The Andrew Heiskell Braille and Talking Book Library, a branch of the New York Public Library system, is in the Flatiron district of Manhattan. It looks like another storefront, opening onto a sidewalk with overhead construction scaffolding, like so many buildings in New York City these days.

I have visited many, many public libraries around the U.S., but I had never visited a braille library. So when Jim, my husband, and I happened to be in New York City in early June, I grabbed the chance and took Jim with me. We saw sighted and blind people entering—moms pushing strollers, younger people who looked like students, older people coming to bide their time. And we learned about yet another way in which modern libraries are serving their communities.

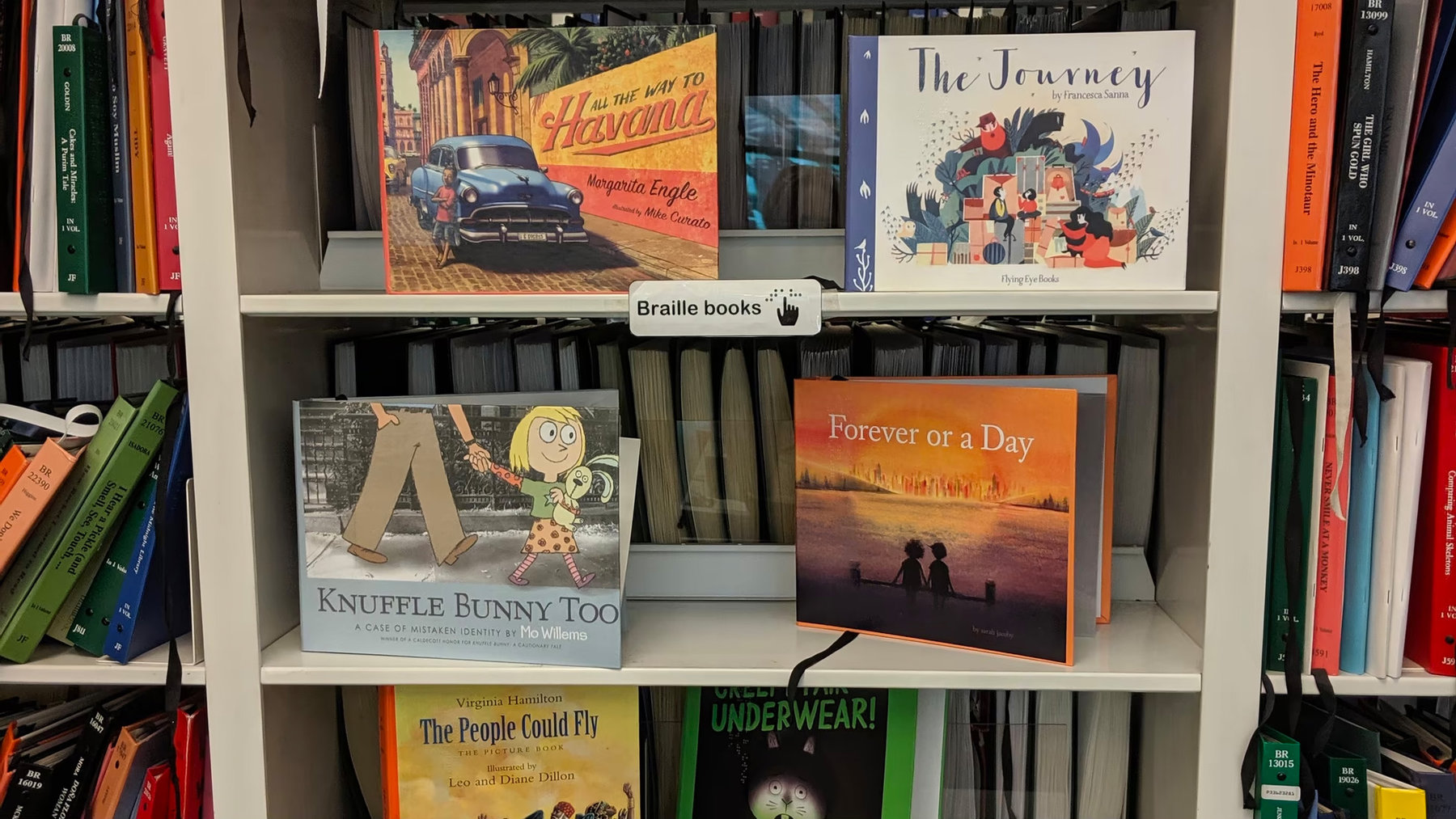

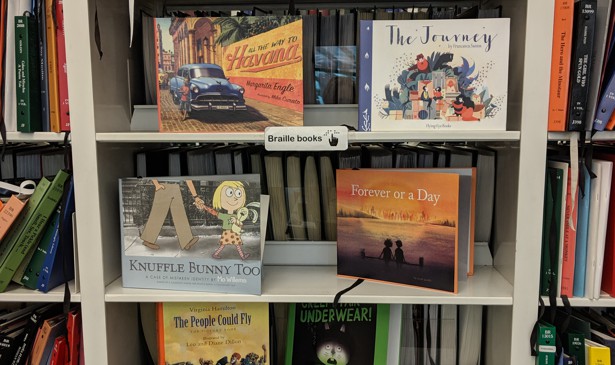

When you take the elevator to the second floor, you quickly see that this library has something very special. For starters, the library holds what is among the largest physical, browsable collections of braille books in the country, about 14,000 titles. Front and center, as is the case at most every other library I’ve visited, there is a children’s section. Braille books for children look just like the counterparts for sighted children, except the text is reproduced in braille, and sometimes the books include tactile features, like the furry fluff we all know from Pat the Bunny.

