This post is about a development that few people outside the state of Indiana have ever heard or read about, but that has implications for the country as a whole. It’s about a highly unusual approach to a highly familiar problem: the economic challenges of public schools. This news comes from America’s original “Middletown,” the midsize Indiana city of Muncie.

In the preceding installment about Muncie, I mentioned three aspects that surprised Deb and me—and that would have surprised most visitors, given their absence from the national press. One, discussed in the preceding report, was the ambitious geothermal-energy program designed to reduce nearly half the carbon footprint of the city’s dominant institution, the 22,000-student Ball State University.

The other two also involve Ball State’s interaction with Muncie—in a general way, and with a specific and highly unusual new step. This post is about those two moves.

The general step that Ball State has taken is to see itself as centrally involved in the economic and civic development of the city where it is based—rather than viewing Muncie from across the traditional town-gown divide. This is a trend that Deb and I have seen (as discussed here) in other places around the country. Last fall The New York Times had a related story in its business section titled “Universities Look to Strengthen the Places They Call Home.” That story featured East Coast illustrations: the University of Maryland’s role in College Park, outside Washington, D.C.; Drexel University’s role in Philadelphia; and Yale’s in New Haven.

At Ball State, this kind of “civic stewardship” in Muncie has been a central emphasis of the university president who took office two years ago, Geoffrey Mearns, who before arriving had been the president of Northern Kentucky University.

“When they interviewed me for this position, I said, ‘If you’re looking for someone to run a university, I am honored, but I already had a great job,’ ” Mearns told me when I first spoke with him last fall. Mearns grew up mainly in Ohio, studied English at Yale (where he was a track and cross-country star, eventually running a 2:16 marathon and qualifying for the 1984 Olympic trials), and practiced law for more than 15 years, including nine years as a federal prosecutor. He then shifted into university administration with a role at Cleveland State University.

“But I said that if they were interested in involving the university much more directly with the community, that would be very interesting to me, as well.” As a sign of sincerity: Soon after their arrival, Mearns and his wife, Jennifer, donated $100,000 for an endowment to sponsor Muncie Community Schools graduates who would become first-generation students at Ball State.

This kind of interaction would be a change for Muncie, where the university and the city had been for decades co-located but not deeply cooperative. As mentioned earlier, the sociologists Robert and Helen Lynd selected Muncie as the site for their famed Middletown study precisely because it was so clearly a midwestern “factory town” rather than a “college town.” But the shift toward involvement with Muncie is a basic part of Ball State’s current strategy.

“Our University’s future is affected by the vitality and vibrancy of Muncie,” Mearns said in a statement to the Indiana legislature early last year, a few months after he started at Ball State. “In short, our fortunes are linked.” The title of the current Ball State initiative is “Better Together.”

The idea of such a town-gown inevitably linkage is becoming more widespread. The specific implementation in Muncie is practically unique.

The axis of the linkage is the local public-school system, known as MCS, for Muncie Community Schools.

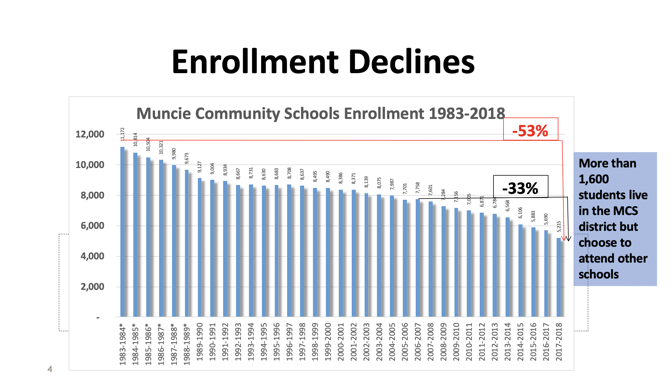

For decades, the schools had been a classic example of a distressed industrial area’s vicious cycle of decline. Over 35 years, the MCS enrollment fell by more than half. This chart, from a Ball State presentation on the future of the schools, shows the pattern.

Part of the change was from deindustrialization and a shrinking number of households with children in the area. But as the chart shows, about a third of students eligible to attend the community schools have chosen to go elsewhere: to private schools, religious schools, charter schools, or other options.

Since state funding for schools in Indiana depends heavily on enrolled-student head counts, the cycle of decline became self-accelerating. (Years ago, I wroteabout the effects of the same pattern in Michigan, with the Holland schools.) Fewer students means less money; less money means cutbacks, school closures, and fewer programs; cutbacks (etc.) drive students away from the schools; even fewer students means even less money.

My story about Holland involved a public-school system whose leaders were then navigating the way out of the cycle. The MCS leaders seemed to be navigating their way right over the cliff. Starting with the financial-crash year of 2008, the schools operated with heavy deficits, totaling more than $35 million in 11 years.

In early 2017, the system’s CFO resigned after news broke that some proceeds from a big school-bond issue had been used to cover operating deficits, rather than for repairs and investments (as reported by StateImpact Indiana here).

Schools were closed; teachers were laid off; academic-quality ratings fell. Finally, in December 2017, the state of Indiana declared the Muncie schools (like those in Gary) to be a “distressed political subdivision,” and put them under direct state-government control, through an emergency manager.

