A device, shown in a company video from the Ocean Renewable Power Company, or ORPC, shows the installation of a gigantic piece of equipment that I saw while visiting the small town of Eastport, Maine. Eastport, as we’ve suggested before, has been harder-hit than most other places we have visited, and is now in the process of placing its bets on a variety of prospects for economic revival, rather than being able to look back with satisfaction on big strategic choices that have already paid off.

One of those bets that is most astonishing, in its scale and in the long-term nature of its commitment, is ORPC’s attempt to create workable turbines to draw on the vast tidal energy of the adjoining waters. I am (alas! everything about being a writer is great, except for the having-to-write part) in the middle of writing an actual article about Eastport for our next issue, which will say more about ORPC and some of the other things we have learned from this little town. But as a place holder, before too much more time passes, I wanted to invite your attention to a project that would seem ambitious for Seattle or Los Angeles but happens to be based in a struggling town of 1300 people.

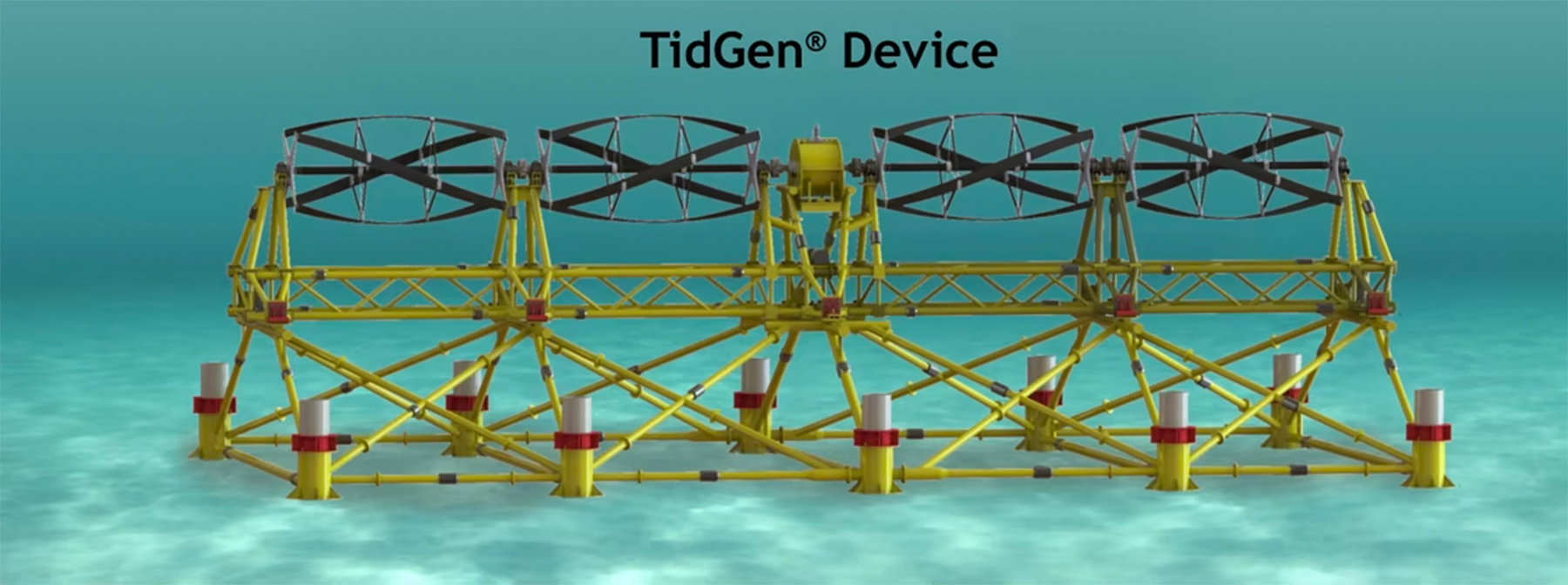

You can see a video from Solid Works, a 3D-CAD design company that has been using its computerized models to simulate the stresses on the turbine—and its generating potential.

And a raft of other explanatory videos at an ORPC site here. For now I’ll mention one comment that stayed with us, from ORPC’s Bob Lewis, an Eastport local who has been with the company since nearly its start.

As my wife and I walked through the company’s office in downtown Eastport, he showed us the series of more-and-more refined-looking helical turbines, with elegantly curving blades made of composites or wood.

As we saw the succession, I couldn’t help thinking of a similar display I had seen a week earlier in the otherwise completely dissimilar Qualcomm company in San Diego. Qualcomm is an international tech powerhouse with more than 25,000 employees; ORPC is just trying to get going; but there was the same pride in the Qualcomm “museum” in showing the progression from the earliest footlocker-sized mobile communication systems to today’s tiny, ubiquitous mobile devices. I thought of the comparison when Bob Lewis said this:

“One of the good things about this area,” he said, “is that the resource is so robust”—which he meant that the tides were so enormously powerful. “If our kits can hold together here and, even in their crude form, generate electricity, they can stimulate the development of the industry everywhere.

“We like to think that we are the Kitty Hawk of hydrokinetic power. Like the Wright Brothers team—I don’t know that they could envision today’s Boeing and Airbus and composite aircraft and whatnot. We are taking this innovation and trying to stimulate the imagination of people around this area, and elsewhere, to realize this potential.

“I am hoping for someone in their garage right now is tinkering with a better model. What I am hoping is that if I am so fortunate as to come back in 20 years, people will look at these models and say, That really worked? That’s our goal.”

Now, back to article-writing. Below, the way the turbine support looked last week when it was hauled out of the ocean for a scheduled inspection, and below that, a company drawing of how it looks underwater.