There are other ways to access books besides browsing and borrowing from the shelves at Heiskell. Through its membership in the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NLS), this library and its eligible users have access to additional physical braille books, downloadable digital braille books, books to listen to, plus subscriptions to many, many magazines from The Atlantic to Playboy. The NLS was established by an act of Congress in 1931, and operates under the Library of Congress.

As for physical braille books, the Heiskell currently mails them, with free returns via a mailing card that reads “free matter for the blind,” to over 10,000 patrons who live in the five boroughs of New York City plus Long Island. For its most voracious readers who would like a constant supply of books at the ready, there’s an easy answer. Readers can identify personal preferences—like thrillers, or books set in Italy, or historical fiction, and the library will send out huge stacks, as many as 40 books, whenever they are available.

And then there are books for listening. Talking Books is a program of the NLS, which records and distributes their collection of about 200,000 recorded books—also for free—to people with certified visual impairment. This includes not only blind people, but those visually impaired who find it hard to read; people with other disabilities, like Parkinson’s or MS, who have difficulty holding and manipulating books; or those with reading disorders like dyslexia.

Listeners can download the talking books through an app onto mobile devices or computers, or use a memory card that plugs into a special talking book player, which the Heiskell library also lends. The listening technology has come a long way in the last 90 years—starting with the 33 1/3 RPM records of the 1930s, followed by cassette tapes, then flash memory devices, and then apps to download content.

Altogether, the Heiskell circulates about 500,000 titles as braille books, Talking Books, and digital downloads annually.

The Heiskell, along with the NYPL system, is pushing beyond today’s opportunities—and limits—to develop new assistive technology and programming for the blind. Chancey Fleet, who is blind, coordinates the assistive technology program at the library. She talked to us with a combination of passion and reflection about her self-described role as catalyst, and as connector and amplifier. “I could go through life accepting the limits that inaccessible technologies create, but I’d rather go through life trying to help create solutions,” she told us when we visited with her; Jill Rothstein, the chief librarian of the Heiskell; and Bobby Sherwood, who works for the NYPL.

Chancey said she is using the privileges of her past (meaning mentors, training, and support in college and work) and the advantages of her current position (meaning accessibility to those with skills, expertise, creativity, and authority to make things happen) to help create and put new and useful technology into the hands of as many people as possible. And the goal of it all? What she said struck me as both the soaring and grounded purpose of the human experience: to offer people opportunity to express themselves and to explore the world.

Chancey demonstrated some of the technology for us. To convert text from a computer monitor to braille, she uses a small digital display unit, which has tiny pins that pop up and down to create the braille characters on the one-line, refreshable display. The unit can either read from a memory card, downloading books for example, or it can connect directly to a computer, smart phone, or tablet to enable real-time actions, like using email. She creates braille on the unit’s keyboard. The library has just announced a pilot program to loan similar “Braille Me” units to its patrons. Chancey also listens to talking books, often speeding up the delivery to 500 or 600 words per minute, compared with the normal talking speed on podcasts of about 150 or 160 words per minute.

As for programming, the ambitions of Chancey and her collaborators started small with their community of visually-impaired people, offering workshops to familiarize them with screen-reading tools and various apps. Then they went bigger by helping them to more easily access the visually-oriented world of coding. Then even bigger toward using tools to make spatial and tactile learning more accessible. The Dimensions project at the Heiskell offers training to use the hardware and software to design and create tactile maps, images, graphs, diagrams, actual objects, and other spatial information. Everything is free, and it is available to both visually-impaired and sighted people.

These technologies bring a perspective and experience to the blind that may be difficult for sighted people to appreciate. An embosser can print out a map of the five boroughs of the New York area, for example, where many Heiskell patrons live, showing in raised form the shapes of the boroughs and their relation to each other and the waterways around them. A 3D printer can replicate an object, maybe a dinosaur, that is scaled down to a size that makes sense when you can newly feel the entire object at once.

On the lower-tech end, there are many additional programs and experiences provided by the library: origami, a knitting club, tech coaching for Spanish speakers, video games, art classes, movie discussion groups with narrated descriptions, and workshops for high schoolers for prep for college tests and college class work. When their annual fair on community, culture, and technology outgrew the space at the Heiskell, they moved uptown to the bigger, grander main flagship library. At the fair they also publicize activities like beep ball (baseball with a beeping ball), ice climbing, and boulder climbing.

While much of what I learned about the Heiskell library is extraordinary, other aspects are exactly the same as at every other library. Everywhere, library users approach librarians with their important or sensitive questions. They trust librarians and the information they will impart. Those questions can tell a lot about a community. In Bend, Oregon, a few years ago, librarians told me that the most frequent questions from users were about how to meet house payments or their rent. In Charleston, West Virginia, people would frequently consider librarians as proxies for doctors, asking, for example, about suspicious moles. At the Heiskell library, different and sometimes poignant questions are posed: “Where can I buy a white cane?” and “How can I learn to type again?”