We returned to Eastport, Maine, in late August, nearly three years after our first visit, when we had become smitten with the tiny town of 1,300 people. Eastport is officially a city, which may be technically correct, but that term sheds the sense of charm and intimacy that the term town bears, at least to my ear. And indeed, Eastport is charming and intimate. On the other hand, the word city seems to suit when you consider the many ways Eastport “punches above its weight,” as my husband Jim often remarks.

We have written about how much is happening in Eastport, and how everyone—yes, nearly everyone—pitches in to make it happen. For instance, after we attended a performance of The Glass Menagerie in 2013, we realized that the ticket taker was also the editor and publisher of the paper, the Quoddy Tides, and that the stage manager Jenie Smith was, by day, the barista at Dastardly Dick’s coffee shop. That’s not the half of it; we learned on this latest trip that the barista is also the nephrologist at the town’s clinic. And that she and her husband, Peter, the owners of Dastardly Dick’s, had just added their longtime dream, a dog kennel, to their portfolio of businesses.

This weekend is the 11th season of the highly-anticipated Pirate Festival. Eastport boasts a long list of celebrations, like the Salmon and Seafood Festival and New Year’s Eve Maple Leaf and Sardine drop. Eastport is counting on their festivals a lot this year, hoping to make up for some of the changes in tourism caused by a few unusual events: 16 feet of snow and the town’s municipal pier collapse during the winter of 2014-2015. The effects spilled over into a slowdown in cruise ship stops and some tourist activities.

More shops have opened up along Water Street since our last visit: one for pet supplies, a bakery, an ice cream shop, a restaurant, a salt shop, and more galleries. The hardware store, which has been in the same family for several generations, has a beautiful new front. The Commons, a mixed-use building including condo rentals with an incomparable view of Campobello Island (we stayed there; book early!) and local artisanry, is bustling. They also rent to Eat Local Eastport Coop, a produce and deli next door that has added local beer, even one called Atlantic, as Jim will attest.

The Tides Institute and Museum of Art (TIMA), which John Tierney first wrote about here, still anchors the foot of the street, and their campus has expanded around town to six buildings, including two churches, a veterans hall and a historic house, with more plans in the offing. They are transforming the 19th-century buildings into vibrant 21st-century studios and workspaces, exhibition, presentation, and performance spaces, administrative offices and housing for artists in residence.

Its Studioworks, which has been home to nine artists-in-residence this year, up from four a few years ago, serves as model of energy efficiency against the down-east winters with a wood-pellet boiler, radiant heating, and closed cell spray foam insulation.

During this visit, we dropped by to see three among the many many artists in Eastport.

On Water Street, we wandered in through the open-doors of Studioworks one morning to find the current artist-in-residence, Richelle Gribble, an outgoing native Southern Californian in her mid-20s, newly arrived for her one-month residency.

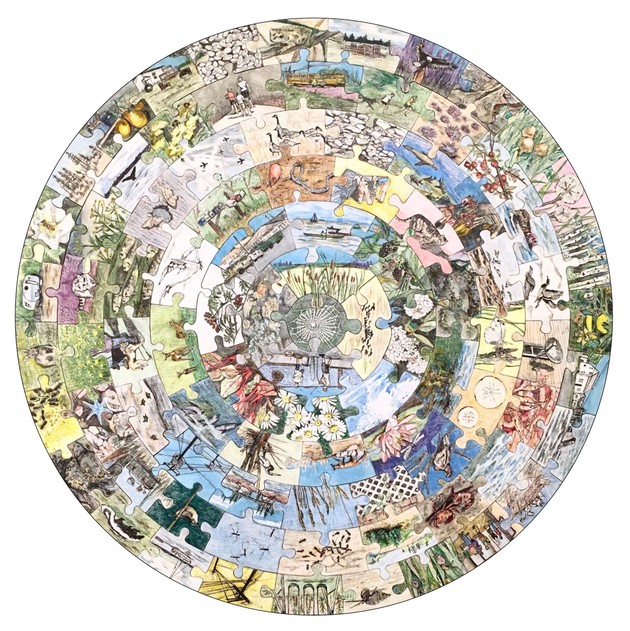

Richelle had hit the ground running and on this morning was busy adding pieces to a three-foot-diameter round puzzle, inspired by her eye on the ecosystems of Eastport. Each of the 91 wood pieces is a tiny drawing in graphite, ink, or colored pencil of something she has seen—bald eagles, whales, grasslands, oceans, forests, and local folks around town. All these images connect to form the spirit of Eastport, she describes.

