, I probably didn’t need to lock that door. Cap’n Bob began telling yarns – true ones – of the stories and characters of Eastport. Stories of Eastport rebuilding – in industry, in commerce, in architecture, in culture, and in spirit, which had been bruised and buffeted by decline, disappointments, and broken deals, but which was poised for a comeback.

We were already learning the first lessons of Eastport. It is a town that is very far away from the rest of the US; it is tiny; and it is surrounded by cold, deep water. Eastport residents turn those givens around to be wholly positive: Eastport, they describe, is close to the rest of the world, commands the engagement of all who live there, and understands the promise of the water.