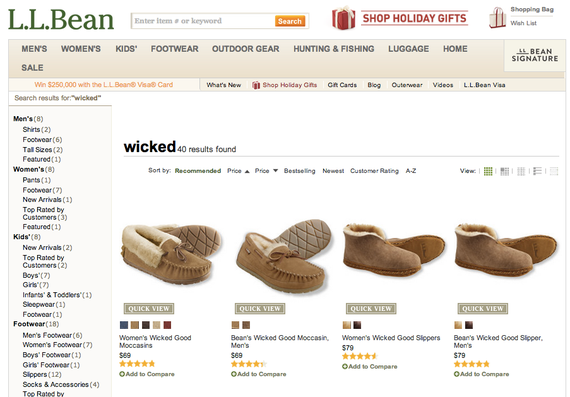

I always associate the word “wicked” with the Maine icon L.L.Bean. For good reason: do you know that if you search on the L.L.Bean website for “wicked” that you will get 40 returns? A lot of them describe slippers that are “wicked good,” or long underwear and throws that are “wicked warm” and “wicked plush,” and one “wicked tough” pair of chaps. Wicked is a great marketing word.

And of course there is Boston’s “wicked,” as captured in the famous “My boy is wicked smart” scene with Ben Affleck and Matt Damon in Good Will Hunting. It comes at the end of this clip. But let’s stay in Maine for a minute.

The L.L.Bean use of wicked isn’t the usual “evil” or even the “mischievous” wicked. It is a different wicked, which I figured must be a regionalism, and which the newly-completed Dictionary of American Regional English confirms is a New Englandism, mostly Maine and Massachusetts. I never imagined that people used the L.L.Bean wicked colloquially, or without intentional affectation.

Wrong! I wasn’t in Eastport, Maine, for a day before I heard it. Something like, “The winters here can be wicked cold!” At first, I wondered if this wicked was perhaps deliberately delivered for my benefit as an outsider, or “person from away” as I would certainly be called. By the third time I heard it, I knew it was standard speech. The people of Eastport told me it means “very,” a very, very intense “very”.

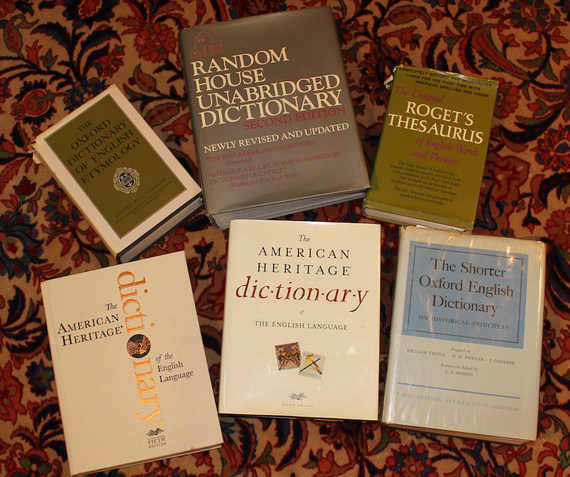

I decided to do a little research. I hauled out 5 of my dictionaries, all 11,580 pages and 42.5 pounds of them. The SHORTER Oxford English Dictionary weighs over 9 pounds itself and is 2515 pages long. I have both the 4th and 5th editions of The American Heritage Dictionary (full disclosure: my husband, Jim, is on the usage panel for this dictionary). Then there is the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, the Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, and a Roget’s Thesaurus, thrown in for good measure.

So what about wicked? The etymology looks pretty straightforward. They all say wicked comes from Old English (about the 5th – late 11th centuries) “wicca,” meaning wizard and probably also the feminine form “wicce,” meaning witch. OK, we start with wizards and witches. By Middle English (about the 12th – 15th centuries), it had taken the form wikke or wikked, and had a few more spellings like wicke and wicked. Spelling didn’t count for much back then. It was used as an adjective, meaning “bad,” by the 13th century.

By a few centuries later, the number of meanings grew (a common shift) to include “mischievous” or “playfully malicious,” as in “such a wicked kitten.”

By today we’ve got wicked meaning several different shades of bad, and also meaning mischievous.

And we have added two versions of wicked as slang. There is wicked meaning something like “wonderful, great, masterful, with an edgy skillful craftiness,” as in “He blows a wicked trumpet,” or “He throws a wicked curveball.” And the late 20th century arrival, where wicked would mean “good,” or the opposite of its most popular meaning “bad” (which is another common shift) as in “That is a wicked song.” Four wickeds, all adjectives.

Now, the word has evolved to include the L.L.Bean “wicked warm” meaning – now an adverb, and now meaning “very,” a definition that has made it into some of the noble dictionaries.

Another evolution, I think, is that the “very” meaning of wicked is now also used in adjective form. As in “I’ve got a wicked hunger,” which, I think, means “very intense” rather than just a version of “bad.” This isn’t even in Wiktionary yet, and I don’t have a native-speaker sense of it nailed down, so I’ll tread lightly on that. Anyone?

The real gourmands have a little to say about the pronunciation of wicked. A displaced Mainer explains the subtle pronunciation:

The pronunciation of the word wicked is key to not being seen as a Maniac wannabe. The emphasis needs to be on the first syllable, and an almost imperceptible pause before the second syllable is usually used for emphasis. It sounds like “Wick’-id” This is especially important is describing things dear to a real Maniac’s heart. A trout that puts up a wicked good fight before you net it needs good emphasis on the wick syllable. A wicked good pass by the high school quarterback to get a key first down against the arch rival school needs to be done slowly for emphasis.

And from the mouths of the experts (via the kpredd13 YouTube channel).

Bringing this full circle, I have to wonder: could we mash up the wizards, add a pinball, substitute the wicked-meaning-masterful for “mean”, and end up with a more etymologically interesting version of Pinball Wizard from the rock opera Tommy?