In the back room, Richelle showed us the fruits of her findings from explorations around the water’s edge and hikes overland. She had laid out and categorized her treasures like an archaeologist, with netting, shells, bits of driftwood, plastic, and glass. As she emailed me, she paints these artifacts into “a series of 13 small round paintings of ecosystems. Each round painting will be linked together with string, creating a large network formation.”

Also along Water Street, I found photographer Don Dunbar, who has moved his gallery into the elegant 1882 Frontier National Bank building, next door to the library and across the street from the Tides Institute and Museum, also formerly a bank building.

Dunbar was a cartographer and lithographer during his three-years in the army. After his discharge, Dunbar bought a camera, partly to start building his credit score. He held a series of jobs around town, continuing to work at his new hobby. About 15 years ago, Dunbar began selling some of his photos and takes photos now for Eastport’s Quoddy Tides.

Dunbar’s passion for both photography and the nature he embraces is as striking as his photos. He sounds like a man who loves what he “does” not what he “is.”

Dunbar told me how a full workday might be sitting in a blind waiting for the wildlife to approach. All day. Even in winter. In Maine. In what struck me as a tone of humility, Dunbar said that he “takes” photos, rather than “makes” photos, the favored term of art usually heard from professional photographers. Dunbar told me that he is grateful that with his photography, he “makes enough to pay the bills.”

If you spend even only a few days in Eastport, you feel like Dunbar’s photographs are close to your experience there. The Head Harbour Light, the search for the rare right whales, the sighting of the playful minke (rhymes with pinkie) whales, dead-quiet Water Street at midnight. And those experiences we missed: the fishing boats in the winter fog, snow was so high it covered shop windows, an eye-to-eye stare down with the bald eagles.

Dunbar showed me around the gallery space, which like the old Eastport Savings Bank, now home to the TIMA, seems surprisingly small to imagine as a bank. The gallery takes up the main open room. He is about to clear out a back room to make way for his developing studio. Just as many things come full circle in Eastport, the back room was once the office of the bank’s manager, who was the father of Dunbar’s new wife, Kathleen.

Before we headed over to Campobello, Jim and I stopped by to see Hugh French, the director of TIMA. He handed us the key to the Free Will North Baptist Church, one of TIMA’s new acquisitions, and suggested we walk over to take a look at the new installation there. TIMA bought the church for performances, installations, presentations and extra studio space, and they have already hosted a baroque quartet concert, and a sound-sculpture-imagery installation by artist Janice Wright Cheney called Sardinia.

The current installation, called Undertow, was built for the space by artist Anna Hepler. She describes it as “the hull of an empty ship in… the nave of an empty church.” We prowled around the empty church, looked at the sculpture, made from Eastport’s recycled cardboard, from all angles—underneath from the pews, up above from the balcony, along the sides with the stained-glass windows.

Throughout our American Futures journey, we have been taking note of the impact of local art on the rebuilding of communities. We’ve also been listening to our friends at ArtPlace America, who support many of these projects, and have pointed us to several around the country, including the artists-in-residence in Eastport.

We’ve been trying to understand and to articulate what it means to have art taking root in the culture and economy of Eastport and other towns. A start for me is to imagine Eastport without its art. I was shocked at the vacuum this would create: gone the Tides Institute and Museum, gone the bustling galleries on Water Street, and the studios, and the openings, lectures, special installations, and the concerts and performances. Gone the meetings with the school-kids, which inspire them, and the visits from artists in residence, who bring outside energy into Eastport. Gone the photographic records of the natural beauty that even some Eastport residents have never seen in person. And perhaps most importantly, gone the participation and gatherings of Eastport’s people, who help create and share all this together.