The following month, in January 2018, Geoffrey Mearns, then less than a year into his Ball State tenure, made a surprising proposal on Ball State’s behalf. He said that the university would assume responsibility for the city’s schools, transferring them from the state’s emergency manager, if the structure of the school board could be reconstituted. The announcement was enough of a surprise that, in initial news accounts, many officials said they couldn’t comment, because they hadn’t yet seen the plan. (For instance, from the first-day news in the Ball State Daily: “‘I was caught off guard because I had no idea the amendment [authorizing the switch] was in the works,’ said Rep. Sue Errington, D-Muncie. ‘I think [Ball State is] making a very nice offer. But it has been sprung on us.'”)

A plan like this—for a university to run the whole local school system—had never been tried in Indiana, or nearly anywhere else in the country. The closest and best-known parallel would be Boston University’s management of the Chelsea Public Schools in Boston, from the late 1980s to 2008. (An Indiana Public Radio show examined the lessons, plus similarities and differences). According to the chairman of the Board of Trustees at Ball State, the Muncie project was the first time a public university had assumed responsibility for local schools. (Boston University is private.)

The plan’s acceptance in Indiana was the result of extensive deliberations through the first half of 2018. These were deliberations by the state legislature, which agreed to turn over responsibility to Ball State; by the Ball State trustees, who agreed to accept responsibility; and by a wide variety of groups within the community that would be affected. The legislative and budgetary details are more complex than I can begin to present here. (If you’re interested, I commend to you: Indiana Public Radio in January 2018; Inside Higher Ed in March; and then the Muncie Star Press; Indiana Public Media; and the Muncie Journal in May. Links in these stories will lead you to more.)

“I was talking with a state senator about the plan,” Mearns told me in Muncie. “After listening for 15 minutes, he said, ‘Don’t do this; run away; stay as far away from that school system as you can.’ After another 15 minutes, he said, ‘You’re still crazy. But you have to do this.'”

How is it all working? In the spirit of “showing our homework,” I’ll say that Deb and I haven’t yet been inside the schools, and we will return to learn more. I am sure there are complaints and contradictions, as well as progress.

But from the outside, here are two aspects of the project so far that seem worth broader notice.

One is the systematic process of civic engagement that led to the selection of the new school board, whose seven members you see below:

The legislation authorizing the switch-over said that two of the appointments would be made by the Ball State president—but one from a list of three candidates proposed by the mayor, and the other from a three-candidate list proposed by the city council. The other five would be appointed by the Ball State trustees, from nominees proposed by the university president.

The university put out a public call for these nominations. It said it would be looking for diversity in race, gender, age, and working experience, and that priority would go to people actually living in town. It received 88 applications, the great majority from people living in Muncie. The university winnowed them down to a panel of 20 finalists, who answered questions at a two-hour public forum last June.

The seven members eventually chosen are: a special-ed teacher with school-age children, the YWCA’s executive director, a lawyer and former head of the Ball State University Foundation, a local banker, a Ball State official (who directed the geothermal-energy project mentioned before), a pastor, and a former state-court judge. Five men, two women; five white, two black; six of the seven attended Muncie Community Schools.

I met with board members for an hour last month in Muncie, and asked each of them why they’d decided to apply for this post. “I couldn’t not throw my hat into the ring, because the challenge is so important,” the lawyer, Mark Ervin, said. “If you have a chance to make a difference, you take it. You don’t have that many chances.” Brittany Bales, the special-ed teacher, had taken her young children out of the Muncie schools but brought them back. “It’s a mirage that it’s better somewhere else,” she said. “It’s more diverse and interesting within MCS.”

The other striking initial aspect of the project is the tangible local support it has generated. The new university-led school structure has raised more than $3 million in local donations to the schools, starting with $1 million each from two different Ball-family foundations and around $250,000 each from three local banks.

To emphasize the obvious for now: I don’t know how this project will pan out, and neither do the people pouring their effort and money into it. The former judge on the school board, James Williams, told me, “We have a long way to go, but we’re all pulling in the same direction. We’re still in crisis, but we’re making progress.”

But even while the outcome cannot be known, the inventiveness and effort seem worth notice outside Indiana. (As a local-media point: Every stage of this transition has been covered by the Indiana press, but as far as I can tell, the Ball State/MCS project has never appeared in national papers like The New York Times or The Washington Post.)

I thought of what I heard from Susana Rivera-Mills, who came to Ball State last year as its new provost. She and her husband, a concert musician, had been in Oregon when recruited to Muncie. She is originally from El Savaldaor; her husband, from the northern California coast—in both cases, very far from central Indiana. But “we felt the sense of life, the energy, the anticipation for something new,” she told me. “We couldn’t imagine not being part of what was going on.” With all normal allowances for boosterism I can still say: discussions like this gave me a different view of life in Middletown than I had before going there.

This is the fourth installment from the “vein of gold” road trip that Deb and I took along Indiana’s I-69 corridor last month, in the company of friends from New America–Indianapolis and Indiana Humanities. The previous installments are here: about Angola, about Fort Wayne, Part One about Muncie, and about the new Our Towns journey as a whole.

(“Road trip,” for a journey by small airplane? We’ll be back to airborne travel soon.)